|

The

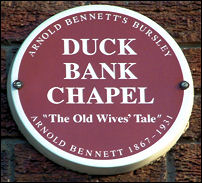

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel and Arnold Bennett

"The Duck

Square region is a little obscure; apparently it is the rather shapeless

little tract between Waterloo Road proper and the market-place, with a

chapel, a school, and a playground on the eastern side. At its south end

(on the south side of Wedgwood Street, that is) stood the Steam

Printing Works of Darius Clayhanger ; Mr Duncalf's office, first scene of

the Card's activities, was also in the Square.

Here again

is a ganglion of roads, the chief of them Waterloo (" Trafalgar ") Road,

the main trunk line between Hanbridge and Bursley. Where Trafalgar Road

joined it Aboukir Road" or " Warm Lane" (Nile

Street) stood the " Dragon," while exactly parallel to Trafalgar Road, for

some distance, ran "Woodisun Bank."

The two

Methodist chapels Primitive and Wesleyan are said to have been in King

Street and Duck Bank respectively; but certain details here are

incongruous with to-day's topography. The other Anglican Church, St Paul's

(" St Peter's"), is a little distance due north-east of the

market-place..."

from..

"Writers of the Day" - general editor: Bertram Christian

The Methodist - the ideal workman

"If potting was the industry of the district,

Methodism was its religion, and the two together formed the Bennett

inheritance. By the time Bennett was born, religion was a more potent

force than potting in the family. The first member of the Bennett family

to take the significant step of becoming a Wesleyan Methodist was Sampson,

son of John the potter; he joined the Methodist faith round about the year

1816, by which time Methodism was flourishing all over the Potteries. It

was a religion ideally suited to the district, as Wesley found when he

visited Burslem: his first visit, in 1760, was rather a wash-out because,

as he crossly remarked in his Journal, 'the cold considerably

lessened the congregation. Such is human wisdom! So small are the things

which divert mankind from what might be the means of their eternal

salvation!'

But the word did not fall on deaf ears, for he

made converts; when he went back three years later he found 'a large

congregation at Burslem; these poor potters four years ago were as wild

and ignorant as any of the colliers in Kingswood. Lord' [he says,

enigmatically, possibly intending a pun?],

'thou hast power over thine own

clay!' (a)

After this, Methodism spread rapidly, and chapels

sprang up all over the Five Towns: the first was built in 1766, and

chapel-building went on right through the decline of the congregations at

the end of the nineteenth century, for, as Bennett cynically observes in

These Twain, the response of the Wesleyan community to a falling

attendance and shortage of ministers was to 'prove that Wesleyanism was

spiritually vigorous by the odd method of building more chapels'. (b)

At the beginning, however, Wesleyanism was truly a religion of the

people and for the people. It was a genuine working-class movement,

which offered spiritual hope and material improvement to its followers.

It offered education, betterment, a brighter future in material terms,

and an emotional release from the grim realities of the present. It

preached thrift, discipline and frugality. Unfortunately these very

virtues were to become weapons in the hands of the employers, and

created the ambiguous attitudes to wealth and self-help and industry

that were almost to ruin the religion's spiritual power.

The Methodist was the ideal workman, as the

employers were quick to realize: Robert Peel, writing in 1787, says: 'I

have left most of my works in Lancashire in the management of Methodists,

and they have served me excellently well.' (c)

The improved Methodist, with honestly saved money

in his pocket, became just as repressive and worldly as the churchmen he

had despised. Wesley himself foresaw this dilemma, when he wrote:

'. .. religion must necessarily produce both

industry and frugality, and these cannot but produce riches. But as

riches increase, so will anger and pride and love of the world. . . .

How then is it possible that Methodism, that is, a religion of the

heart, though it now flourishes as a green bay tree, should continue in

this state? For the Methodists in every place grow diligent and frugal;

consequently they increase in goods. Hence they disproportionately

increase in pride, in anger, in the desire of the flesh, the desire of

the eyes, and the pride of life.' (d)

from..

"Arnold Bennett a biography pp 8,9" - Margaret Drabble

(a) John Wesley, Journal (London 1827), entries for 19 March

1760 and 20 June 1763-

(b) These Twain, Book i, ch. 3, 'Attack and Repulse'.

(c) Robert Peel, quoted by L.Tyerman in John Wesley (London 1870),

vol. 3, p. 499.

(d) Wesley, op. cit.

From Wesleyan Methodist Chapel to Paris Brothel

"The Old Wives' Tale

celebrates the romance of even the most ordinary lives in the course of

tracing the passage of time over three generations. It tells the story

of the two Baines sisters, placid stay-at-home Constance and rebellious

Sophia, from their girlhood to their last days. They move from the

family drapery shop in provincial Bursley during the repressive

mid-Victorian period to old age in the modern era of mass marketing and

the internal combustion engine. The setting ranges from the Wesleyan

Methodist Chapel in Bursley to a Paris brothel, the action from the

controlled domestic routine of the Baines household to wife murder and

the Siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1."

