| thepotteries.org - Local History Documents (illustrative of Stoke-on-Trent, North Staffordshire, England) |

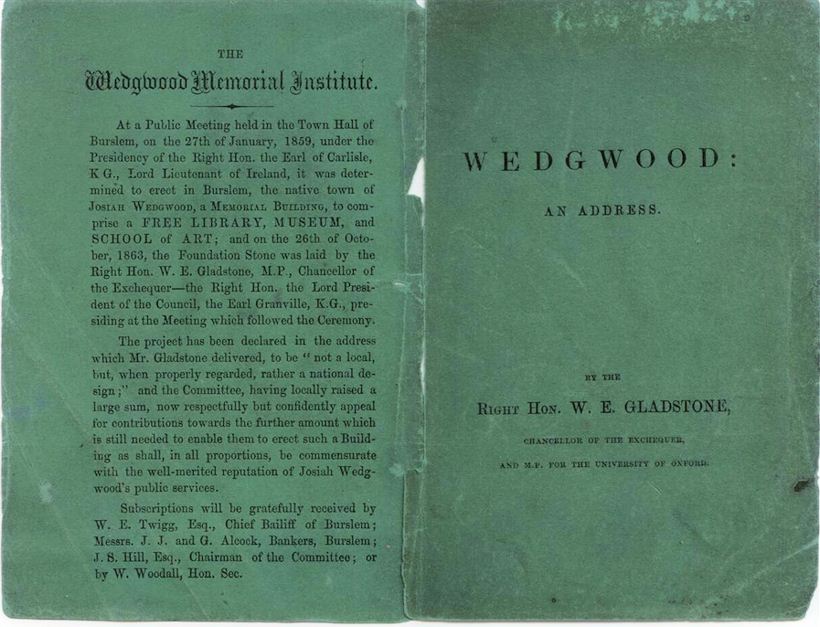

Wedgwood: An Address by the Right Hon W E Gladstone

The copy of the booklet was kindly provided by

Catherine Turnbull (née Gladstone) who is the

Great, Great, Great Niece of Gladstone.

|

The

Wedgwood Institute details of the Wedgwood Institute, built as a library, museum and art school in 1869. |

Wedgwood: An Address by the Right Hon W E Gladstone

Chancellor of the Exchequer

and MP for the University of Oxford

|

The Wedgwood Memorial Institute At a Public Meeting held in the Town Hall of Burslem, on the 27th of January, 1859, under the Presidency of the Right Hon. the Earl of Carlise, KG., Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, it was determined to erect in Burslem, the native town of JOSIAH WEDGWOOD, a MEMORIAL BUILDING, to comprise a FREE LIBRARY, MUSEUM, and SCHOOL of ART; and on the 26th of October, 1863, the Foundation Stone was laid by the Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer - the Right Hon. the Lord President of the Council, the Earl Granville, K.G., presiding at the Meeting which followed the Ceremony. The project has been declared in the address which Mr. Gladstone delivered, to be "not a local, but, when properly regarded, rather a national design;" and the Committee, having locally raised a large sum, now respectfully but confidently appeal for contributions towards the further amount which is still needed to enable them to erect such a Building as shall, in all proportions, be commensurate with the well-merited reputation of Josiah Wedgwood's public services. Subscriptions will be greatfully received by W.E. Twigg, Esq., Chief Baliff of Burslem; Messrs. J.J. and G. Alcock, Bankers, Burslem; J.S. Hill, Esq., Chairman of the Committee; or by W. Woodall, Hon. Sec. |

|

WEDGWOOD ADDRESS, We have now, Ladies and Gentlemen, laid the foundation stone of a building which is destined, as I hope, to do honour, and to produce abundant benefit, to this town and neighbourhood.

p.6 The Institute more than local

The occupations and demands of political life compel many of those who pursue it, and myself among the number, to make a rule of declining all invitations of a local character, except such as lie within their own immediate and personal sphere. But when I received, through one of your respected representatives, an invitation to co-operate with you in the foundation of the Wedgwood Institute, at the place which gave him birth, and on the site of what may, perhaps, be called his earliest factory, I could not hesitate to admit that a design of this kind was, at least in my view, not a local, but, when properly regarded, rather a national design. Partly it may be classed as national, because the manufacture of earthenware, in its varied and innumerable branches, is fast becoming, or has indeed become, one of our great and distinguishing British manufactures.

p.7 Grounds of a personal interest in it

I have engaged, as I am aware, in a somewhat perilous undertaking. For, having come here to speak to you about a man and a business, I am obliged to begin by confessing what, if I did not confess it, you would soon discover for yourselves, namely, that of both of them my knowledge is scanty, theoretic, and remote: while you breathe the air, inherit the traditions, in sorne cases bear the very name of the man; and have a knowledge of the business, founded upon experience and upon interest, in all its turns and stages, and from its outer skin, so to speak, to its innermost core. It is the learner who for the moment stands in the teacher's place, and, instead of listening with submission, seems to aim at speaking with authority. It would be easy to enlarge in this course of remark; but I must stop, or I shall soon demonstrate that I ought not to be here at all. Let me then offer something on the other side.

