|

It’s an interesting town Kidsgrove filled with interesting people..

There was once an odd-looking man

who, in Edwardian times, used to follow the fairgrounds around North Staffordshire during Wakes Week. No one knew his proper name so people called him Joe Tash because of his remarkably long waxed moustache. Joe would turn up on the day the fair arrived in the town and erect a wooden stand that was not much more than a plain board with a series of holes cut through. These apertures were large enough for a man’s protruding head and from a distance of fifteen paces a basket of wooden balls was set up inviting revellers to throw at the head of Joe Tash when his face popped through the holes. Joe was a wandering showman who went under the name of ‘The Human Target.’ A penny for three throws and if a ball struck the target Joe would pay out sixpence to the lucky winner. It was not surprising that there were plenty of takers but they always missed. Joe was exceptional at spotting the on-target ball and quick as a flash he’d withdraw his head and stick his grinning face through an adjacent hole – ‘missed!’ he’d laugh.

One wakes week when the fair was at Kidsgrove an unknown cricketer from the local club pinned Joe down with three balls delivered with unusually fast left handed googlies. The bleeding and concussed Joe packed up his stall and was never seen in these parts again. He apparently moved to Walsall where he set up a show called ‘Joe’s Dancing Ducks,’ promoted as the eighth wonder of the world – ‘famous ducks that have danced before the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York’ omitting, of course, that the Prince and the Duke were in fact public houses.

Joe Tash moved about hitching lifts on canal barges and he was not alone in this dangerous form of expeditionary travel for even at the beginning of the 20th century many people travelled by canal boat. There is the famous story of the terrible murder of a young woman who hitched a lift through Harecastle Tunnel. Having set off in the company of three boatmen she was robbed and somehow done to death in the dark, watery subway. Her headless corpse was later discovered but her ghost, known far and wide as the Kidsgrove Buggut, forever haunts the tunnel’s Kidsgrove entrance. Then there’s the story of the ‘Black Dog’ seen on numerous occasions since 1860 roaming around Lower Ash, through Clough Hall and Boathorse Road.

Kidsgrove is full of quirky

stories, most very well documented, and inhabited by people who act with unconventional behaviour. It is a place where no one seems to be in charge – where management and influence resides in the hands of outsiders. Resident, former mayor and past leader of the parish council, John Lockett, entirely agrees.

“On the political stage I suppose you could say control in Kidsgrove is itinerant. Nobody is ever certain who’s running the show and we always seem to be at the awkward end of parliamentary boundary changes. For a start we have a parish council that seemingly stands alone, but the civic administration is controlled from Newcastle. For parliamentary purposes though Kidsgrove comes under Staffordshire Moorlands. In 1983 the town was transferred to Stoke on Trent North. Ten years later we were moved back to the Moorlands and now a review has been concluded that half of us will go back into Stoke on Trent and the other half will stay with Staffordshire Moorlands. But we will still come under the local authority of Newcastle.” Eh, what! Just run that past me again John. “Bewildering isn’t it?” he laughs.

During an 18 year period Kidsgrove’s electorate has been represented by three different MPs. “It is confusing,” says John, “and if you ask people who their MP is they will mostly answer Joan Walley. But of course it’s Charlotte Atkins. After John Forrester Joan used to be the MP then ….” That’s OK John, I say making an excuse to leave – I’ll catch you later.

In Kidsgove’s Market Street I was surprised to find that six out of ten shoppers supported John Lockett’s observation with one elderly visitor to the local Kwik Save brusquely responding to my question, who is your local MP then – “Erm, it’s Jean Woolley isn’t it?”

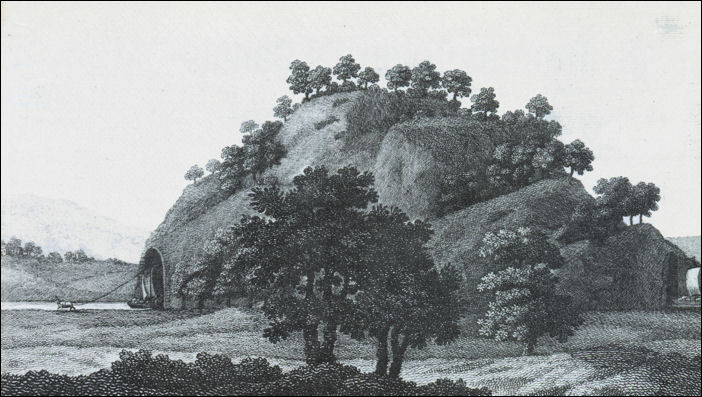

A fanciful contemporary

(1785) print of Harecastle tunnel

There’s not a lot recorded about Kidsgrove’s early

history. Like everywhere else, seemingly, the land was owned by the Audley family and you can easily imagine the way it once looked through the thick woodlands that climb to Goldenhill, a remnant of the great Lyme forest that stretched across the North West, a forest that made North Staffordshire rich in coal. Because of its sharp undulations most travellers preferred to travel around rather than climb the steep hills that surround modern Kidsgrove.

