|

Three stages of life

It was somewhat unique for a boy of ten to be started on three stages of life before he touched his eleventh year. I had begun as old Betty's scholar at about three.

I had then begun to work at seven, and after working a little short of three years my career was suddenly arrested. I had tried in my poor way to earn my living, though such a young sojourner in the world, but having failed to do this my country came to my rescue to save me from starvation. Suddenly I might have become a gentleman's son, with no need for work, and "only to go to school."

So I went to school instead of to my work as a handle-maker, and to a workhouse where I had no work to do. If I had been a philosopher at that time, I might have been puzzled at these contradictions and caprices, but I was only a boy and took what came before me as a horse takes a road, not asking why it is paved or unpaved, muddy and soft, or clean and hard.

"As I came down the hill

... to Tunstall Church, everything seemed to welcome me"

Leaving Chell Workhouse

But now the one dominant feeling I had was one of exultant joy. All the world was changed that day when I left Chell Workhouse. It was a grey day when I went there, with a chilling air. It was now four or five weeks nearer mid-winter, yet I have no remembrance of greyness or chilliness. All seemed sunshine and gladness. As I came down the hill from Chell to Pittshill, and then on to Tunstall Church, everything seemed to welcome me. We had stealthily gone to Chell by field-paths as far as possible, but we came back by the high road. Everybody seemed to smile upon us and say they were glad to see us.

Tunstall itself, my native town, seemed to put its arms round me as a mother who had lost her child for a time and had recovered him. Of course, all this was illusion on my part, but illusions are sweet when they are born of a real experience. If the people I met and the places I passed were not glad to see me, as I supposed, I was glad to see them, and that was joy enough for me sixty years ago.

Few realities I have met with since have given me as much joy as those illusions did. The world was now to me a great, glad place, full of freedom and hope, and yet if the experience of the next ten years could have been foreseen it would have been found what bitter mockeries my hopes were. But I was free now. I had escaped the loathsome terror of the workhouse, where my whole career might have been poisoned at its source.

Father's previous employer

My father had had a situation offered him as a painter and gilder by a toy manufacturer, a friend of his. His late employer's vengeance had been gratified and his prophecy fulfilled.

The year that man drove my father to the workhouse, I have since learned, he bought an estate for about

£200,000. Yet trade was so bad he had to reduce the wages of his painters and gilders.

I will not say how Nemesis has worked since, but that estate belongs to no descendant of his to-day.

Fortunately for me and others, his influence did not rule at the toy manufactory, or we might have been forced to longer residence in the Bastile, with what issues God only knows. That employer has been dead for many years, and the grand mansion he then resided in has been pulled down, but the issues and memories of his vindictiveness cannot be so easily removed. I have long since forgiven him and pitied him as the creature of his time. The times then were hard and cruel for the poor. The rich were hampered with the notion they must not be resisted, and so even justice, in resistance to the rich, was counted as insolence in the poor. In such a time a man might make a mistake, even tragic in its consequences. That man made a mistake, and one which, could he have foreseen the cruel wrongs and memories it gave birth to, in his life and after his death, I am sure he would have shrunk from.

Work as a toy maker

When I left the workhouse I became a toy-maker, just as my father had become a toy-painter and gilder. My new work introduced me to a few curious circumstances. My new employer was a man who had been seriously reduced only a few years before he took this toy factory. I remembered seeing him, before his trouble came, on his white horse. He was considered a good horseman, and was to be seen daily about the town. He had then an earthenware manufactory, and was, in what was then considered, a large way of business. George H. was a man everyone liked, gentle and simple. He had a breezy heartiness, and a "hail-fellow-well-met" air always about him. He was a conspicuous figure among "the gentlemen" who used to attend the bowling green of "the High-gate Inn." That green was sacredly reserved for "the gentry."

George H. was an old friend of my grandfather's, and so befriended his son in his need. He was now outside the circle of boycotting manufacturers. He was a short, stout man, with a notable head and face. His head and face had a sort of rude majesty about them. They compelled attention, and they had that cheery, hearty something of which John Bull is always typical.

