Enoch Boulton: An Unsung Hero of Art Deco Design

[an article supplied by

Desmond Guilfoyle -

who has a blog on articles

about the Fieldings Crown Devon factory.

This can be seen at

http://crown-devon.blogspot.com/

]

|

|

In 1929, newly appointed design and decorating manager, Enoch Boulton, former design chief at the Carlton Ware factory, oversaw the Devon Pottery’s bold incursion into Art Deco design. Boulton was originally apprenticed to Grimwades, and, as part of his apprenticeship, studied at the Burslem School of Art, the breeding ground of other Art Deco luminaries including Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper and Moira Forsyth. Enoch Boulton is only now beginning to be recognised by art pottery historians as a significant force behind the inception of one of the most original and creative periods of W & Rs history. According to accounts of conversations with Freda Boulton written by Ray Barker, Enoch obtained a position at the Wiltshaw & Robinson factory in around 1908, some time after the completion of his apprenticeship at Grimwades. After about thirteen years of working his way up to a senior design position, he replaced Horace Wain as Design Manager in the early 1920s when Horace moved to A.G.Harley-Jones & Co, the manufacturers of Wilton Ware. Boulton’s work was richly stylistic and colourful and was originally influenced by the Art Nouveau and Edwardian styles before it began to take on a discrete modernity of its own. A highly accomplished painter, Boulton is said to have created many of Carlton’s most collectible lines of the 1920s. The outstanding Tutankhamen ware (1924-27), celebrating Howard Carter’s discovery of the boy king’s tomb, and featuring gilt transfer prints of Egyptian themes with overglaze enamels on magnificent blue stippled grounds, is but one of his more notable contributions.

|

|

Influences on Boulton’s DesignsIt is believed that Boulton’s Carlton Ware Art Deco designs of the late 1920s were heavily influenced by the Exhibition des Arts Decoratifs in Paris in 1925. The British pottery industry was relatively tardy in introducing Art Deco design, and it wasn’t until around 1928 that Art Deco patterns from the design room of Wiltshaw & Robinson began to materialise on the Carlton Ware range. Some of the earliest Carlton Ware Art Deco patterns appeared on tea services, introduced during the Boulton era in around 1928. Within a couple of years of its cautious introduction, Art Deco ceramics design in Britain became more like a pastiche of the European Art Deco pastiche. Much of it can be seen as a somewhat belated expression of folk art for the masses that eventually captured the imagination of those with deeper pockets. This is not to denigrate the British efforts, but to demonstrate it’s essentially populist origins. No better illustration of this is the case of Clarice Cliff who became the “People’s Designer”, infusing vibrancy and freshness into a somewhat dull and dated British decorative art scene and adding much colour to the tables and living rooms of the working and middle classes. More than eight million pieces of her Bizarre ware alone were produced in the 1930s. |

|

|

|

|

Boulton Designs of the 1920sBoulton is said by the V & A Museum to have designed the Carlton Ware Jazz patterns that have been lauded as the quintessence of British Art Deco design. The pattern 3352 is represented in the museum’s pottery collection and is dated by the museum as c1921-30. There is, however, some discussion over whether Jazz is one of Boulton’s designs. If one is to date the design using the standard Carlton dating system of plus or minus 2 years on the first two digits of the pattern number, then Jazz would date between 1931-1935: a year after Boulton left Carlton Ware to join Crown Devon. However, there is no clear evidence that the rule of thumb dating system used for Carlton Ware is accurate beyond that of a highly generalised guide. By the end of the 1930s, Carlton Ware pattern numbers had reached 4500, thus opening up a minimum four year and a maximum seven year gap in the dating system. The system also doesn’t take into full consideration the lag between the creation of a design - design ideas could languish in the design room until it was propitious to use them - scheduling the pattern for production and production of the range itself. The ambiguity of dating throws into confusion the whole issue of attribution of designs to Boulton during the ‘changeover period’ to Crown Devon. |

