![]()

|

|

|

|

|

Stoke-on-Trent - photo of the week |

Advert of the Week

Potworks of the Week

The

Outcasts - Trentham Gardens

Commemorative earthenware mug prduced for

the Trentham Outcasts

Outcasts -

First Aniversary

August 1939 - August 1940

photos: Richard Moore

(his aunt was with Midland Bank when they moved to Trentham)

Trentham - August 1940

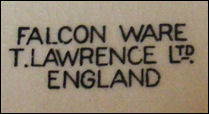

The mug was produced by T. Lawrence Ltd

as part of their Falcon Ware range

It was unusual for commemorative ware to allowed

to be produced during the war period

|

Commemorative earthenware

ashtray prduced for the Trentham Outcasts

Outcasts -

Second Aniversary

August 1940 - August 1941

Trentham 1941

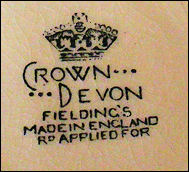

The ashtray was produced by S. Fielding & Co Ltd

as part of their Crown Devon Ware range

| Colette

Warbrook talks to a woman who found herself thrust into the world of

city banking as a teenager

For many, the ballroom at Trentham Gardens is associated with memories of nights spent spinning around the dance floor with a partner. But others will relate it to the sound of banking machines and mail being sorted by industrious workers. In 1939, bombing forced the Central Clearing House to be evacuated from London to Trentham. Ruth Shaw, of Werburgh Drive, Trentham, started her first job there soon after the clearing house arrived and was a member of staff until it returned to London. "It was a lovely job in beautiful surroundings," remembers the 86-year-old. "All the banks were installed in the ballroom.

In the beginning, most of the staff were brought from London and moved in with people in the Trentham area. "They called themselves 'the outcasts'," says Ruth, who lived in Norton at the time, "and from 1940 onwards a news magazine was published, called Outcast Observer. "Gradually more local people were employed and I was probably among the first batch to work there." Each morning sacks of cheques would arrive to be sorted, totalled, balanced and recorded. "The recording was done by a Recordak machine," she explains. "The cheques had to be fed into it singly, then photographed, resorted and mailed out. "We were served a free cooked meal each lunchtime," continues Ruth, "and there was a bar in the dining room. "I remember one occasion when news came through that the Allies had entered Paris. A French lady, who worked in one of the banks, climbed on a table and sang La Marseillaise, with tears streaming down her face." While working at the clearing house, Ruth's future husband, Arthur, was transferred to the nearby forces' convalescent camp. "He served in a tank regiment in the Army," she says, "and he was wounded, possibly by a booby trap, while crossing the Rhine." Ruth and Arthur, now aged 85, married in 1945 and have two children, nine grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. "It was quite a sad day when the banks returned to London," she adds. "Most of my friends went to London as well, but I didn't go." Sentinel Newspaper July 18 2009 |

|

Trentham — A Teenager’s Memories by Estelle Davies I was 17 when the War started, working at the Stoke branch of Barclays Bank and living in Trent Vale (in the same street as the footballer Stanley Matthews as it happens, although I’m not a big football fan). I applied for war work, I’d have liked to have joined the Wrens, but they would not take me as I was in a reserved occupation. I had to carry on working at the bank and do firewatching instead. After the air attacks on London it was decided to move the Bank of England out of the capital for safety, I think it was in 1940. The Bank was based in the ballroom at Trentham Gardens, former home of the Duke of Sutherland. All the major clearing banks had staff based there, and I was transferred to the Barclays section. Each bank had its own section in the ballroom and the foreign section was on the stage.

They are mentioned in most of the books and articles written about Trentham during the war but it seems to be forgotten that not all the staff were Londoners, there were local people there as well. I didn’t mix with them much, we hadn’t a lot in common and I was busy at home keeping house for my father with my two sisters. I had to lay the coal fire before I left in the morning so it could be lit in the evening, help shop, cook and clean so I did not have much time for going out. My Mam had died in 1932, my other sister was married and two of my brothers were doing war work in factories, Norman making tyres at Good Year and Denis making wiring harnesses and aeroplane parts at Rist’s. My other brother was in the RAF and was killed in 1943. We never found out the details until recently as it was all top secret of course, but he was in 138 Squadron, they flew out of Tempsford airfield on missions dropping agents and supplies in occupied France. His plane was shot down in August 1943 and all seven of the crew were killed, five died immediately and Willie and another man died within a couple of days. They are all buried in Normandy, in Ercocei and Bernay. My daughters have been to Willie’s grave and laid a wreath on behalf of the family. We also found out that the squadron flew on nine missions during the same moon period in August, all returned safely except the one my brother was on. My father never really got over his death. I usually walked to and from work, it took about half an hour each way, but it was better than waiting for a bus in the cold and saved bus fare too. The buses were often full with other workers when they did come, and I was also worried about missing my stop in the blackout, there were no street signs, lights or shop signs to give a clue where you were, and the bus just had a little blue light on inside.

The gardens and grounds of the hall are very big and lots of other groups used them. The French were there, I believe they arrived after Dunkirk and were visited on one occasion by a small French man. I found out later this was General de Gaulle. There were also prisoners of war camped there, Italian I think, with possibly some Germans. I used to see them going out in lorries as I walked to work, going to farms and woods around the area to work. I always felt so sorry for them, they did not look like an enemy, just young lads like my own brothers. We had air raid practices at work. There were shelters in the grounds and when the siren went we had to first ‘sheet up’ our work then open the big French windows and go to the shelters (taking our gas masks of course) until the ‘all clear’ sounded. We had quite a few warnings as German bombers were trying to find the steelworks at Shelton Bar and the munitions factory at Swynnerton. They hit the area round the Bar a few times but never found Swynnerton as all the buildings were camouflaged and made to look like farm buildings from the air. The ‘sheet’ we had to use was a piece of canvas or tarpaulin-like material nailed to the underside of one end of the desk. The other end was nailed to a stick around which the material was rolled, this was then hooked under the desk. When the siren went you grabbed the roll and threw it right over the desk so the stick hung down the other side and kept the material tight, which stopped all the papers on the desk from blowing away when the French windows were opened. If the cheques had gone everywhere it would have taken days to sort out the mess, and they could have fallen into enemy hands which was a security risk. I presume all offices had such an arrangement, I saw a desk in the museum in Churchill’s Bunker in London with exactly the same thing on it recently. I stayed at Trentham until the end of the war when I was offered the chance to go to London and work at Barclays Head Office in Lombard Street, they were short of men as so many of the lads had not returned from the war. In those days Lombard Street had rubber cobblestones to deaden the noise from horses’ hooves and vehicles so as not to disturb the staff in the offices. It was very exciting to go as I’d never been to London before, or been away from home except to boarding school. London was badly damaged from the blitz but I enjoyed my stay there. I lived in a hostel in Russell Square with the other girls, one incident that sticks in my mind was enjoying raspberry jam for tea until someone noticed that the pips had legs — some ants had crawled into the jam while it was in the kitchen and we had been eating them! I might have stayed in London for ever but my father died suddenly and I came home to help my sisters keep house. This turned out to be a good thing in the end as I met my future husband at the Barclays branch in Leek where I was sent on my return! Estelle Skinner (née Davies) 'WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar'

|