|

The

town of T[unstall], where I was born, is built on a long hillside. It slopes upward from the south to the north, the north standing in close proximity to a mining district, bordering on Cheshire, and the southern part of the town tailing

off towards the town of B[urslem].

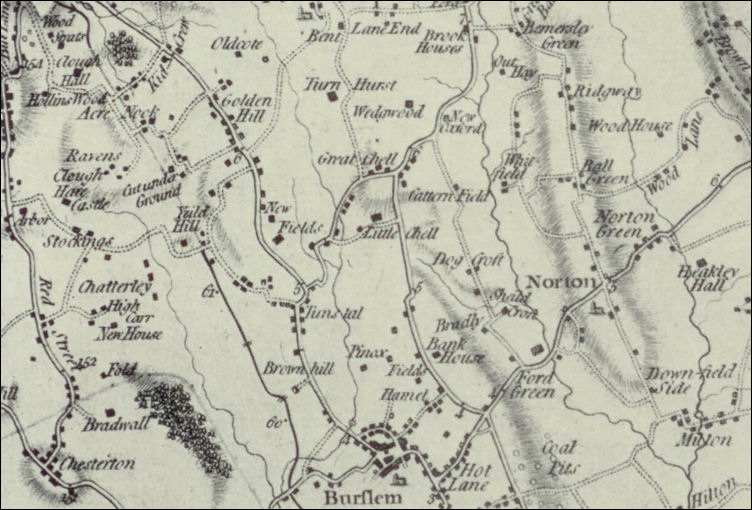

Yates

map of 1775 - showing Tunstall, Burslem, Chatterley

The western side of the town

was the most built upon, though in later days the eastern side has become more occupied. Looking from this western side, there was at that time a little valley, through which a tributary of the Trent ran. I have often caught Jack Sharps in the tiny stream, and gathered buttercups, daisies, and lady flowers on its banks. In spring time the flowers were most abundant in the fields lying in the valley. In the midst of them stood

Chatterly Farm, then a farm of some consequence, as It mainly supplied the town with milk. It was, too, a centre for Sunday wanderings, especially in spring and summer, for the heavy workers of the town, where they got refreshing supplies of milk and curds and whey.

Poor "Billy

Brid" — a half-daft cowboy or cowman lived at the farm.

Who will ever forget his small figure, his half-opened eyes, and his self-possessed merry whistle ? Why he was called " Billy Brid " I never knew, and can only suppose this "dub" was given him owing to his persistent whistling. Birds abounded near the farm, and through the valley, which was uninvaded and as peaceful as Arcadia itself.

On the other side of the

farm, and rolling southward, was a well-wooded hillside, called Braddow Wood in the common speech of the time. This wood was divided by the same common speech into the Big Wood and the Little Wood. The Big Wood was a home of birds and rabbits, strictly watched by two keepers, who lived in cottages, one at each end of the wood.

Bold was the man or boy who strayed off the footpath leading through the wood. Beside the two keepers were two ferocious dogs, their constant companions, and probably no constable in those days, or policeman now, was such a terror to evildoers.

The Little Wood, however, was the most trespassed upon, for birds' nests in summer and for blackberries in autumn. Blackberries then meant not only a luxury, but meant also less butter and less treacle to be used in the poor homes of the people in the town. Children were encouraged, in spite of perils from dogs and keepers, to invade the Little Wood at the proper season. Happy those who came away with their cans full of the precious berries ; but woe to those pursued by keepers and dogs, and whose cans lost their precious treasures in the pursuit.

This pursuing was a brutal business, for little harm could be done by the children in tramping on such rough scrub as the wood contained. But game was sacred then, even rabbits, and rather than these should be disturbed a useful and wholesome fruit was allowed to perish largely on the trees.

This lovely, peaceful, and fruitful valley is now choked with smoke and disfigured by mining and smelting refuse. If Cyclops with his red-handed and red-faced followers had migrated upwards from the dim regions below and settled on the surface amid baleful blazes and shadows, a greater transformation could not have taken place.

Huge mounds of slag and dirt are seen now, filling the valley, burning for years with slow, smoky fires within them. Poor Chatterly Farm stands like a blasted wraith of its once rural buxomness.

The Big Wood is blotched and scarred with heaps of slag in enormous blocks. Where birds once sang in the stillness of its trees, a railway engine now snorts and blows like an o'er-laboured beast, and trucks mangle and jangle with their wheels and couplings. A railway runs through the valley, and it seems a mystery to every observer from the town how the trains find their way through the mound encumbrances which would seem to block the road.