Poor fellow, as I saw him afterwards, in a little, stuffy room, moulding little toper publicans and other figures, and thought of his carollings on his white horse, I could not but pity him. He was like a great lion in a small cage, but without the rage. He was silently enduring. He had no sour memories, and no bitter words do

I remember ever falling from his lips, though I worked near him day by day. He was like a man who, in a way, glorifies misfortune by a quiet magnanimity.

He was said to have been deeply wronged by a principal servant, yet I heard no word fall from his lips about this man. One day, however, he gave me a fearful shock which I shall never forget. He and I worked back to back at benches on each side of a small room. One day I turned round and saw him lifting the top of his head off. I was thrilled with horror and unable to move. I had never seen a wig, nor heard of such a thing; and even when I saw him drop his wig on his head again I hardly knew whether to regard him as a man or a demon. He never saw or knew of my horror, and it was only when I told the incident that night at home that my mind was set at rest. This reference to "home" reminds me that I have forgotten to mention our recovered home on the night of the day we returned from the workhouse.

It would be difficult to describe the place provided for us on our return, yet Patti can never give to the words, "Home, sweet home," the thrill of emotion I felt that night. Its furniture was so scant I cannot describe it. For one thing, even in a wild dream, I could not have fallen out of bed.

Our first meal there was a supper, poor enough, but no harsh bell rang us to it, and no schoolmaster's grace fell upon it to poison it, or make it almost repulsive. In fact, I have no recollection of any grace being said, nor was there any need. It shone on our faces and moved in our hearts. We were free in our own home. To see one's father and mother too at the same table, after an absence which, by its poignancy, seemed very long. Every element in that new life was a joy because it brought back the life of which we had been so suddenly and cruelly robbed.

I went to bed in a bare room, but it was not haunted. I heard no young voices pouring out hoary blasphemies against the schoolmaster and governor. I heard no stifled sobs of timid children, who were appalled by what they heard and the fear of all that was about them. Guardian angels might now have been in that room, shedding upon me the healing of their wings. Between me and the highest heaven there was " peace, perfect peace," and so I rested for the first time for weeks without a wakeful fear keeping my eyes open.

Holecroft - "Th' Hell Hole"

"TH' HELL HOLE"

The neighbourhood in which this toy manufactory stood was then called "Th' Hell Hole" in the town of Burslem. This lurid designation was one of those popular descriptions which often amaze us by their truthfulness and their vivid perception. This description in its directness and grimness could not have been truer though given by a Shakespearian pen. In squalor, in wretchedness, in dilapidation of cottages, in half-starved and half-dressed women and children, in the number of idle and drunken men, it was as terribly dismal as its name would suggest.

Drunkenness and semi-starvation, broken pavements, open drains, and loud-mouthed cursing and obscenity seemed its normal conditions. As the window of the room in which I worked overlooked the main thoroughfare, I was a forced daily observer of all this vile presentment. I don't know what form of Local Government prevailed in the town. I know there was no Local Board and no Corporation. There was a chief bailiff, but what he was chief of Heaven knows.

There were gentlemen manufacturers going about daily in swallow-tailed coats and tall silk hats. There were doctors, and clergymen, and ministers, and yet I never heard a complaint about the doings and conditions of this "Hell Hole." Bullies and their victims lived there, and for unsanitariness and immorality I should think it could not have been surpassed in all England. Sixty years ago this was a slum in the town carrying the proud name of "the Mother of the Potteries."

Wedgwood and Etruria

Josiah Wedgwood, its great son, had left his native town many years before to prosecute his brilliant work in Etruria, a village a few miles away. Etruria, by its very name, would seem to indicate a place of classic beauty. I am afraid, from my remembrance of it in those early days, its architectural achievements and sanitary conditions were not quite a world removed from those of Burslem.

Josiah Wedgwood found the trade of Burslem rude and crude, but started it on a noble career, yet the town of his birth he left very much as he found it. I am not saying this to his dispraise. He wrought marvels in the art of potting, but the time of social marvels was not yet. Within a mile east or west of this "Hell Hole" there were sweet fields and country lanes. To the north of it, within a quarter of a mile, there was the old windmill on a breezy upland overlooking the very market-place, and to the south of it, at a short distance, was Sneyd Green, then a pretty, old-fashioned village as yet undisturbed by the coal industry, which, since then, in its outward aspects, has blighted and scarred it. This "Hell Hole " was only a stupid creation of ignorance, folly and greed which crowded a

narrow area with cheap houses, irrespective of the health, life or character of its denizens. It was a grim monument of what even some good and excellent people can do when their greed counsels their power and opportunity. It was a ghastly proof of the need of such work as that introduced by Edwin Chadwick, and which has now gained beneficent and magnificent incarnation in all the works of municipal government.