"In the

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on Duck Bank there was a full and

influential congregation. For in those days influential people were

not merely content to live in the town where their fathers had lived,

without dreaming of country residences and smokeless air--they were

content also to believe what their fathers had

believed about the beginning and the end of all. There was no such

thing as the unknowable in those days. The eternal mysteries were as

simple as an addition sum; a child could tell you with absolute

certainty where you would be and what you would be doing a million

years hence, and exactly what God thought of you. Accordingly, every

one being of the same mind, every one met on certain occasions in

certain places in order to express the universal mind. And in the

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, for example, instead of a sparse handful of

persons disturbingly conscious of being in a minority, as now, a

magnificent and proud majority had collected, deeply aware of its

rightness and its correctness."

"Strange that immortal souls should

be found with the temerity to reflect upon mundane affairs in that

hour! Yet there were undoubtedly such in the congregation; there

were perhaps many to

whom the vision, if clear, was spasmodic and fleeting. And among

them the inhabitants of the Baines family pew! Who would have

supposed that Mr. Povey, a recent convert from Primitive Methodism

in King Street to Wesleyan Methodism on Duck Bank, was dwelling upon

window-tickets and the injustice of women, instead of upon his

relations with Jehovah and the tailed one? Who would have supposed

that the gentle-eyed Constance, pattern of daughters, was risking

her eternal welfare by smiling at the tailed one, who, concealing

his tail, had assumed the image of Mr. Povey? Who would have

supposed that Mrs. Baines, instead of resolving that Jehovah and not

the tailed one should have ultimate rule over her, was resolving

that she and not Mr. Povey should have ultimate rule over her house

and shop? It was a pew-ful that belied its highly satisfactory

appearance. (And possibly there were other pew-fuls equally

deceptive.)"

"The Old Wives'

Tale" Arnold Bennett |

Bible Class on

Saturdays!

"Six months previously a young minister of the Wesleyan Circuit, to

whom Heaven had denied both a sense of humour and a sense of honour,

had committed the infamy of starting a Bible class for big boys on

Saturday afternoons. This outrage had appalled and disgusted the

boyhood of Wesleyanism in Bursley. Their afternoon for games, their

only fair afternoon in the desert of the week, to be filched from them

and used against them for such an odious purpose as a Bible class! Not

only Sunday school on Sunday afternoon, but a Bible class on Saturday

afternoon! It was incredible. It was unbearable. It was gross tyranny,

and nothing else.

Nevertheless the young minister had

his way, by dint of meanly calling upon parents and invoking their

help. The scurvy worm actually got together a class of twelve to

fifteen boys, to the end of securing their eternal welfare. And they

had to attend the class, though they swore they never would, and they

had to sing hymns, and they had to kneel and listen to prayers, and

they had to listen to the most intolerable tedium, and to take notes

of it. All this, while the sun was shining, or the rain was raining,

on fields and streets and open spaces and ponds!"

Edwin Clayhanger

joins the Young Men's Debating Society

"The Young Men's

Debating Society was a newly formed branch of the multifarous activity

of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. It met on Sunday because Sunday was

the only day that would suit everybody; and at six in the morning for

two reasons. The obvious reason was that at any other hour its

meetings would clash either with other activities or with the

solemnity of Sabbath meals. This obvious reason could not have stood

by itself; it was secretly supported by the recondite reason that the

preposterous hour of 6 a.m. appealed powerfully to something youthful,

perverse, silly, fanatical, and fine in the youths. They discovered

the ascetic's joy in robbing themselves of sleep and in catching

chills, and in disturbing households and chapel-keepers. They thought

it was a great thing to be discussing intellectual topics at an hour

when a town that ignorantly scorned intellectuality was snoring in all

its heavy brutishness. And it was a great thing. They considered

themselves the salt of the earth, or of that part of the earth. And I

have an idea that they were.

Edwin had joined this

Society partly because he did not possess the art of refusing, partly

because the notion of it appealed spectacularly to the martyr in him,

and partly because it gave him an excuse for ceasing to attend the

afternoon Sunday school, which he loathed. Without such an excuse he

could never have told his father that he meant to give up Sunday

school. He could never have dared to do so. His father had what Edwin

deemed to be a superstitious and hypocritical regard for the Sunday

school. Darius never went near the Sunday school, and assuredly in

business and in home life he did not practise the precepts inculcated

at the Sunday school, and yet he always spoke of the Sunday school

with what was to Edwin a ridiculous reverence. Another of those

problems in his father's character which Edwin gave up in disgust!"

"Clayhanger"

Arnold Bennett |

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()