|

|

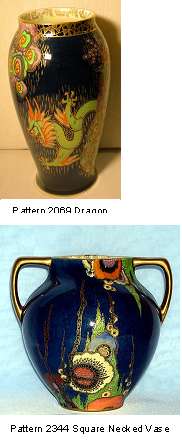

Further, in 1929, the Fieldings design portfolio was clearly jaded and woefully inadequate to meet the emerging popularity of the British version of Art Deco. Claris Cliff was already making her mark with her ‘Sliced Circle’, ‘Crocus’ and other patterns as early as 1927. There is strong evidence that Boulton was seen then as an accomplished contemporary Art Deco designer with a substantial portfolio and was lured to Crown Devon to upgrade its designs and shapes to meet the growing clamour for ‘folk art’ Art Deco. An upsurge of Art Deco designs ensued shortly after his appointment, thus cementing Boulton’s reputation as a populist Art Deco designer of note. Many other patterns, colours and shapes that Boulton is believed to have introduced are highly regarded by Art Deco historians and specialists, and his importance as a designer is reflected by the premium prices many of his mid to late1920s Carlton Ware designs fetch at auction houses in the world’s main auction centres. Boulton can be credited with having either created or overseen the introduction of a range of truly stunning patterns and designs. They include Jazz; Tutankhamen, fabulous Persian Temple designs; multicoloured Parrots; Dragons; Fairy or New Flies; Temple and Kingfisher designs. The highly collectible New Mikado and Chinaland designs were also released during the Boulton watch at Carlton Ware, as were New Stork and a host of other eye-catching shapes and patterns. An interesting sidelight to a number of the Boulton patterns is that they appeared on ‘historical’ body shapes, many of which were Chinese in origin. As raised earlier, any discussion about Enoch Boulton’s work must be partly based on conjecture, at least in the sense of pure historical inquiry. In attributing works to Boulton, the collector and expert alike must rely on oral history and other clues that point to the hand of this most modest of men. The records of W & R are far from complete and have not been examined exhaustively for definitive clues on the origins of various patterns and designs. Some important Carlton Ware records at the Stoke Library, for example, have been declared off limits to researchers and scholars and reserved for one or two individuals in an extremely curious arrangement that appears to be stifling efforts to uncover the truth. Fieldings lost many of its records in a devastating fire in 1951 and it’s highly unlikely that a complete history of the company, its people and its patterns will ever be established. Further, the claims and counterclaims about origins have not been fully tested for veracity. For example, the daughter of Horace Wain, Boulton’s predecessor, is reported to have said that Horace had a hand in the design of the Tutankhamen range, and yet Freda Boulton stated that Enoch took over as design chief at W & R in the very early twenties. Indeed, most of the written accounts also indicate that Horace had left the company in the early twenties, and it is, therefore, impossible to give credence to the above assertion. This is pointedly so, when the evidence shows that the Tutankhamen designs would not have been released until the mid twenties when the embargo on Tut’s tomb was lifted. |