p.9 Limits of interference with trade

Thirty years ago it would probably have been held by many, and it may still be the thought of some, that the matters, of which I have now to speak, are matters which may well be left to regulate themselves. To vindicate for trade in all its branches the principle and power of self-regulation, has been for nearly a quarter of a century a principal function of the British Parliament. But the very same stage in our political and social existence, which has taught us the true and beneficial application of the laws of political economy, has likewise disclosed to us the just limits of the science, and of the field of its practical application. The very same age, which has seen the State strike off the fetters of industry, has also seen it interpose, with a judicious boldness, for the protection of labour. The same spirit of policy, which has taken from the British producer the enjoyment of a system of virtual bounties, paralyzing to him and most costly to the community at large, has offered, him the aids of knowledge and instruction by whatever means, either of precept or example, public authority could command.

Now, as to their utility and convenience, considered alone, we may leave that to the consumer, who will not buy what does not suit him. As to their cheapness, when once security has been taken that an entire society shall not he forced to pay an artificial price to some of its members for their productions, we may safely commit the question to the action of competition among manufacturers, and of what we term the laws of supply and demand.

This, however, though I may again advert to it, is not for to-day our special subject. We come, then, to the last of the heads which I have named: the association of beauty with utility, each of them taken according to its largest sense, in the business of industrial production. And it is in this department, I conceive, that we are to look for the peculiar pre-eminence, I will not scruple to say the peculiar greatness, of Wedgwood.

p.12 On beauty in industrial products

Now do not let us suppose that, when we speak of this association of beauty with convenience, we speak either of a matter which is light and fanciful, or of one which may, like some of those I have named, be left to take care of itself.

Reject, therefore, the false philosophy of those who will ask what does it matter, provided a thing be useful, whether it be bountiful or not: and say in reply that we will take one lesson from Almighty God, Who in His works hath shown us, and in His Word also has told us, that "He hath made everything." not one thing, or another thing, but everything, " beautiful in His time." Among all the devices of Creation, there is not one more wonderful, whether it be the movement of the heavenly bodies, or the succession of the seasons and the years, or the adaptation of the world and its phenomena to the conditions of human life, or the structure of the eye, or hand, or any other part of the frame of man,— not one of all these is more wonderful, than the profuseness with which the Mighty Maker has been pleased to shed over the works of His hands an endless and boundless beauty.

p.13 Its root in human nature

And to this constitution of things outward, the constitution and mind of man, deranged although they be, still answer from within. Down to the humblest condition of life, down to the lowest and most backward grade of civilization, the nature of man craves, and seems as it were even to cry aloud, for something; some sign or token at the least, of what is beautiful, in some of the many spheres of mind or sense.

It is, in short, difficult for human beings to harden themselves at all points against the impressions and the charm of beauty. Every form of life, that can be called in any sense natural, will admit them. If we look for an exception, we shall perhaps come nearest to finding one in a quarter where it would not at first be expected. I know not whether there is any one among the many species of human aberration, that renders a man so entirely callous, as the lust of gain in its extreme degrees. That passion, where it has full dominion, excludes every other; it shuts out even what might be called redeeming infirmities; it blinds men to the sense of beauty, as much as to the perception of justice and right; cases might even be named of countries, whore greediness for money holds the widest sway, and where unmitigated ugliness is the principal charaeteristic of industrial products.

p.16 Its moral influence in commerce

On the other hand, I do not believe it is extravagant to say, that the pursuit of the element of Beauty, in the business of production, will be found to act with a genial, chastening, and refining influence on the commercial spirit; that, up to a certain point, it is in the nature of a preservative against some of the moral dangers, that beset trading and manufacturing enterprise; and that we are justified in regarding it not merely as an economical benefit; not merely as that which contributes to our works an element of value: not merely as that which supplies a particular faculty of human nature with its proper food; but as a liberalising and civilising power, and an instrument, in its own sphere, of moral and social improvement. Indeed it would be strange, if a deliberate departure from what we see to be the law of Nature in its outward sphere were the road to a close conformity with its innermost and highest laws. But now let us not conceive that, because the love of Beauty finds for itself a place in the general heart of mankind, therefore we need never make it the object of a special attention, or put in action special means to promote and to uphold it. For after all, our attachment to it is a matter of degree, and of degree which experience has shown to be, in different places, and at different times, indefinitely variable. We may not be able to reproduce the age of Pericles, or even that which is known as the Cinque-cento; but yet it depends upon our own choice, whether we shall or shall not have a title to claim kindred, however remotely, with either, aye or with both, of those brilliant periods. What we are bound to, is this: to take care, that everything we produce shall, in its kind and clasa, lie as good as wo can make it When Dr. Johnson, whom I Blip-pose that Staffordshire must ever reckon among her most distinguished ornaments, was asked by Sir. Boswell, how he had attained to his extraordinary excellence iu conversation, ho replied, he had no other rale or system than this: that, whenever he had anything to say, he tried to say it in the best manner he was able. It is this perpetual striving after excellence on the one hand, or the want of such effort on the other, which, more than the original difference of gifts (certain and great as that difference may he), contributes to bring about the differences we observe in the works and characters of men. Now such efforts are more rare, in proportion as the object in view is higher, the reward more distant.

