|

The summer’s sporting orgy

may well have provided a boost to the economy, but the construction industry continues to stutter. In a bid to kick-start building, the Government has looked to do away with ‘unnecessary red tape’ (typical Tory emotional bullshit), and have introduced streamlined planning guidance, a new growth and infrastructure bill (which includes proposals to allow developers to avoid submitting planning applications to local authorities – so much for localism), and they are now proposing to trash Building Regulations and do away design guidelines.

The tactic is clear: the Tories are clearly aiming to get the construction industry moving and provide a huge shot in the arm to the economy in the run-up to the next General Election. These are big mistakes, and will do nothing to tackle the fundamental problems. Firstly, the biggest problem is the availability of finance.

Despite being bailed out by billions and billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money, the banking industry is not lending, and is instead hoarding cash, though it still finds the means to handsomely reward its Chief Executives and other high-flyers for repeated failures.

A guy called Stephen Stone doesn’t think that butchering standards and regulations will help. He should know, he’s the Chief Executive of Crest Nicholson, one of the country’s leading developers. Secondly, this incredibly short-term approach will simply store up problems for the future.

Mr Stone believes that the construction industry should be aspiring to build things that last for at least a hundred years: this is extremely laudable, and a lowering of standards will not help to achieve such a goal. Over the past decade, North Staffordshire and other industrial areas have seen much clearance through the discredited Housing Market Renewal programme. These clearance programmes focused on clearing terraced housing stock and poor social housing. Will a splurge of housebuilding to lower standards lead to future clearance programmes? That is an interesting question for Messrs. Cameron, Osborne, Pickles, Prisk and Boles to consider.

They may also wish to consider a statement from the great Sir Clough Williams-Ellis: “good design is good business”.

As the construction industry continues to struggle, certain players have returned to serious profit. Redrow has recently posted positive results, whilst Barratt announced an increase in profits of some 129%. Another of the industry’s Big Boys, St Modwen, has also started to recover.

St Modwen are synonymous with North

Staffordshire. Ever since the company’s first major development in the area – their monstrous redevelopment of the Garden Festival site, the highly originally monikered Festival Park – St Modwen have had the Potteries in a headlock. The company has a virtual monopoly on the city’s better brownfield development sites, thanks in part to its joint venture with the City Council, Stoke-on-Trent Regeneration Ltd.

This cannot be healthy for the city. St Modwen has effectively land-banked many of the Potteries’ prime development sites, and so coupled with the poor economic climate over the past few years, this has led to a negative impact on the city.

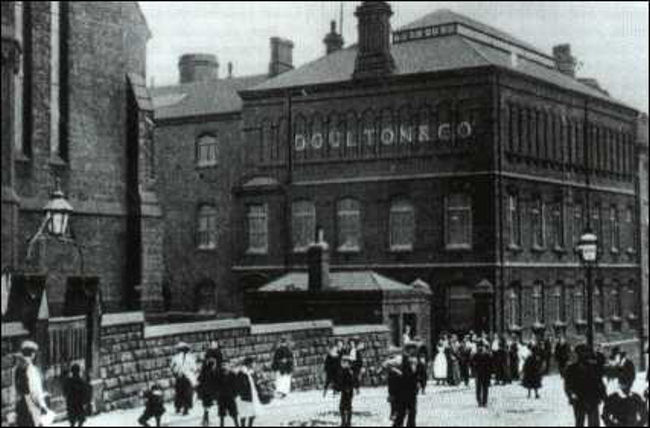

One of the sites caught in the St Modwen headlock is the Nile Street Works in Burslem, the former home of Royal Doulton.

The Nile Street Works has a long history, being built on the site of one of Burslem’s early potteries, with historic trade directories indicating that John Cormie was operating at the works in 1834. Cormie died in 1854, and by 1860, local potters Pinder, Bourne and Hope had relocated to the Nile Street Works in order to manufacture earthenware.

However, just two years later, John Hope left the partnership to continue working at the nearby Fountain Place Works, with a new outfit – Pinder, Bourne and Co. – taking on the Nile Street operations. In 1877, a London-based potter – Henry Doulton – arrived in the Mother Town to take on the Nile Street Works.