In 1777 the Trent and Mersey canal was opened and with it that most famous wonder of the Industrial Revolution – Harecastle Tunnel. This was James Brindley’s invention made possible by the wealth of rich industrialists, the influence of Josiah Wedgwood and the lives of thousands of labouring navigators – the navvies. It is a mile and three-quarters long and as straight as an arrow. It took eleven years to complete with shafts being bored to a depth of 240 feet. So many lives were broken under this construction that it was known, to those who worked on it, as Heartbreak Hill.

Once the canal was opened the town of Kidsgrove mushroomed, although until the 20th century it was little more than the Market Street and Liverpool Road. As iron, coal and rail arrived new streets were opened and the community settled. The railway station provides and important rail junction carrying the main line from London to Manchester as well as the North Staffs link to Crewe and the Potteries’ Loop Line once ended here. Most heavy industry has departed now but the development of housing on industrial land has left Kidsgrove a dormitory town with a population pushing 26,000.

Loop Line looking to the

back of Market street, Kidsgrove - where the station formerly stood

photo: The Sentinel

Newspaper

Victoria Hall, Kidsgrove

The oldest part of the district is Market Street. “It’s round the back,” one person explains giving me vague northerly directions with his head as I stand in front of the quaintly decorated Victoria Hall. I half expect a cuckoo to spring out of the clock tower, for all the world it looks just like Swiss clock.

But Market Street has a charm that is lacking in most Potteries’ towns even though the terraced houses and former shops and pubs on one side have been completely demolished and replaced by a supermarket and a car park. The side of the street that remains nevertheless contains all anyone could wish for in amenities. A barber’s shop, greengrocers, butcher, laundrette, photographer and a comical-supply company that deals in party stuff hiring out bouncy castles, face painters and giant blow-up sumo wrestlers.

I call at Noah’s Ark pet shop where I meet Janet, one of the new owners, and her assistant, Anna. Peter and Janet Herbert have only just taken over the shop but I’m lucky, the previous owners have just that day popped in to see how things are going. Malcolm and Patricia Thacker recently retired having been looking after and selling pets and pet stuff here for 25 years. And they just happen to be Janet’s parents – so this relationship no doubt preserves the family business for at least another 25 years.

“We’ve seen quite a few changes over the last generation,” says Malcolm. “We took over from Mrs Heath’s DIY and fishing tackle shop. Everybody will remember Mrs Heath.”

“But everybody will remember Gracie’s chemist on the corner below,” joins in Patricia. Certainly their daughter remembers Mr Gracie’s shop.

“It was filled with glass display cabinets and those old bottles with obscure medicines with Latin names that could mean anything,” says Janet. “And on the back shelves were dozens of little wooden drawers containing potions and cures,” adds Patricia. “If there was something wrong with you, poorly or ill, it was always – ‘go round to Mr Gracie’s and he’ll give you something for it,” appends Malcolm.

By now the whole family is at it, chattering around me reminiscing excitedly obviously pleased I’d come by, all that is except Anna, age sixteen, who is far too young to remember old Kidsgrove. The telephone interrupts us rudely. It was Peter over at his other business. Janet insists I take the phone and speak to Peter.

“I love it at Kidsgrove,” he enthuses over the phone as his wife, his mother-in-law and father-in-law continued to rattle on lost in a world that once was – well different. Anna, meanwhile, smiles tolerantly.

“Market Street has a lot of potential and there are some very good businesses here,” says Peter over the phone. “I mean the town is expanding all the time with new residents. We’re just on the fringes of everywhere and I really think the council should invest more, after all they do own quite a lot of the business premises.”

Peter ends the conversation – he has a customer. And I try to interrupt the conversation in Kidsgrove’s Noah’s Ark which has now captured and involved several other of customers in the conversation about old times and which shop was once owned by which trader. It’s time to go. But before I do I wonder whether anybody could identify the big building set between tiny shops up the road?

“Oh that’s the chapel,” Malcolm and Patricia replied in unison. They usher me into the street; Janet follows and two or three of their customers as well. “It was chapel years ago but since then it was converted into Kidsgrove’s first supermarket. Do you remember Cee N Cee?” asks Malcolm. I leave them standing at the edge of the pavement in thrall to their memories

It’s an interesting town Kidsgrove filled with interesting people who insist they want you

to stay. I promised myself I’d return soon.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()

![]()