p.18 On aiming at the best

It appears to me that, in the application of Beauty to works of utility, the reward is generally distant. A new element of labour is imported into the process of production; and that element, like others, must be paid for. In the modest publication, which the firm of Wedgwood and Bentley put forth under the name of a Catalogue, but which really contains much sound and useful teaching on the principles of industrial Art, they speak plainly on this subject to the following effect:—

p.19 Special teaching of it why requisite

The beautiful object will be dearer, than one perfectly bare and bald; not because utility is curtailed or compromised for the sake of beauty, but because there may be more manual labour, and there must be more thought, in the original design.—

Therefore the manufacturer, whose daily thought it most and ought to be to cheapen his productions, endeavouring to dispense with all that can be spared, is under much temptation to decline letting Beauty stand as an item in the account of the costs of production. So the pressure of economical laws tells severely upon the finer elements of trade. And yet it may be argued that, in this as in other cases, in the case for example of the durability and solidity of articles, that which appears cheapest at first may not be cheapest in the long run. And this for two reasons. In the first place, because in the long run mankind are willing to pay a price for Beauty. I will seek for a proof of this proposition in an illustrious neighbouring nation. France is the second commercial country of the world; and her command of foreign markets seems clearly referable, in a great degree, to the real elegance of her productions, and to establish in the most intelligible form the principle, that taste has an exchangeable value; that it fetches a price in the markets of the world.

But, furthermore, there seems to be another way, by which the law of nature arrives at its revenge upon the short-sighted lust tor cheapness. We begin, say, by finding Beauty expensive. We accordingly decline to pay a class of artists for producing it. Their employment ceases; and the class itself disappears. Presently we find, by experience, that works reduced to utter baldness do not long satisfy. We have to meet a demand for embellishment of some kind. But we have now starved out the race, who knew the laws and modes of its production. Something, however, must he done. So we substitute strength for flavour, quantity for quality; and we end by producing incongruous excrescences, or even hideous malformations, at a greater cost than would have sufficed for the nourishment among us, without a break, of chaste and virgin Art.

p22 Value of the proposed Institute

Thus, then, the penalty of error may be certain; but it may remain not the less true that the reward of sound judgment and right action, depending as it does not on to-day or to-morrow, but on the far-stretching future, is remote. In the same proportion, it is wise and needful to call in aid all the secondary resources we can command. Among these instruments, and among the best of them, is to be reckoned the foundation of Institutes, such as that which you are now about to establish; for they not only supply the willing with means of instruction, but they bear witness from age to age to the principle on which they are founded; they carry down the tradition of good times through the slumber and the night of bad times, ready to point the path to excellence, when the dawn returns again. I heartily trust the Wedgwood Institute will be one worthy of its founders, and of its object.

p 23 Wedgwood's perception of the true law of industrial art

But now let us draw nearer to the immediate character and office of him, wand fulness with which he perceived the true law of what we term Industrial Art, or in other words, of the application of the higher Art to Industry; the law which teaches us to aim first at giving to every object the greatest possible degree of fitness and convenience for its purpose, and next at making it the vehicle of the highest degree of Beauty which, compatibly with that fitness and convenience, it will bear; which does not, I need hardly say, substitute the secondary for the primary end, but which recognises, as part of the business of production, the study to harmonise the two. To have a strong grasp of this principle, and to work it out to its results in the details of a vast and varied manufacture, is a praise, high enough for any man, at any time, and in any place. But it was higher and more peculiar, as I think, in the case of Wedgwood, than in almost any other case it could be. For that truth of Art, which he saw so clearly, and which lies at the root of excellence, was one, of which England, his country, has not usually had a perception at all corresponding in strength and fulness with her other rare endowments. She has long taken a lead among the nations of Europe for the cheapness of her manufactures: not so for their beauty. And if the day shall ever come, when she shall be as eminent in true taste, as she is now in eeononiy of production, my belief is that that result will probably be due to no other single man in so great a degree as to Wedgwood. This part of the subject, however, deserves a somewhat fuller consideration.

