|

One of the earliest examples of social engineering in the Potteries

can be found in Stoke. During the 1820s, the architect Henry Ward was

commissioned by the church with a view to attracting wealthier

residents to Stoke. Ward designed an attractive terrace in Tudor

Gothic fronting onto St Peter’s Churchyard, utilising yellow brick and

stone dressings beneath Welsh slate roofs. Just five of the terraced

houses remain following the construction of the A500, and are no

longer in residential use, now being used as town centre office

accommodation.

2-6 Brook Street, Stoke

3-4

Brook

Street, Stoke

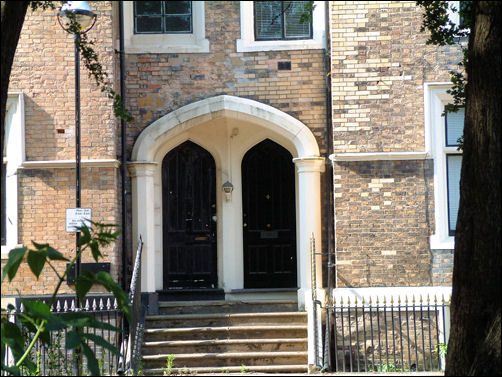

door detail on the houses in

Brook

Street

1 Brook Street followed later in 1867, to a similar style and building

materials. As with the rest of Brook Street, number 1 started life as

a dwelling only to become office accommodation, becoming home of the

National and Provincial Bank. Things have come full circle, with 1

Brook Street being advertised as a residential development

opportunity.

1 Brook Street, Stoke

|

Henry Ward repeated his trick from Brook Street in the development of

the Pinfold Estate in Shelton for the Caldon Place Building Society in

1852. Ward produced a masterplan for a 10½ acre site to the east of

Howard Place and to the north of the Caldon Canal, and a series of

four streets (what are now Norfolk Street, Chatham Street, Wellesley

Street, and Richmond Terrace) were laid out at right angles from Snow

Hill and Howard Place.

Ward’s influence on the development of the estate is evident (some of

the terraced housing has all the hallmarks of Ward’s work on Brook

Street, but on a smaller scale), though another prominent local

architect, Robert Scrivener (whose home and offices were both local)

had a greater influence.

Scrivener’s home is amongst a series of grand villas along College

Road, built from distinctive buff coloured brickwork with a large,

spectacular semi-circular bay of ornate stonework, reflecting both the

wealth and design flair of its owner, whilst his offices were on the

corner of Wellesley Street, and ironically have now been converted to

flats. Wellesley Street is also unusual in that it contains a series

of three storey terraces, which were a rarity in the city at the time.

Terraced housing, Wellesley Street, Shelton

Window detail

Robert Scrivener’s

Offices

(now converted to residential accommodation)

Robert Scrivener’s Villa, College Road, Shelton

Richmond Terrace is

one of the finest terraces in Shelton, and indeed the city. The

terrace has a symmetrical ornate frontage reflecting the gables of the

nearby Flower Pot Hotel. Ornamental brick detailing above window and

door openings help to give the street its distinctive feel.

Richmond Terrace,

Shelton

Detail, Richmond

Terrace |

Many other fine streets of

terraced housing exist throughout the Potteries. As well as the

Wellesley Street area of Shelton some fine examples of the terrace can

also be found to the west of Snow Hill. There is much talk today of

town centre living, and the six towns of the Potteries boasts some

excellent streets, for example Price Street in Burslem, Gilman Street

and the Jasper Street area in Hanley. I have already described some of

the fine housing in the Fenton area, whilst the Dresden and Normacot

areas of Longton are worthy of further discussion (see below).

Higher quality housing, particularly

housing occupied by factory owners, was often away from the inner

urban areas, or else was developed to capitalise on key environmental

assets. One of the finest examples of higher quality housing can be

found in the village of Hartshill, where Josiah Spode built his

glorious home, The Mount.

The Mount

photo: July 2006 © Mr Clive Shenton

Built in 1803 in brick and ashlar with a

spectacular domed main entrance, The Mount was clearly designed to

reflect its owners’ wealth and status. The selection of Spode’s site

is of interest: close enough to his china works in Stoke, yet its

hillside spot ensured that Spode and his family were away from the

choking pollution of the towns and urban areas that his workers had to

cope with. The Mount was subsequently used as a school for the deaf

and blind, and since 2003 – the year of the Mount’s 200th

birthday – it was opened as the Willows Primary School by the Spode

company’s managing director.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()