|![]() Index

of all Stoke-on-Trent Mines |

Index

of all Stoke-on-Trent Mines |

Sneyd Colliery, Burslem

Sneyd colliery was located between Burslem and Smallthorne, and not at Sneyd Green which was some one and a half miles away.

Sneyd Colliery in 1925

| The coal wagons on the

right would be filled and taken down to Burslem to join the loop line. Sneyd was modernised extensively and between 1957 and 1964 was linked underground to Hanley Deep and Wolstanton. The mine closed in the 1970ís. |

photo: © The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery

Staffordshire Past Track

Colliery wagons at the coking plant at the Shelton Iron & Steel Works

two sets of winding gear can be seen as well as Sneyd Colliery wagons

in the background is the spoil tip

Sneyd Colliery in 1896...

Situation: Burslem Owner:

Sneyd Colliery and Brickworks Co. Ltd.Address: Burslem, Staffs.

Name of mine: Sneyd No 2

| Manager: | John Heath | ||

| Under Manager: | Wm. Frost | ||

| Workers: |

|

||

| Minerals worked: | Household Coal; Manufacturing Coal; Steam Coal | ||

| Seams worked: | Yard, Ten Feet, Bowling Alley, Holly Lane, Hard Mine | ||

| Remarks: |

Name of mine: Sneyd No 3

| Manager: | John Heath | ||

| Under Manager: | Wm. Frost | ||

| Workers: |

|

||

| Minerals worked: | Household Coal; Manufacturing Coal; Steam Coal; Ironstone | ||

| Seams worked: | Burnwood, Mossfield, Seven Feet, Two Feet | ||

| Remarks: |

From: report by W. N. Atkinson, H.M.

Inspector for North Staffordshire - 1896.

List of Mines worked under the Coal Mines Regulation

Act,

in North Staffordshire, during the Year 1896

Explosion at Sneyd Colliery on New Year's Day 1942

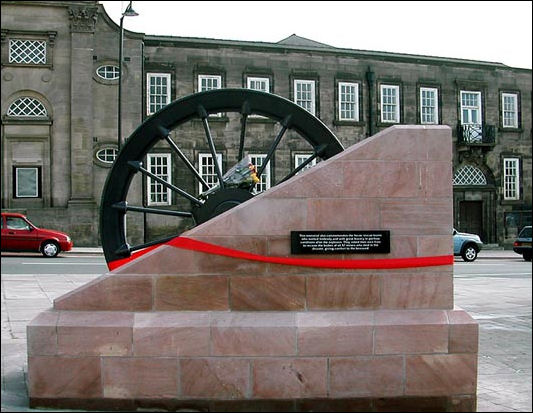

Memorial to those who died at Sneyd Colliery on New

Year's Day 1942

photos: John Lumsdon - 24 Aug 2007

Fred Hughes looks back on the Sneyd Colliery disaster of 1942 and meets a man with a first-hand account of the New Year's Day tragedy.....

January 1 marks the .... anniversary of one of Stoke-on-Trent's darkest days. The nation was into the third year of war and hardship and danger was felt in North Staffordshire as much as it was on the fighting fronts."It wasn't so much a matter of bombing the coalfields," explains former miner and mining historian John Lumsdon, "It was about location. Even with the observance of secrecy and camouflage, which allowed many collieries to escape direct hits, some coalfields sustained aerial attacks. But aside from the war, underground fatalities were just as frequent as they ever were."

The disaster that caused the biggest impact occurred at Sneyd Colliery on New Year's Day 1942.

Because of wartime censorship, it was only later that many of the personal stories emerged.

It is extremely important that those memories are preserved. John Lumsdon puts it into perspective:

"Coal mining is the traditional dangerous job. It was only after nationalisation in 1947 that the industry's safety standards were properly regulated. Before this, each pit was as safe as the individual owners cared to make it. Even at Sneyd, 15 years after nationalisation, 14 men lost their lives in separate accidents, and hundreds more were laid off through injury. Coal mining was a hazardous job and fatalities were a fundamental part of the risks."

That first day in January 1942, the Evening Sentinel's early edition reported that an explosion had occurred at Sneyd at around 7.30am and that three men had been killed and 48 were still trapped.

"I went up to Sneyd that morning to see if I was wanted for the late shift," recalls 93-year-old William Holdcroft. "There was summat up, you could tell, but nobody was saying anything. Somebody announced that the Germans had invaded Britain.