p.25 Three regions of effort

There are three regions given to man for the exercise of his faculties in the production of objects, or the performance of acts, conducive to civilisation, and to the ordinary uses of life. Of these, one is the homely sphere of simple utility. What is done, is done for some purpose of absolute necessity, or of immediate and passing use. What is produced, is produced with an almost exclusive regard to its value in exchange, to the market of the place and day. A dustman, for example, cannot be expected to move with the grace of a fairy ; nor can his cart be constructed on the flowing lines of a Greek chariot of war. Not but that, even in this unpromising domain, Bounty also has her place. But it is limited, and may for the present purpose be left out of view. Then there is, secondly, the lofty sphere of pure thought and its ministering organs, the sphere of Poetry and the highest Arts, Here, again, the place of what we term utility is narrow; and the production of the Beautiful, in one or other of its innumerable forms, is the supreme, if not the only, object. Now, I believe it to be undeniable, that in both of these spheres, widely separated as they are, the faculties of Englishmen, and the distinctions of England, have been of the very first order. In the power of economical production, she is at the head of all the nations of the earth. If in the Fine Arts, in Painting, for example, she must be content with a second place, yet in Poetry, which ranks even higher than Painting,—I hope I am not misled by national feeling when I say it,—she may fairly challenge all the countries of Christendom, and no one of them, but Italy, can as yet enter into serious competition with the land of Shakespeare. But, for one, I should admit that, while thus pre-eminent in the pursuit of pure beauty on the one side, and of unmixed utility on the other, she has been far less fortunate, indeed, for the most part she has been decidedly behindhand, in that intermediate region, where Art is brought into contact with Industry, and where the pair may wed together. This is a region alike vast and diversified. Upwards, it embraces Architecture, an art which, while it affords the noblest scope for grace and grandeur, is also, or rather ought to be, strictly tied down to the purposes of convenience, and has for its chief end to satisfy one of the most imperative and elementary wants of man. Downwards, it extends to a very large proportion of the products of human industry. Some things, indeed, such as scientific instruments for example, are so determined by their purposes to some particular shape, surface, and materials, that even a Wedgwood might find in them little space for the application of his principles. But, while all the objects of trade and manufacture admit of fundamental differences in point of fitness and unfitness, probably the major part of them admit of fundamental differences also in point of Beauty or of Ugliness. Utility ia not to be Sacrificed for Beauty, but they are generally compatible, often positively helpful to each other: and it may lie safely asserted, that the periods, when the study of Beauty has been neglected, have usually been marked not by a more successful pursuit of utility, but by a general decline in the energies of man. In Greece, the fountamhend of all instruction on these matters, the season of her highest historic splendour was also the summer of her classic poetry and art: and in contemplating her architecture, we scarcely know whether most, to admire the acme of Beauty, or the perfect obedience to the laws of mechanical contrivance.

p.29 Our relative inferiority in the middle region

The Arts of Italy were the offspring of her freedom, and with its death they languished and decayed. And let us again advert for a moment to the case of France. In the particular department of industrial art, France, perhaps, of all modern nations, has achieved the greatest distinction : and at the same time there is no country which has displayed, through a long course of ages, a more varied activity, or acquired a greater number of the most conspicuous titles to renown. It would be easy to show that the reputation, which England has long enjoyed with the trading world, has been a reputation for cheap, and not for beautiful, production. In some great branches of manufacture, we were, until lately, dependent upon patterns imported from abroad: in others, our works presented to the eye nothing but a dreary waste of capricious ugliness. Some of us remember with what avidity, thirty or forty years back, the ladies of England, by themselves and by their friends, smuggled, when they had a chance, every article of dress and ornament from France. That practice has now ceased. No doubt the cessation is to bo accounted for by the simple and unquestionable fact that there are no longer any duties to evade: but also the preference itself has in some degree been modified, and that modification is referable to the great progress that has been made in the taste and discernment, which this country applies to industry. I have understood that, for some of the textile fabrics, patterns are now not imported only, but also exported to France in exchange.

p.30 Influence of the war 1793-1815

Nor let us treat this as if it were a matter only of blame to our immediate forefathers, and of commendation to ourselves. It has not, I think, been sufficiently considered, what immense disadvantages were brought upon the country, as respects the application of Fine Art to Industry, by the great Revolutionary War. Not only was the engrossing character of a deadly struggle unfavourable to all such purposes, but our communion with the civilized world was placed under very serious restraint; and we were in great measure excluded from resort to those cities and countries, which possessed in the greatest abundance the examples bequeathed by former excellence. Nor could it be expected, that Kings and Governments, absorbed in a conflict of life and death, and dependent for the means of sustaining it ou enormous aud constant loans, could spare either thought or money from war and its imperious demands, for these, the most pacific among all the purposes of peace. At any rate, I take it to be nearly certain, that, the period of the war was a period of general, and of progressive, depression, and even degradation, in almost every branch of industrial art. Nor is this the less true in substance, because Beauty may have had witnesses here and there, prophesying, as it were, in sackcloth on her behalf. I apprehend that, for example, the fabrics of your own manufacture were, in point of taste and grace, much inferior to what they had been at a former time; that the older factories had in some cases died out, in others, such as Worcester, for instance, they had declined : and that, whereas Wedgwood is said to have exportd five-sixths of what he made, we not only had lost, forty or fifty years ago, any hold such as he had obtained upon the foreign market, but we owed the loss, in part at least, and in great part, to our marked declension in excellence and taste.

p.32 Wedgwood's excellence in the middle sphere

I submit, however, that, considering all which England has done in the sphere of pure Beauty on the one side, and in the sphere of cheap and useful manufacture on the other, it not only is needless, but would be irrational, to suppose that she lies under any radical or incurable incapacity for excelling also in that intermediate sphere, where the two join hands, and where Wedgwood gained the distinctions which have made him, in the language of Mr. Smiles, the "illustrious" Wedgwood. I do not think that Wedgwood should be regarded as a strange phenomenon, no more native to us and ours than a meteoric stone from heaven; as a happy accident, without example, and without return. Rare indeed is the appearance of such men in the history of industry: single perhaps it may have been among ourselves, for whatever the merits of others, such in particular as Mr. Minton, yet I for one should scruple to place any of them in the same class with Wedgwood ; no one is like him, no one, it may almost be said, is even second to him;

but the line on which be moved is a line, on which every one, engaged in manufacture of whatever branch, may move after him, and like him. And, as it is the wisdom of man universally to watch against his besetting errors, and to strengthen himself in his weakest points, so it is the study and following of Wedgwood, and of Wedgwood's principles, which may confidently be recommended to our producers as the specific cure for the specific weakness of English industry.*