In the early days of " Th' Hell Hole," Burslem would be leavened largely by good Churchmen and Methodists. The latter were a large and powerful section of the community, yet, while often singing about the beauties and delights of the " New Jerusalem," they could allow a part of the town to be made a " devil's ground " for the ruin of bodies and souls. It would not do to allow even saints to build a city on green fields without restraints, if they owned them. Force may be no remedy for some things, but it has the action of grace in some departments of our human life. In sanitary affairs, at anyrate, it has made " the habitation of dragons" a way for the

redeemed to walk there with joy and gladness.

'rusty and grim'

A TOY MANUFACTORY

The toy manufactory itself was a curiosity in structure and management. It was rusty and grim. As to form, it might have been brought in

cartloads from the broken-down cottages on the opposite side of the street. The workshops were neither square, nor round, nor oblong. They were a jumble of the oddest imaginable kind, and if there had been the ordinary number of workshops on an average-sized pot-works, placed as these were placed, it would have been impossible to have found the way in and the way out. As it was, though so small, it was rather difficult. The one cart-road went round a hovel nearly, and then dived under a twisted archway. Only about a dozen people were employed on this "bank," and if we all turned out together we were thronged in the narrow spaces outside the shops.

To be "master" of such a place as this poor G. H. had had to come down from his white horse and from his much larger works at Tunstall. So the world has been jogging and jolting for

centuries, jolting some upwards and jogging some downwards.

'the leading article of our industry at this toy

factory'

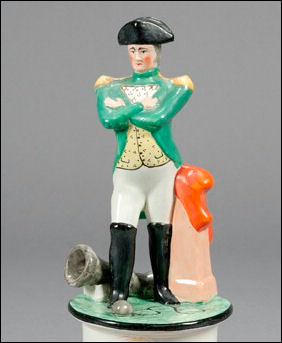

I remember the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte was the leading article of our industry at this toy factory. When Napoleon was finished he stood up with arms folded across his breast, his right leg a little forward, looking defiance at his own English makers. He had a dark blue coat on, tightly buttoned, a buff waistcoat and white breeches. There were touches of gold on his coat and on his large black hat, with flat sides and point, with a high peak. These Napoleons must have been in large demand somewhere, for shoals of them were made at that time.

It is curious how a man who thirty years before had been a veritable ogre and demon to the Eng¬lish people should now have become so popular. If all the Napoleons made at this toy manufactory could have had life given them, then England, if not invaded, would have been crowded by military Frenchmen, and of the dreaded Napoleonic type.

I remember looking pensively at the figure many times, and wondering about all he had been a generation before, and of which I had heard so much.

It is difficult in these days to realise how the terror of Napoleon had saturated the minds of the lower classes in England. Yet, as I looked at the figure, it only then represented a name.

At this toy manufactory we did not make many figures so tragic and terrible in suggestion as Napoleon. George H. had designed a little toper publican with his left hand in his breeches pocket, and in his right hand a jug full of foaming beer. The face wore a flabby smile, which carried welcome to all.

We made cats, too, on box lids, representing cushions. We made dogs of all sizes, from "

Dignity " to "Impudence." We made the gentlest of swains and the sweetest of maids, nearly always standing under the shade of a tree, whose foliage must have been blighted some spring day by an east wind, as it was so sparse in what seemed to be midsummer time.

It is astonishing what amiable squinting those swains and maids did in pretending not to look at each other. I have never seen squinting so

amiable looking in real life. But that was where the art came in. The course of life in this little toy-works was always pleasant. There was nothing strenuous or harsh. "The master" was the

president of a small republic of workers. All were equal in a sort of regulated inequality. We did different work, of different grades of importance and value, and yet no one seemed to think himself better than anyone else.