"It was a daft rumour thought up to explain what was going on. Nobody told us the real reason at first. But the bad news came through anyway. Next day, Friday, I was asked to go underground as the bodies were being taken out. I hadn't been at Sneyd long but I'd struck up a friendship with a chap name Len Bromley. A couple Of days before the explosion he'd had a row with an overman. So when I didn't see him on the Friday I thought he'd either walked out or had stayed at home. It didn't occur to me that he'd turned in on New Year's Day and had been killed." William and his young wife Hilda had been living in Sandbach Road, Burslem, at the time.

"Like most mining families, all the men in my family worked in pits," William says. "I was born in Ball Green so my father and brothers were all at Whitfield together. I'd seen men killed underground before but nothing could prepare me for what happened at Sneyd."

As Thursday moved into Friday, the full horror of the explosion became apparent across the region.

"It made me bad to see so many bodies being brought out," says William. "I was so ill that I couldn't go in on Saturday. It finished me." Even as the tragedy descended upon Burslem, normal life was far from safe. "In that same week a bomb was dropped near where we lived in Sandbach Road," recalls William. "It was as though the Germans were aiming for Sneyd even after all those men had died there."

The Sneyd explosion claimed 57 lives. The traditional day off for New Year had been put aside because of the war effort and 295 men were working in No 4 Pit at the time. By late Friday, the Evening Sentinel gave the names of the miners who had been killed. "You put bad things out of your mind," murmurs William.

"After the war I never gave a thought to Len Bromley until they put the memorial up in Burslem. I asked my son to take me down and I saw his name carved in the plaque." A fitting memorial was erected in Burslem town centre in 2007.

Fred Hughes, The Sentinel newspaper Dec 29 2007

| On January 1st. 1942,

fifty-seven men and boys lay down their lives for King and Country just as

if they had been fighting with the armed forces. Their deaths were not

caused by enemy action but by a horrific underground explosion at Sneyd

Colliery on the outskirts of Burslem and Smallthorne, bringing great

sorrow and grief to the community.

It's sad to think that in normal times the pit would not have been worked on New Year's Day, but due to the urgent demand for coal, to make the instruments of war, the manager appealed to the men to work, and they whole-heartedly responded. The tragic explosion occurred at 7.50 am. on January 1st. 1942, 800 yards below ground. The first report was that seven men were dead and fifty-one were missing.

Rescue work began immediately, and four of the victims, two of whom died in hospital later, were found close to the pit bottom. The other three bodies were recovered as rescue workers forced their way through the debris. The trapped men were working in the Seven Feet Banbury Seam of No. 4 pit. There were two faces in the district concerned, 21s and 22s, one being 1,000 yards from the pit bottom and the other 600 yards. One road was clear and an investigation being made along it, but the other road was blocked by falls of roof. There had simply been an explosion but there was no exact idea as to where it had occurred. The explosion had not affected any other part of the pit, so immediately after the occurrence all workers were withdrawn from No. 4 and No. 2 pits. Assistance was readily available from other colliery managers in the district and from rescue teams, the cream of the industry, from other pits, Chatterley Whitfield, Black Bull, Hanley Deep and Shelton. Sadly, later on in the day all hope had been abandoned of recovering alive anyone left in the pit. Mr. I. W. Cumberbatch, director and general manager of the Sneyd Collieries, made the following statement at 1 pm. on January 1st:-

Rescue work went ahead unceasing with all possible speed, but by 6 pm. the rescue workers were still 200 yards from the coalface. Another official statement was issued on Friday morning:-

Seventy nine percent of the under-ground workers employed on the day shift reported for duty on Monday when work was resumed at the colliery. High appreciation of the workers' response was expressed by Mr. Cumberbatch, who in a statement said:-

On Tuesday morning, 94% of the day shift workers in No. 4 pit, reported for duty and there was a 100% attendance in respect of No 2 pit. By January 9th, the bodies of every man and boy had been recovered. This represented a marvellous achievement, recognised by anyone having knowledge of the dangerous conditions that prevail following an explosion.

In order to find the cause of the explosion there was a most searching investigation, with the services of experts in mining, electricity, and under-ground ventilation being enlisted from all parts of the country. Evidence showed that at the top of the Banbury Crut Jig (a haulage roadway) the force of the explosion was inbye (towards the coal face) and from the bottom it was out bye (towards the shaft). Having assimilated the evidence given at the inquiry and visiting the site, the Government Inspector issued the result as follows:

The ages of the victims ranged from 16-17 year olds to veteran miners....

A shadow was thrown on many homes in the Potteries.....

information in this account of the disaster was researched by John Lumsdon and supplied by the website - Healey Hero

|

![]() Index

of all Stoke-on-Trent Mines |

Index

of all Stoke-on-Trent Mines |

questions/comments/contributions? email: Steve Birks