Of imagination, fancy, taste, of the highest cultivation in all its forms, this great nation has abundance. Of industry, skill, perseverance, mechanical contrivance, it has a yet larger stock, which overflows our narrow bounds, and floods the world. The one great want is, to bring these two groups of qualities harmoniously together; and this was the peculiar excellence of Wedgwood; his excellence, peculiar in such a degree, as to give his name a place above every other, so far as I know, in the history of British industry, and remarkable, and entitled to fame, even in the history of the industry of the world.

p.35 His commencement of labour

We make our first introduction to Wedgwood about the year 1741, as the youngest of a family of thirteen children, and as put to earn his bread, at eleven years of age, in the trade of his father, and in the branch of a thrower.

Then comes the well-known small-pox : the settling of the dregs of the disease in the lower part of the leg: and the amputation of the limb, rendering him lame for life. It is not often that we have such palpable occasion to record our obligations to the small-pox. But, in the wonderful ways of Providence, that disease, which came to him as a two-fold scourge, was probably the occasion of his subsequent excellence.*

It prevented him from growing up to be the active vigorous English workman, possessed of all his limbs, and knowing light well the use of them; but it put him upon considering whether, as he could not be that, he might not be something else, and something greater. It sent his mind inwards; it drove him to meditate upon the laws and secrets of his art. The result was, that he arrived at a perception and a grasp of them which might, perhaps, have been envied, certainly have been owned, by an Athenian potter. Relentless criticism has long since torn to pieces the old legend of King Numa, receiving in a cavern, from the Nymph Egeria, the laws that were to govern Rome. But no criticism, can shake the record of that illness, and that mutilation of the boy Josiah Wedgwood, which made for him a cavern of his bedroom, and an oracle of his own inquiring, searching, meditative, fruitful mind.

p.37 Summary of his performances

From those early days of suffering, weary perhaps to him as they went by, but bright surely in the retrospect both to him and us, a mark seems at once to have been set upon his career. But those, who would dwell upon his history, have still to deplore that many of the materials are wanting. It is not creditable to his country or his art, that the Life of Wedgwood should still remain unwritten. Here is a man, who, in the well-chosen words of his epitaph, "converted a rude and inconsiderable manufacture into an elegant art, and an important branch of national commerce." Here is a man, who, beginning as it were from zero, and unaided by the national or royal gifts which were found necessary to uphold the glories of Sevres, of Chelsea, and of Dresden, produced works truer, perhaps, to the inexorable laws of art, than the fine fabrics that proceeded from those establishments, and scarcely less attractive to the public taste of not England only, but the world. Here, again, is a man, who found his business cooped up within a narrow valley by the want of even tolerable communications, and who, while he devoted his mind to the lifting that business from meanness, ugliness, and weakness, to the highest excellence of material and form, had surplus energy enough fo take a leading part in great engineering works like the Grand Trunk Canal from the Mersey to the Trent: which made the raw material of his industry abundant and cheap, which supplied a vent for the manufactured article, and which opened for it materially a way to what we may term its conquest of the outer world. Lastly, here is a man who found his country dependent upon others for its supplies of all the finer earthenware, but who, by his single strength, reversed the inclination of the scales, and scattered thickly the productions of his factory over all the breadth of the continent of Europe. There has been placed in my hands, this very morning, a testimony to the extraordinary performance of Wedgwood in this respect, which is couched in such terms, that I might have scrupled to accept or quote them, had they been due to the partial pen of a countryman. But the witness is a contemporary Frenchman, M. Faujas Saint Fond; who, in his Travels in England, writes as follows respecting Wedgwood's ware:— "Its excellent workmanship; its solidity ; the advantage which it possesses of standing the action of the fire; its fine glaze, impenetrable to acids; the beauty, convenience, and variety of its forms, and its moderate price, have created a commerce so active, and so universal, that in travelling from Paris to St. Petersburg, from Amsterdam to the furthest point of Sweden, from Dunkirk to the southern extremity of France, one is served at every inn from English earthenware. The same fine article adorns the tables of Spain, Portugal, and Italy; it provides the cargoes of ships to the East Indies, the West Indies, and America."

p.40 His life only about to be written

Surely it is strange that the life of such a man should, in this "nation of shopkeepers," yet at this date remain unwritten; and I have heard with much pleasure a rumour, which I trust is true, that such a gap in our literature is about to be filled up.