We had no drunkenness and immorality such as I had seen elsewhere in the same town at a "bank," which would, if it could, have looked down on our "toy" place as the Pharisee looked on the publican. There have been worse employers than George H., even in his adversity, and his little place of business was a quiet refuge for a few toilers, and one free from the demoralising influences prevailing in much larger concerns.

I felt a distinct access of better influences while I worked for George H., and though he never spoke of religion, while placing no obstacle in the way of its pursuit, it was easier to follow it there than at some works whose "masters" wore broad phylacteries on Sundays.

THE EXTREME OF POVERTY

Right opposite the shop I worked in was a house more tumble-down, if possible, than any of the rest. It was approached from the street by a shelving clay bank about two yards above the level of the street. This ascent was unpaved, and was roughly stepped by treading on the clay bank. In this squalid-looking house lived a squalid-looking man, with a squalid-looking wife and with several squalid-looking children. The man was called "Owd Rafe " (Ralph).

He was an "odd man " on a pot bank, who did all sorts of rough, irregular work. He was considered half daft. This arose, however, more from an impediment in his speech rather than from any special mental weakness. This made the poor wretch's life all the more miserable because he knew he was not what he was taken to be. He was miserable enough, for what he earned only kept himself and his family from starvation.

His difficulty in speaking was both painful and ludicrous. It was said that one morning he went home to his

breakfast and asked his wife what there was for breakfast, and she answered, "Roasted potatoes." He went to his dinner, and in reply to his inquiry got the same answer. He went home at night, and asked what there was for his supper, and he got the same reply. The poor wretch, moved by a useless indignation, called out in a fit of dreadful stammering, "Roky taker (roasted potatoes) brekka (breakfast), roky taker dinner, roky taker sukka (supper), dam, bass, roky taker."

This was one of the cries - pathetic, comic and tragic in its way

- among thousands which arose in that day as the result of the starvation and rent-producing policy of Protection. Poor Ralph never lived to see the times of a wiser policy. He died and was put in a workhouse coffin, and on the day of his funeral, as the bearers were bringing the bier and coffin down the clay bank in front of his house, they either slipped through the wretched condition of the bank or through semi-drunkenness, with the result that poor Ralph's body came out of the miserable shell the workhouse had supplied. His poor "remains" had to be re-coffined, so that before his body got to the grave it had been

committed "earth to earth" without the Church's ceremony.

Let us hope that the angels which took Lazarus to Abraham's bosom took better care of Ralph's soul than the bearers of the parish coffin did of his body. These were grim days, but equally grim was the unconcern of the people themselves and "their betters." The former, perhaps, were so degraded or hardened, or

maddened, as to look at these things with stolid defiance or indifference. But for "their betters," their callousness is unexplainable to me even yet. When 1 remember the men who stood at the head of affairs in the town at the time, I am amazed that such a house as Poor Ralph's should have been allowed to stand in such a place. But "Th' Hell Hole" itself might have been as far away as hell for any love or care I ever saw bestowed upon its dwellers while I worked there.

the poverty of the

people... which both Church and State.. upheld

With what reverberations Carlyle's words, "mostly fools," come rolling through my memory as I think of many things which existed among the poor sixty years ago. We might be sixty centuries away from those times, and yet though no millennium is at hand, there is an immense change for the better in many ways and in many conditions. Adverse conditions now are largely self-imposed. In the times of which I write, they were imposed by reckless power, by heedless tyranny, and by fathomless fatuousness which was called statesmanship.

The ignorance of the people, the poverty of the people, and their helplessness, were the

deliberate and direct issues of a certain policy which both Church and State sanctioned and upheld.

Of course, the people, as effective factors in these two institutions, were nowhere, legislators and bishops, the guardians of all privileges, thought the people should be kept in humble ignorance and humble poverty. Humbleness was so highly praised in the Scriptures, and also in some churches. If the poor stood and reverently watched the rich going to church on Sunday morning, that was as it should be.

A few of them, of course, were encouraged to go into the churches, to make up the proper contrast between the rich and the poor, so that whatever grace there was in their "meeting together" might fall upon those who so condescended to meet.

drink more beer

While ignorance and poverty so abounded, the aforesaid legislators thought it well to comfort the poor by inducing them to drink more beer.