||

Boulton at Crown DevonIn 1929, when Abraham Fielding was in the twilight years of his life, he began a talent search to fill the gap that would be left when he went into semi-retirement. Also, it becomes clear, when one reviews the Crown Devon output of the late twenties against emerging trends that Fieldings pattern books were dated and the company was somewhat unprepared to step into the new era of populist Art Deco ceramic design. The company was very active in introducing new lines, however many of its patterns still catered for Edwardian and even earlier aesthetics, which, it must be admitted, still continued to mirror the sensibilities of a large part of the British market. But Abraham Fielding could not have helped but notice the growing popularity of the Art Deco and modernist movements on the continent and similar stirrings in the United Kingdom. His choice to lure Enoch Boulton away from his major competitor, Carlton Ware, to take on the role of design chief at Crown Devon was a masterstroke. It helped create conditions for a unique combination of inspiration, motivation and expansionary zeal that positioned Fieldings to make the most of the ruinous economic circumstances of the time. Abraham died two years after Boulton’s recruitment, and his son Alec Ross took over the reins of the company. While regarded as an able manager, he was known to have his heart in matters other than the business. It was the younger ‘turks’ such as Reginald, representing the fourth generation of Fieldings in the firm, Enoch Boulton and Sales Manager, George Barker, who joined forces to bring new energy and commercial success to the company. Boulton’s arrival at the Devon Pottery coincided with the onset of the Great Depression. At this time, supply was outstripping demand, competition was cutthroat and many of the more prominent potteries were adopting defensive positions against the widening effects of the depression. Fieldings, on the other hand, took a contrarian and aggressive stance that offered the prize of increased market share. As Commercial Director, Reginald Fielding appears to have inherited Abraham’s mercantile spirit and was a keen advocate of expansion into other markets, particularly overseas. However, without the incredible design groundwork and revitalisation undertaken by Boulton from the time he joined the company, Fieldings would not have been in a position to take advantage of the opportunities the depression presented. Boulton and Barker, particularly, made a formidable team. Barker’s astute sense of what was selling and what could sell in the populist sector of the market worked symbiotically with Boulton’s design intelligence and artistic capabilities to bring about many of the best designs and shapes ever produced by the company. Soon after Boulton’s arrival at Crown Devon, the company’s back stamp was changed from a somewhat tired Edwardian logo to a modern Art Deco motif that, in hindsight, was a strong portent of what was to come. Interestingly, one of the actions Boulton took in the earlier stages of his role as design chief at Carlton Ware was to redesign its back stamp, again signalling the beginning of a new design story that ultimately changed the course of that company’s history. At the Devon Pottery, Boulton presided over an extraordinary upsurge in the development of contemporary decoration, overseeing a significant improvement in both quality and design. The results of this burst of activity were the subject of much trade comment. The Pottery Gazette of April 1st, 1932 recorded that, “Many wonderfully attractive lines of altogether fresh interest and above all at very popular prices are continuing to pour out of this source”. The gazette dates the beginning of Fielding’s renaissance as the summer of 1930, some months after Boulton joined the company, clearly establishing the link between Boulton’s appointment and the dramatic increase in design and production activity. The Gazette notes that an intensive modelling campaign that began in June 1930 and which, “First revealed itself in the samples which were produced (June 1930) for the trade of the Christmas before last is being pursued as actively as ever and this is being accompanied by a corresponding activity in the matter of new decorations.” This was news precisely because many other British potteries were still laying low in the face of the depression, Carlton Ware, for example, closing its Birks, Rawlins fine bone china operation in early 1933 for fear that it would bleed the parent company dry.

|

|

|

|

|

With Fieldings taking a contrarian stand in the face of the harsh economic circumstances of the time, Boulton engaged in a frenzy of design activity and experimentation. His understanding of the roots of Art Deco populism allowed him to merge modernism with the extravagance of the Sybarites, mixing modernist shapes with sybaritic patterns to outstanding effect. A classic example of his ability to merge these two diametrically opposed styles was that of taking a modernist star shaped vase and decorating it with an exquisitely enamelled sybaritic pattern of dragons. Without shame, he also decorated traditional pots with stunning deco designs. Throughout the gloomiest years of the depression, Fieldings was notable for its persistence in introducting new and progressive designs, shapes and novelties. A confluence of economic imperatives, commercial courage and design excellence produced what many consider to be Fielding’s most fertile design period (1930-39). Given ample creative latitude by the Fieldings management, Boulton produced designs and shapes that were not only highly successful in the commercial sense, but also of high decorative and aesthetic merit. Boulton upped the ante at Crown Devon with the production of exquisite Art Deco ornamental ware, of which the Orient design is one the most striking and original, and the creation of Art Deco and geometric tableware and other fancies. Another of Boulton’s accomplishments was the Mattajade ground, which, combined with a rich array of sybaritic designs, is one of the most collectible of all Crown Devon patterns today. The matt feel of Mattajade was created to take advantage of the awakening interest in Art Deco design and matt effects in the higher end of the market and it hit its mark perfectly.