All that we know, however, of the life of Wedgwood seems to be eminently characteristic. We find the works of his earliest youth already beginning to impress a new character upon his trade: a character of what may be called precision and efficiency, combined with taste, and with the best basis of taste, a loving and docile following of nature.*

p.41 His first partnerships

We find him beginning his partnerships when manhood was but just attained, first with Harrison, a fellow-workman, secondly with Whieldon; and the latter business, I believe, was carried on at the exact place where we are now assembled. But, as we might naturally expect in the case of a spirit so energetic and expansive, we find that in each of these cases the bed did not give him room enough to lie on or to turn in; and in 1709, as soon as his articles with Whieldon expire, he escapes from his unequal yoking, and enters into business by himself.

This, however, though a natural, was not a final stage. It was necessary that he, who was the soul, should also be the centre and the head: but it was further necessary that he should surround himself at all points with an efficient staff for a great, varied, and not merely reforming but creative work. Hence he associated himself with Mr. Richard Bentley as a partner; who is stated to have chiefly superintended the London business, but who has credit for having supplied the information, necessary to enable the firm to enter so largely on the handling of classical designs.

p.42 His assistants

Hence he employed Mr. Chisholm as an experimental chemist, and other scientific men in the several departments of the business. Hence his connexion with Flaxman, which has redounded alike to the honour of the one and of the other. It was once the fashion to say that Queen Elizabeth had by no means been proved to be a woman of extraordinary powers, but that she certainly had ministers of vast ability. And in like manner some might be tempted to suspect, when they have seen Wedgwood thus surrounded, that his merit lay chiefly in the choice of instruments and coadjutors, and that to them the main part of the praise is due. What were the respective shares of Bentley and others in the great work of Wedgwood, is a question of interest, on which it may be hoped that we shall soon he more largely informed.

It is plain that, in an enterprise so extended and diversified, there not only may, but must, have been, besides the head, various assistants, perhaps also various workmen, of merit sufficient to claim the honour of separate commemoration. As to the part which belongs to Flaxman, there is little difficulty: notwithstanding the distorting influence of fire, the works of that incomparable designer still in great part speak for themselves. To imitate Homer, Æschylus, or Dante, is scarcely a more arduous task than to imitate the artist by whom they were illustrated. Yet I, for one, cannot accept the doctrine of those, who would have us ascribe to Flaxman the whole merit of the character of Wedgwood's productions, considered as works of art. And this for various reasons.

First, from what we already learn of his earliest efforts, of the labours of his own hands, which evidently indicate an elevated aim, and a force hearing upwards mere handicraft into the region of true plastic Art: as, again, from that remarkable incident, recorded in the history of the Borough of Stoke, when he himself threw the first specimens of the black Etruscan rases, while Bentley turned the lathe.

Secondly, because the very same spirit, which presided in the production of the Portland Or Barberini vase, or of the finest of the purely ornamental plaques, presided also, as the eye still assures us, in the production not only of déjeûners, and other articles of luxury, intended for the rich, but even of the cheap and common wares of the firm. The forms of development were varied, but the whole circle of the manufacture was pervaded by a principle one and the same.

Thirdly, because it is plain that Wedgwood was not only an active, careful, clear-headed, liberal-minded, enterprising man of business, —not only, that is to say, a great manufacturer, but also a great man. He had in him that turn and fashion of true genius, which we may not unfrequently recognise in our Engineers, but which the immediate heads of industry, whether in agriculture, manufactures, or commerce, and whether in this or in other countries, have more rarely exhibited.

p.45 His works in fine art

It would be quite unnecessary to dwell on the excellences of such of the works of Wedgwood, as belong to the region of Fine Art strictly so called, and are not, in the common sense, commodities for use. To these, all the world does justice. Suffice it to say, in general terms, that they may be considered partly its imitations, partly as reproductions, of Greek art. As imitations, they carry us back to the purest source. As reproductions, they are not limited to the province of their originals, but are conceived in the genuine, free, and soaring spirit of that with which they claim relationship. But it is not in happy imitation, it is not in the successful presentation of works of Fine Art. that, as

p.46 He revived the principle of Greek industrial art

I conceive, the specialty of Wedgwood really lies. It is in the resuscitation of a principle; of the principle of Greek art: it is in the perception and grasp of the unity and comprehensiveness of that principle. That principle. I submit, lies, after all, in a severe and perfect propriety ; in the uncompromising adaptation of every material object to its proper end. If that proper end he the presentation of Beauty only, then the production of Beauty is alone regarded; and none bat the highest models of it are accepted. If the proper end be the production of a commodity for use and perishable, then a plural aim is before the designer and producer. The object must first and foremost be adapted to its use as closely as possible: it must be of material as durable as possible; and while it must be of the most moderate cost compatible with the essential aims, it must receive all the beauty which ean be made conducive to, or concordant with, the use. And because this business of harmonizing use and beauty, so easy in the works of nature, is arduous to the frailty of man, it is a business which must be made the object of special and persevering care. To these principles the works of Wedgwood habitually conformed.