Such is the march of civilisation ! Such is the progress of industry ! And yet people wonder that Mr Ruskin curses these devastations with such passion and with such brilliant invective. Changing Eden to Gehenna may give the outskirts of Gehenna " greater productive power, and maintain a larger

population," but there will always be sentimentalists who will prefer Eden in its simpler and smaller life.

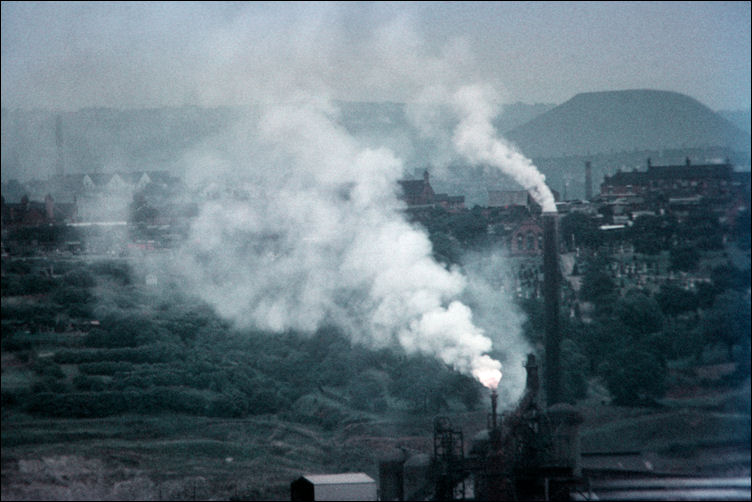

Goldendale

Iron Works

photo: Ken & Joan Davis

"Huge mounds of slag and dirt are seen now, filling the valley, burning for years with slow,

smoky fires within them"

If great populations meant more robust manhood, more of sweet "reasonableness" in all the conditions of life, more of virgin humanity, then they might be preferred. But when industrial population means rural desolation there will always be found those who prefer a poor simplicity of life to the rich drudgery and foulness of " growing industries." But when I began this chapter, I did not intend to say so much about the surroundings of my native town. I was intent rather on describing its social condition, and must ask to be excused this digression which has come as the expression of a long pent-up sorrow and indignation.

My first employer was called " Owd Neddy " in whispers when he was near, and in fierce contempt when he was far away. In one thing he was typical of employers of the town, who were few, and this in his absolute indifference as to the condition of the

people, with one or two exceptions.

Beerhouses

abounded, drunkenness was a prevailing vice, making the common and chronic poverty more bitter and ghastly—beerhouses for the common herd, but, the hotel and the " Lamb " were for the gentlemen. " Owd Neddy " was one of the gentlemen, and though he could have indulged himself to his heart's content at home, yet his vanity demanded a social vent, so he was often found at the hotel or the Lamb on the week evenings.

Of course, many of his poor helots were working while he was quaffing his social glass, or else that glass would not have been so inspiring.

These gentlemen exhibited their inferior tastes, especially at the fag end of an annual Wake. When the bulk of the people had spent their money in fun and fury, and in riotous living, these gentry and publicans would subscribe for sack-races, for eating boiling porridge, for eating hot rolls dipped in treacle, suspended on a line of string, eight or ten competitors for a prize standing with gaping mouths, swaying bodies, and their hands tied behind their backs. Then as dusk came on, and the excitement flagged, these " gentlemen," with their glasses of whisky, sitting at the second-storey windows of the hotel or the " Lamb," threw shovelfuls of hot coppers among the frantic crowds. And so the revelry and devilry continued till darkness and exhaustion dispersed the silly and misguided multitude.

This was the sort of life I witnessed yearly in the early

[1840's] forties.

We had only two constables in the town then, and they were both cobblers as well as constables. The time of bobbies was not yet come. They always stuck to their " last" till they were sent for, whenever their was a row or fight. Perhaps they had less to do with the " last" on Monday, for this was the day when the idle saint got most notice.

Colliers and potters rarely worked much on Monday, and, with drink plenteously imbibed, free tights were very common. Pugilism and dog-fighting were then in much favour, these succeeding the cock-fighting of a previous

generation.

In every street where there was a beershop, there would probably be a couple of men stripped to the waist, pounding at each other in regular fisticuff order, till they battered each other black and red, or else a couple of bulldogs would be devouring each other amid a howling ring of brutal men. Sometimes the women would scream at these sights, and the constable might hear them, or some women would run to tell him what was going on. If not engaged elsewhere, he would come hurriedly, not with the modern bobby pace, and as soon as he was seen there was a cry raised, "The constable is coming."