|

|

|

A further Boulton success was the Amazine ground. A matt, azure tone emulating the lightest of turquoise colouring, it provided an ideal canvass upon which to create enamelled designs, amongst which were the Swallows and exotic bird patterns. Fieldings were acknowledged as being the first pottery in the country to produce matt glazes of this particular type and were lauded in trade publications at the time. The Mattita, Mattasung and Mattatone series are further examples of Boulton’s remarkable output. Boulton was especially prodigious in producing designs and shapes for the Mattita range, from quirky novelties to modernistic shapes hosting dramatic Art Deco designs Enoch is also responsible for Crown Devon’s highly popular musical novelties, the first of which he painted and gifted to his wife Freda. In fact, he can be seen as a trailblazer in the design and manufacturer of musical novelties in the United Kingdom. His Daisy Bell musical jug, incidentally, became a favoured possession of the young Princess Elizabeth.

|

|

|

||

|

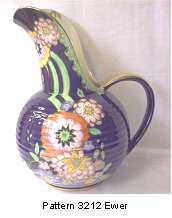

Fielding’s broad foray into the embossed wares genre was directed by Boulton and he expanded extensively the company’s range of embossed salad, tableware and table novelties. Boulton had designed a range of embossed wares for W & R and was well versed in the latent design potential of this genre. Significant amongst Boulton’s achievements was the move away from ‘historical’ shapes and bodies that reflected earlier English, European and Chinese styes. He introduced an extensive range of geometric forms and decorations including ribbed bodies, mouldings that gave an asymmetrical look, embossing and a myriad of other shapes that complimented the stylised patterns appearing on the wares. Boulton also introduced contemporary decorating techniques that included tube lining, exquisite overglaze enamelling, flatbrush applications using vivid enamels, boldly coloured looser form designs (of which the Cretian pattern is a stunning example) and a cluster of other methods that were gaining currency at the time. It is impossible to determine who introduced these new decorating methods into British ceramic decoration, but it is very clear that Boulton was amongst the ‘first wave’ of British designers who drew inspiration from what was happening on the continent and copied, modified and adapted the art pottery decorating trends of Europe, creating innovations of their own in the process. His importation of German matt glaze ideas to create Mattajade is a classic example of the transformation of foreign practices to appeal to local sensibilities.