p.47 His independance of public aid

He did not in his pursuit of Beauty overlook exchangeable value, or practical usefulness. The first he could not overlook, ibr he had to live by his trade; and it was by the profit, derived from the extended sale of his humbler productions, that he was enabled to bear the risks and charges of his higher works. Commerce did for him, what the King of France did for Sèvres, and the Duke of Cumberland for Chelsea; it found him in funds. And I would venture to say, that the lower works of Wedgwood are every whit as much distinguished by the fineness and accuracy of their adaptation to their uses, as his higher ones by their successful exhibition of the finest art. Take, for instance, his common plates, of the value of I know not how-few, but certainly a very few, pence each. They fit one another as closely as the cards in a pack. At least I, for have, have never seen plates that fit like the plates of Wedgwood, and become one solid mass. Such accuracy of form must, I apprehend, render them much more safe in carriage. Of the excellence of these plates we may take it for a proof that they were largely exported to France, if not elsewhere, that they were there printed or painted with buildings or scenes belonging to the country, and then sent out again as national manufactures.

p.48 His humbler productions

Again, take such a jug its he would manufacture for the washhand-table of a garret. I have seen these, made apparently of the commonest, material used in the trade. But, instead of being built up, like the usual, and much more fashionable, jugs of modem manufacture, in such a shape that a crane could not easily get his neck to bend into them, and that the water can hardly be poured out without risk of spraining the wrist, they are constructed in a simple capacious form of flowing curves, broad at the top, and so well poised that a slight and easy movement of the hand discharges the water.

A round cheese-holder, or dish, again, generally presents in its upper part a flat space, surrounded by a curved rim : but a cheese-holder of Wedgwood's will make itself known by this, that the flat is so dead a flat, and its curve so marked and bold a curve: thus at once furnishing the eye with a line agreeable and well-defined, and affording the utmost available space for the cheese. I feel persuaded that a Wiltshire cheese, if it could speak, would declare itself more comfortable in a dish of Wedgwood's, than in any other dish.

Again, there are certain circular inkstands by Wedgwood, which are described in the twenty-first section of the Catalogue. It sets forth the great care which had been bestowed upon the mechanical arrangement, with a view to the preservation of the pen, and the economical and cleanly use of the ink. The prices are stated at from sixpence to eight shillings, according to size and finish. I have one of these; not however black, like those mentioned in the Catalogue, but of his creamy white ware. I should guess that it must have been published at the price of a shilling, or possibly even less. It carries a slightly recessed upright rectilinear ornament, which agreeably relieves a form other wise somewhat monotonous. But the ornament does not push this inkstand out of its own homely order. It is so tasteful that it would not disgrace a cabinet, but so plain that it would suit a counting-house. It has no pretention ; all Wedgwood's works, from the lowest upwards, abhor pretension.

While he always seems to have in view a standard of excellence indefinitely high, he never falls into extravagance or excess. I do not mean to say that all the wares which proceeded from his furnaces are alike satisfactory; but I am confident that it is easy, even from his cheaper and lower productions, without any reference to the higher, to prove him to have been a man of real genius, thoroughly penetrated with the best principles of art.

p.51 His intermediate productions

I have spoken of Wedgwood's cheapest, and also of his costliest, productions. Let me now say a word on those which are intermediate. Of these, some appear to me to be absolutely faultless in their kind: and to exhibit, as happily as the remains of the best Greek art, both the mode and the degree in which beauty and convenience may be made to coalesce in articles of manufacture. I have a dejeuner, nearly slate-coloured, of the ware which I believe is called jasper ware. This seems to me a perfect model of workmanship and taste, The tray is a short oval, extremely light, with a surface soft as an infant's flesh to the touch, and having for ornament a scroll of white riband, very graceful in its folds, and shaded with partial transparency. The detached pieces have a ribbed surface, and a similar scroll reappears, while for their principal ornament they are dotted with white quatrefoils. These quatrefoils are delicately adjusted in size to the varying circumferences: and are executed both with a true feeling of nature, and with a precision that would scarcely do discredit to a jeweller.

Enough, however, of observations on particular specimens of your great master's work. But let me hazard yet a few words on the general qualities of his business and his productions. It seems plain that, though uneducated in youth for any purpose of art, he contrived to educate himself amidst the busy scenes of life. His treatise on the pyrometer shows that he had studied, or at any rate acquired, all the science applicable to his business: his account of the Barberini vase proves, that he had qualified himself to deal personally, and not only through partners or assistants, with the subjects of classical antiquity.

p.53 His view of cheapness

But nothing can be more characteristic of his mind, than the firmness with which, at the close of the Catalogue, the intentions of the firm respecting cheapness of production are declared. He has before explained, as I have already mentioned, that the utmost cheapness can hardly be had along with the highest beauty. He goes on to vindicate his prices, as compared with those of others: and concludes his apology, in terms which do the firm the highest honour, by declaring plainly, " they are determined to give over manufacturing any article, whatsoever it may be, rather than to degrade it." A clear proof, I think, that something, which resembles heroism, has its place in trade. With this bold announcement to the world was combined, within the walls of his factory, that unsparing sacrifice of defective articles, and confinement of his sales to such as were perfect, which down to this day supply the collector, in a multitude of cases, with the test he needs in order to ascertain the genuine work of the master.

p.54 General qualities of his ware

The lightness of Josiah Wedgwood's ware, which is an element not merely of elegance but of safety; the hardness and durability of the bodies; the extraordinary smoothness, and softness to the touch, of the surfaces; their powers of resisting heat and acids; the immense breadth of the field he covered, with the number and variety of his works in point of form, subject, size, and colour—this last particularly as to his vases; his title almost to the paternity * of the art of relief in modern earthenware ; all these are characteristics, which I am satisfied only to name.

p.55 His colours

There are, however, two other points still on my mind; one the prevailing character of his colours; the other his extraordinary merit as a restorer of form in fictile products.