That cry never failed to disperse a crowd. Fighting men would pick up their clothes and run as if for life. Backers of dogs would rush the mangled animals away or carry them in their arms. There was a potency in the word " constable " which I have never seen in the word policeman, But we live in progressive times.

I said the cry of " Constable ! " never failed to disperse a crowd, but I saw it do so once. There was a riot among the colliers. This had sprung from a strike. These men had marched to a colliery with the purpose of destroying whatever they could touch on the pit bank. While engaged in this work, a cry came that "the constable was coming." And so he did, and expecting, as usual, that the crowd would disperse, he boldly ran into the thick of it. But nobody gave way. Nobody was afraid.

The men were too numerous and too grimly in earnest, and so when the constable attempted to hinder their destructive work, two or three of the men seized him and carried him to a large water pit, and threw him in as if he had been a dog. Doglike, the poor constable tried to swim to the bank. I stood on that bank full of curiosity and fear, and when the constable was coming to the side a collier got a rail and shoved him back. This cruel treatment was continued till the poor fellow was nearly exhausted, and as drowning was a near issue, a humane cry of protest was raised. The brutal collier threw down his rail, and the nearly drowned constable was allowed to creep out and crawl off home. The constable away, the work of destruction was completed. Everything destroyable on the pit bank and in the engine-house was destroyed.

Night fell upon the scene of havoc, and then the roaring, savage multitude dispersed. That was the end of it, for no arrests had been made, and no witnesses were forthcoming. Strikes in those days were sternly brutal outbursts, only equalled by the merciless tyranny and cruelty of those who

provoked them.

Writing of this matter of strikes, reminds me of a trades-union meeting I once attended before I was ten years old. How I got to that meeting I have quite forgotten, as I have forgotten how I got to the pit bank riot, but the meeting itself remains a fixed memory. I don't remember the language, but I have never forgotten the sentiments expressed. The meeting was held in the club-room of a public-house. Perhaps about a hundred men were present. The door, I know, was locked, for such a meeting was then illegal.

The unjust restraint gave fierceness to the tone of the speeches, and led to loud declamation against the tyrant rulers of the country.

The principal speaker was the editor of

The Potters Examiner. He was a man who had espoused the cause of his fellow-workmen, and so got advanced to this responsible position. He was a vivid and rousing writer, and fluent and fierce speaker. On this particular night he stood on a table to address his audience. The men were pale, and had an exhausted look before the speech was delivered, for most of them had worked twelve to fourteen hours that day, and probably not one of them but had felt the pangs of hunger.

But the speech soon changed the colour of their faces. Every drop of blood they had seemed to rush into their faces. Their exhaustion disappeared with startling swiftness. Flushed faces were seen everywhere, and wild demonstrations of approval of the speech came in quick response to its telling points. References were made to the men's poverty, the wretchedness of their homes, the want and sickness of their wives and children.

These were contrasted, with awful emphasis, with the well-fed tyranny they had to endure and support. Luxurious homes filled with light and plenty and music were contrasted with the hovels in which they lived, often fireless, but for the cinders picked from the cinder heaps of the pot banks, their children crying for food, and their wives groaning in their helplessness to relieve their wants.

Their manhood, their rights were appealed to ; their God-given rights and the callousness and indifference of the Church were denounced in words that might have been dipped in gall.

I remember well the aching tumult in my own heart after this meeting, the sense of a malignant confusion of all things. Yet I remember, too, the flowers in the valley only a few hundred yards away from that throbbing centre of passion.

I thought also of the singing of the birds in Braddow Wood, but here were men yelling with hate of those they regarded as their oppressors. I knew these things meant two different worlds—one belonging to the God and Father, about whom I read every Sunday in the Sunday school ; and the other world, belonging to rich men, to manufacturers, to mine-owners, to squires and nobles, and all kinds of men in authority.

These I supposed made the world of men what it was, through sheer badness in treatment of all who had to work. " It was a childish ignorance," but it served to fire my heart with hatred towards all who were well-to-do.

The editor finished his speech hoarse and exhausted. His wearied and half-famished hearers were exhausted too. After a short and feverish sleep, these wretches would have to be on their way to work by five o'clock next morning. Through such ploughing and sowing, wet with tears and tilled with blood, we have come to the better harvests of organised labour in these days.

Those pale-faced workers have vanished, their storms of passion sobbed themselves out beneath the stillness of the untroubled stars, but "their

works do follow them." We glibly talk of "better times," but this hurrying and superficial generation seldom thinks that these times are richer for the struggles and blood of those who went before them, as the early harvests of the plains of Waterloo were said to be richer after the carnage of the great battle fought there.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()