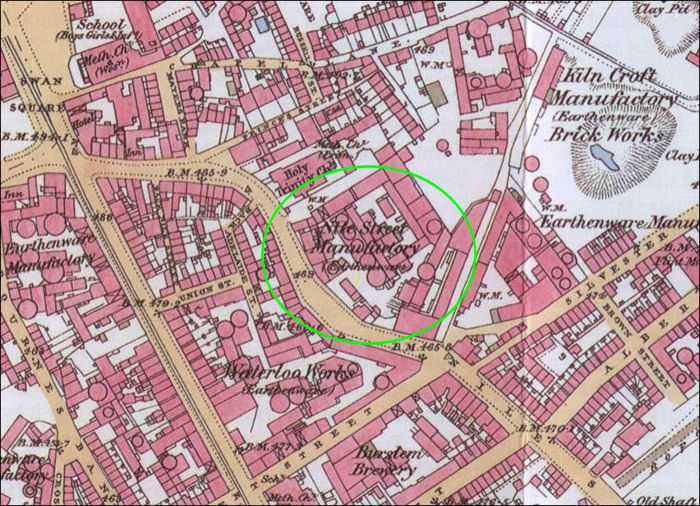

1898

map of Nile Street area and the works

Henry Doulton was born in Vauxhall, and was the second of the eight children of John Doulton, who became a partner in a pottery business in 1815 alongside Martha Jones and John Watts, and the company specialised in stoneware articles.

Henry was the most academic of the Doulton children, and was educated for two years at the University College school, where he developed a passion for art and literature. It seemed that Henry would not join the family business, with his father believing that he would be heading for a profession. However, in 1835, Henry Doulton joined the firm.

Henry took a deep interest in the business, and was constantly experimenting and testing new ideas. One of his first innovations was to produce high-quality enamel glazes, and in 1846, he opened a pipe works in Lambeth, where he went on to produce the sanitary appliances and drainage products which contributed to the company’s growth and fame. Doulton married his wife Sarah in 1849, and they went on to have three children – Sarah Lillian, Henry Lewis, and Katherine Duneau. In 1853, the company took the Doulton name.

By 1870, Henry Doulton once more began to develop new and fresh products. Harnessing the skills of students based at the Lambeth School of Art, he went on to produce ‘art pottery’, showcasing his new wares over the pond in Philadelphia at the 1876 Centennial Exposition. If 1876 proved to be a busy year for Doulton, 1877 proved even more so: Doulton opened his factory at the Nile Street Works in Burslem, and was also knighted. Following the Paris Exhibition of 1878, the French made Sir Henry a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, and he received a further honour in 1885, when the Royal Society of Arts awarded him the Albert Medal.

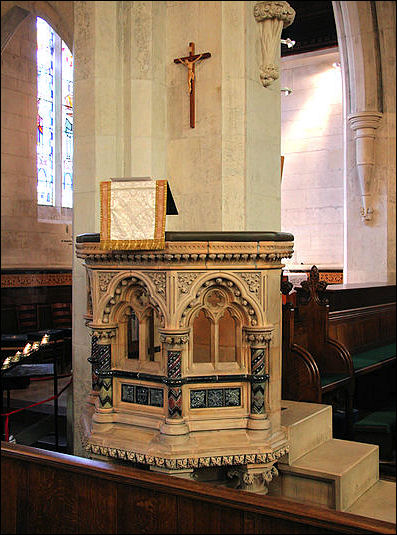

In 1887, Doulton produced one of their finest pieces of work. Alexandra, Princess of Wales led the construction of the new Anglican St Alban’s Church in Copenhagen, and Doulton manufactured and donated an altarpiece, a pulpit, and a font, of terracotta with glazed details to a design by one of his artists, George Tinworth.

Pulpit

at St Alban’s Church, Copenhagen © Wikipedia

Doulton passed away on 18th November 1897 in London, and was laid to rest at the West Norwood Cemetery in a mausoleum appropriately constructed from bricks and red ceramic tiles manufactured at the Doulton works.

By the turn of the 20th Century, the Doulton Company was renowned for stoneware and ceramics, and their products had come to the attention of the Royal Family, and in 1901, King Edward VII sold the Royal Warrant to the Nile Street Works, allowing the company to adopt new markings, and a new name – Royal Doulton. The company continued to grow during the first half of the 20th Century, producing cutting edge high-quality bone china.