The general character of his colours may perhaps be justly described as a strict sobriety imbibed from, and closely following, the antique. He did not attempt to cover the entire field of porcilain manufacture. That which is perhaps the noblest and most arduous part of all its work, I mean modelling the human figure in the solid, he rarely attempted.*

And we must not look to him for the gay diversity of its colouring and subjects ; for its gliding sometimes so gorgeous and sometimes so delicate; or for the Splendid effects yielded (in particular) by its deep blue grounds. In no instance, known to me, does he indulge in showy colour. He has indeed highly glazed vases in admirable taste and of great effect, but usually, I think, the ground is some variety of green or grey. His eye could not, however, have, been insensible to the attractions of such colouring, as was produced at Sèvres or at Chelsea. When we find a general characteristic, running through the works of a man like Wedgwood, we may safely assume there was a reason for it. Probably or possibly, the reason for the restraint and sobriety of the colouring which he used is to be found not in mere imitation, but in the classical and strict severity of his forms.

p.57 His forms

I hope it will not be thought presumptuous to give utterance to an opinion, that the forms of many among the most costly and splendid vases which were produced at Chelsea, and even at Sèvres, in the last century, were unsatisfactory : sometimes fantastic, often heavy and ungainly, rarely quite successful in harmonising the handles with, the vessel, and upon the whole neither conformable to any strict law of Art, nor worthy of the material, or of the fine colouring, drawing, composition, and gilding, there and elsewhere so often exhibited in the decoration. On comparing the forms of vases produced at those factories with vases of Wedgwood, although these doubtless have also suffered as to their finer proportions from shrinking in the fire, I have felt it for myself impossible to avoid being struck with his superiority, and arriving at an opinion that his lifetime constitutes in modern fictile manufacture little less than a new era as to form. It is hard to avoid conjecturing thaf his eye must have noticed, and must in this respect have condemned, the prevailing fashion, and that he must have formed a deliberate resolution to do what I think unquestionably he did; namely, to exhibit to the world, in this vital particular, a much higher standard of excellence than he found actually in vogue.

p.58 His character

Of the personal character of Wedgwood, in its inner sense, the world has not yet been informed: but none can presume otherwise than well of one, who, in all those aspects which offer themselves to the view of the world, appears to have been admirable. For our present purpose let us consider him only as a master. And this is a matter of more than common interest, at a time when so many of the most eminent firms in the district have, in a manner the most laudable, themselves called the attention of public authority to the condition of their younger labourers, with a view to obtaining the friendly aid of legislative interference for their adequate instruction and protection,*

Indeed we may say, respecting this all-important question of the condition of the people, what we said of the element of beauty in manufacture. The demand for cheapness presses hard upon it: yet nothing, which depresses the moral or physical condition of the people below the standards of Christianity, of sufficiency, and of health, can in the end be cheap.

p.59 Goldsmith's 'Deserted Village'

In the year 1769, when Wedgwood was promoting the Grand Trunk Canal, and building his works and settling his colony at Etruria, Goldsmith published the beautiful poem of the ' Deserted Village,' which he chose with strange caprice to found upon the idle notion that it was the tendency of trade to depopulate the country. "Ill," says he,

Nor does he only mean, that trades ill-regulated may be injurious to health. After describing rural happiness, he begins his lament by the following lines:—

And what is most of all singular is, that he associates this substitution of towns for villages with a decrease in the numbers of the people:—

p.61 Benefits conferred on the district

At any rate, Wedgwood's does not appear to have been one of those baneful arts. Listen to the account, given by Mr. Smiles, of the mode in which Wedgwood thinned mankind :— "From a half-savage, thinly-peopled district of some 7000 persons in 1760, partially employed and ill-remunerated, we find them increased, in the course of some twenty-five years, to about treble the population, abundantly employed, prosperous, and comfortable." *

Nor was this multiplication only, without improvement; for he goes on to quote from John Wesley, who had been pelted at Burslen in 1760, the following remarkable words:— "I returned to Burslem. How is the whole face of the country changed in about twenty years! Since which, inhabitants have continually flowed in from every side. Hence, the wilderness is literally become a fruitful field. Houses, villages, towns, have sprung up; and the country is not more improved than the people." *

It is impossible to conceive a testimony more honourable to Wedgwood; nor can I better conclude these remarks than by uttering the cordial hope that you, his successors, who have during late years earned so much honour for the taste and industry of the country, may profit in all respects more and more effectually by the lessons which your great forerunner has bequeathed you, and may find at least one substantial part of your reward in witnessing around you a thriving and contented, a healthy and a happy population.

|

|

The

Wedgwood Institute details of the Wedgwood Institute, built as a library, museum and art school in 1869. |