Stoke-on-Trent is a short year away from commemorating its centenary as a

federated county borough. In 1910 the separate district administrations of

six principal towns decided to chuck their lot in together and have a go

at being a single-managed local authority.

“For generations the separate towns had shared the common resources of

subterranean mineral wealth and delivered the collective skills of art

and manufacture and talent in retailing and exporting it. In plain

terms it made good sense to pool these resources,” considers

Potteries’ historian Steve Birks.

“But it was a nervous beginning with some of the parties having to

be persuaded kicking and screaming. Nevertheless it was successful –

so successful that after fifteen years the Federated towns were

rewarded by King George V who conferred upon it the status of City

of the Realm.”

|

Stoke-on-Trent is one of only 50 local government districts and civil

parishes in England that have the right to claim city status. It may have

been seen as an upstart alongside such bastions of the Roman Age as Bath

and Chester, or centres of learning like Oxford and Cambridge, or the

religious cities of Canterbury and Winchester, and the major gateways of

international trading Liverpool and Bristol, or reforming municipalities

like Manchester and Birmingham. Nevertheless, Stoke-on-Trent sits proudly

on the list. How it achieved this can be explained by who did what, when,

and how. More importantly does the city’s motto – Vis Unita Fortior

(united strength is stronger) still hold up.

“I can

see that four important basic elements influenced its rise and

subsequent realization in becoming one of the world’s most important

manufacturing centres and its development as an independent society

through social enlargement,” offers Steve. “The first clearly lies in

its mineral assets. The second is the resolve and excellence of the

artisans that dug out the coal, iron and clay and moulded it into a

superior and saleable product. Third is its proximity with natural

marketplaces, in particular Newcastle-under-Lyme which is really the

seventh town. But most important is the quality of civic administrators

both elected and appointed.”

Much of

the key research on North Staffordshire’s municipal constitution was

produced by John Ward his in seminal work, The Borough of Stoke on Trent,

in 1843.

“Ward

wasn’t a local man,” continues Steve. “He was born in Leicestershire in

1781 and became a qualified solicitor. Like many enterprising

prospectors he was attracted to the soaring opportunities of the

Potteries during the Industrial Revolution when many support-industries

settled in the new expanding towns. Ward was 28 when he came to Burslem

in 1809 where he secured the representation of a number of civil

agencies. He became chief constable of the town and a licensing

commissioner. But his interest in local history was his overriding

passion.”

Ward

joined forces with a Manchester printer and schoolteacher name Simeon Shaw

who was teaching at an academy in Northwood Hanley. Shaw was an

antiquarian collector and shared his research with the famous Burslem

potter Enoch Wood who was, in the first decades of the 19th

century, already an established civic leader. A published historian, Shaw

teamed up with John Ward to write a series of articles recording the

history and Parliamentary Union of the Borough of Stoke on Trent from

1832. And it was the ground-breaking Reform Act of 1832 that provided the

spark and the backdrop to this history.

|

“The

1832 Act revised many of the earlier manorial boundaries into

electoral constituencies,” says Potteries’ academic historian Richard

Talbot.

“It

identified eleven existing townships in North Staffordshire –

Tunstall, Burslem. Hanley, Shelton, Penkhull-with-Boothen, Lane End

and Longton, Fenton Vivian, Fenton Culvert; the Hamlet of Sneyd and

the Vill of Rushton. These locations were specific divisions under

the manorial Courts Leet and Courts Baron that implemented and

upheld local feudal and medieval rules. One of these courts sat at

Penkhull every third Thursday in a local farmhouse near the

Greyhound pub. In 1540 the Greyhound became the Manor Courthouse of

the more important Newcastle-under-Lyme from 1558 to 1829. The

building was enlarged in1704 and subsequently reconstructed in 1936

to what we more or less see today.”

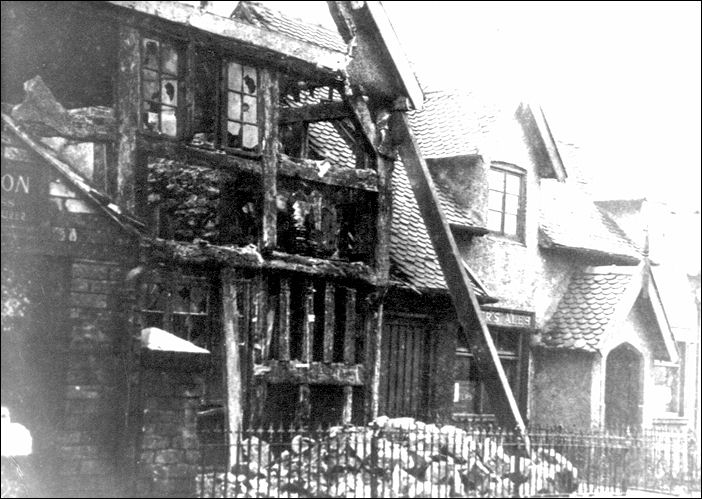

The

Greyhound under reconstruction in 1936 after fire damage

Very

little of the original sixteenth-century oak frame is preserved. But a

stone chimney inside a lounge is unique also a rear timber-framed wing

and a room on the north side.

|

Richard Talbot outside the Greyhound, Penkhull

“Until the Reform Act the district was represented in parliament at county

level,” says Richard.

“The Industrial Revolution had seen many towns grow rapidly from a

collection of villages into decent size communities. Yet they had no

independent parliamentary representation. The Reform Act took the new

industrial towns into consideration by enfranchising all males with

property of a rateable value of £10. It did away with corrupt pocket

boroughs – constituencies with an electorate of fewer than 2000. And it

created 22 new constituencies not previously represented, one of which was

the new borough of Stoke-upon-Trent. It’s first two MP’s were Josiah

Wedgwood II and the Burslem potter John Davenport. Little did they know

then but these were the first steps to Federation.”

click the "contents"

button to get back to the main index