|

|

|

Enoch Boulton was made a Director of Fieldings in 1949. His second wife Freda was a paintress with the company from 1934 until they both left the company in 1950. Enoch joined Coalport in 1950 as Commercial Director and remained with that company until his retirement. He passed away in 1972 and his widow Freda outlined him by more than twenty years. Boulton is yet to be awarded the status he deserves, that of standing alongside a handful of influential and significant British designer/decorators who exerted an enormous influence over populist design in the twentieth century. He was not an individualist of the likes of a Daisy Makeig-Jones and never sought to impose his signature on his designs, nor did he achieve ‘star’ status as Clarice Cliff did at Shorters. Unlike Suzy Cooper he eschewed self-promotion and the drive to go it alone. Of course, his greatest support, proxy though it may have been, came from the buying public who purchased large quantities of the wares upon which his designs were featured. This included Queen Mary who, upon viewing his Mattajade range at the British Industries Fair in 1932 purchased a large range of shapes and designs. She expressed a particular liking for his Dragon patterns. So who was Enoch Boulton the man? Snippets of conversations with his widow, correspondence from fellow Director Reginald Fielding to Freda Boulton on the occasion of his death, word of mouth reports from now fading or deceased Fielding’s staff and anecdotes shared by prominent Crown Devon collectors help draw to some extent a sketch of his personality. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Known affectionately as “Ernie”, he was said to be a gentle and unassuming man, but was clearly not a pushover. Modesty did not in any way inhibit the expression of his talent and he was a ‘name’ in the industry when Abraham Fielding decided to lure him away from Wilshaw and Robinson in 1929. He was an exceptionally congenial personality who had a flair for networking, forming fast friendships with Reginald Fielding, Ned Taylor, George Barker, Fred Turner and many other industry figures in the Potteries. In the various reports about him, based on Fieldings staff lower down the chain, it is clear that he was widely liked and respected and thus, a portrait of a moderately reserved though agreeable character emerges, a man whom exuded some of the stronger and more attractive Victorian sensitivities and principles. Boulton was a working class child destined to better himself. From the humble beginnings of an apprentice, he demonstrated abilities very early in his career that were superior to that of a worker on the factory floor. He was noticed and indeed nurtured at Wilshaw and Robinson, rising to the chief design position at Carlton Ware in less than 14 years. It must be remembered that in early twentieth century Britain, merit did not always guarantee one a rise in station, and for Boulton to be given the opportunities he was given he must have shone well above his peers. He was undoubtedly smart and indeed tough enough to position himself for advancement and ultimately to have plotted a career that took him to the top of the vocational pile. Ambition was clearly part of the Boulton character, accompanied by a quiet confidence in his growing abilities as an artist and designer. He was, according to Freda Boulton, a fine painter and his interest in, and love of, painting remained with him all his life. Boulton’s bolder side was revealed in the risks he took with his designs and the confidence he showed in his ability to win the hearts of the risky higher end of the market with his richly decorated and enamelled lustre and matt wares. Of Boulton’s humour little has been recorded, but when one explores Fieldings’ novelties during his watch as design chief, a mischievous and somewhat earthy humour surfaces. It reaches scatological proportions with the patriotic, but tongue in cheek, call to owners of British bottoms to let loose on a caricature of Adolf Hitler that was featured on the base of one of his musical chamber pots! Boulton reserved the same fate for Mussolini, thus demonstrating his legendary evenness of hand. One can only imagine the jocularity the Hitler potty evoked amongst his football mates and Ned Turner, George Barker and his other Fieldings’ confederates. One’s humour drains, however, when confronted with a British dealer who had a price tag of nine hundred pounds for a mint example of the Hitler musical potty. Next to nothing is known of Boulton’s foibles except that of his shamelessness when it came to recognising and expropriating a good idea. Boulton played his part in the fierce rivalry between Wiltshaw & Robinson and Fieldings, and such was the contest between these two potteries that even experts confuse the wares of one with the other. The sports mad Fieldings approached this contest very much as a team game, and, as a consummate team player, Boulton was not averse to suspect ‘play’ behind the ref’s back. When one researches the roots of many of the Boulton designs in the third decade of the twentieth century, one can’t help but be amazed by the breadth of influences he brought to bear on the Devon Pottery’s output. This was a man who loved his work and it is expressed in the volume, diversity and quality of his designs. His understanding of the trends, whims and methods of decorative design and production across Europe, combined with a detailed grasp of his key markets, made him a formidable presence in the highly competitive world of British ceramics. A company’s reputation is always based on it best wares. Enoch Boulton, more than any other individual in the design history of Crown Devon, can be seen as a key figure on whose shoulders the reputation of the Devon Pottery rests today. Much of Enoch Boulton’s story is yet untold, and time is fast running out if we are to avoid the inevitable mythmaking that ensues when facts dry up or die with those who hold them. I would be eternally grateful for any information or ideas on the character, career and design output of Enoch Boulton. Together we might just be able to place enough pieces of the Boulton jigsaw together to ensure he gains his rightful place in the design history of populist British Art Deco. |

||

![]()

![]()

Questions, comments, contributions? email: Steve Birks