So beer-houses were multiplied. I remember how "tuppenny a'-penny" beer-houses sprang up all round my own home.

If a man could get a barrel of beer into his little coal cellar, he became a beer-seller. I didn't know what it meant at the time, but I frequently saw and heard the contrivances and purposes of certain men discussed, by which they might

become beer-sellers. They wanted to eke out a living for themselves, but I am certain, in some cases, the poor fools never thought they were going to do this by lessening the living of their poor neighbours. But such was the transcendent and beneficent wisdom of our legislators

- representatives, and lords spiritual and temporal - exhibited in a time of extreme ignorance and poverty within the last seventy years.

This was not the work of a degraded democracy, thinking only of its own lusts and passions.

It was done by the culture, the privilege, and the power of those who ought to have known better. Those beer-houses have spread disastrous issues through all these years, and it has required the full activity of all the better influences of later legislation, in education and progress, to resist the baneful legacy of the wisdom of the wise.

Mr Gladstone has said "the business of the last half century has been in the main a process of setting free the individual man, that he may work out his vocation without wanton hindrance, as his Maker will have him do."

This statement carries the fact that the

individual man in the first half of the century was bound down by a "wanton hindrance," against the purpose of the great Maker of men. This wanton hindrance was seen in keeping the people ignorant, in keeping them poor, in maintaining harsh laws against all self-help, as in the

conditions and price of their labour, and as in making their food dear when their labour was kept at the lowest value.

Yet, in spite of this disastrous and degrading achievement of aristocracy in the latter part of the eighteenth and the early part of the nineteenth century, I have seen the question

recently asked, "Why are we disappointed with democracy?"

Following this question was the statement that "we used to believe that, when once the great mass of our fellow citizens had obtained control over the machine of State, they would use it energetically and persistently in the creation of better moral and material surroundings for those who cannot help themselves." Then we are told that this among other great

expectations " has been ludicrously falsified."

a land of contrasted

illusions

When I read these words, I wondered whether I had lived for nearly seventy years in a land of contrasted illusions.

I asked myself whether it was true that I was allowed to be worked for fourteen hours a day when a little over seven years of age?

Whether it was true that I had no education beyond what I received in old Betty Wedgwood's cottage along with George Smith of Coalville and others?

Whether it is true that I now see Board schools almost equalling the colleges of some of the older universities?

Whether it is true that even poor children now receive a better education than what I heard "Tom Hughes" once say he received when a boy at a much greater cost?

I wonder whether it is true that children are not permitted now to begin to work until thirteen years of age, quite double the age of thousands of children when I was a child?

I wonder if it is true that I ate the sparse and miserably adulterated bread of the Corn Law times;

if the rags, and squalor, and severe labour and long hours of those days, as contrasted with the leisure, and plenty, and

recreation of these days are all illusions?

I wonder if these are real people in their thronging

thousands, on holiday, that I see, who have shares in "stores," who have deposits in the savings banks, who have portmanteaus, boxes of all sizes and kinds, making up tons of luggage in connection with a trip, surpassing that of "their betters" seventy years ago?

I

wonder if the holidayless England I knew in my youth, when the bulk of the people in the Midlands had never seen the sea, and the holidays of to-day, with their flowing wealth and freedom and joy, are grotesque,

because contradictory, illusions, having no "local habitation " but in my disordered brain?

I know democracy has been disappointing in many great moral and intellectual issues, but to say that it has "ludicrously failed" to create "better moral and material surroundings" is to contradict history, and more, the living, burning and agonising experience of those who lived sixty to seventy years ago.

I hope democracy will not always be " indifferent to the cry of human suffering," "disregard justice when separated from self-interest," or "always delight in war."

But however it has failed, it is not likely to take England back to the conditions of life prevailing in the first sixty years of the new industry.

That new industry came like an ogre,

devouring the domesticity and the child-life of England, and to its everlasting disgrace the aristocratic statesmanship of England lent itself to the dread carnival of greed and cruelty. Democracy will never match issues like these, or if it does, then it will be quite time for some " friendly comet " to come and surround us with its destructive embrace.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()