Following the introduction of the Clean Air Act, the company closed the Lambeth factory, and all work was then carried out in the Potteries. Minton and Royal Albert joined Royal Doulton in 1968 and 1971 respectively.

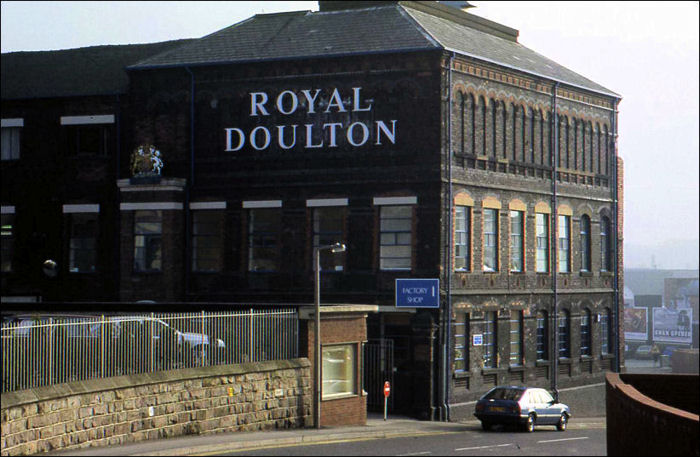

Nile

Street Works, 1980's

photo: Ewart Morris

|

Royal Doulton

plate

|

Flambé Sung Vase

|

Aerial

view of the works prior to demolition works in 2008

© Bing Maps

Royal Doulton eventually ceased production at the Nile Street Works on 30th September 2005, with production moved to a new state-of-the-art facility in Indonesia (though some of Royal Doulton’s finer products are made at the Wedgwood site in Barlaston).

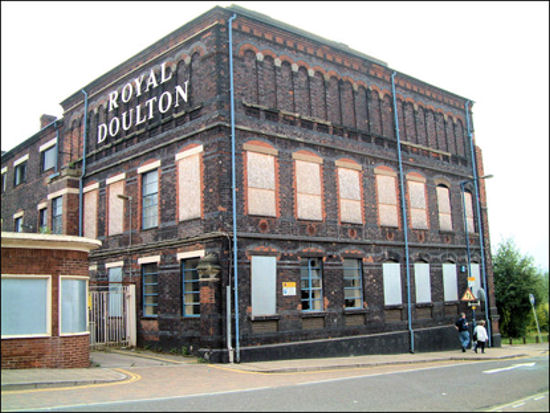

St Modwen went on to acquire the site, and aside from demolition works in 2008, and vandals stripping the remaining buildings of tiles, lead, and whatever else they can get away with, the site has remained silent, despite their talk of new homes and an ‘enterprise centre’.

When questioned about the site in May 2011, Mike Herbert of St Modwen said that the site was stalled “due to the difficult economic period”. This despite the fact that they have had their hands on the works for the best part of a decade, and acquired it at the peak of the market.

**

The Nile Street Works is one of the most important sites in the Potteries, and Royal Doulton is one of the city’s most famous brands. The brand is now part of WWRD Holdings Ltd (Wedgwood, Waterford Crystal, Royal Doulton) who are based at Wedgwood’s factory in Barlaston, and its products include dinnerware, giftware, cookware, porcelain, glassware, collectables, jewellery, linens, curtains, and lighting.

At its peak, Royal Doulton employed thousands of people at the Nile Street Works, and alongside the many other former potworks, played a massive role in Burslem’s economy. Huge numbers of workers used to flood the streets of the Mother Town during lunch hours and following day shifts, spending money and supporting the many small local businesses that populated the town.

It is no coincidence that as the presence of the pottery industry in Burslem has declined, so has the town’s economy and small business base, leaving many vacant buildings and a deteriorating built environment.

I had family that worked for Royal Doulton at the Nile Street Works: my uncle was employed there in the early 1980s, and I can recall collecting him from work with my father (who also went on to work there in the late 1980s and the 1990s), and being amazed by the numbers of people swarming out of the gates and onto Nile Street.

http://www.thepotteries.org/potworks_wk/2011/doulton/doulton_1900.jpg

Home

Time: postcard of the works c1900

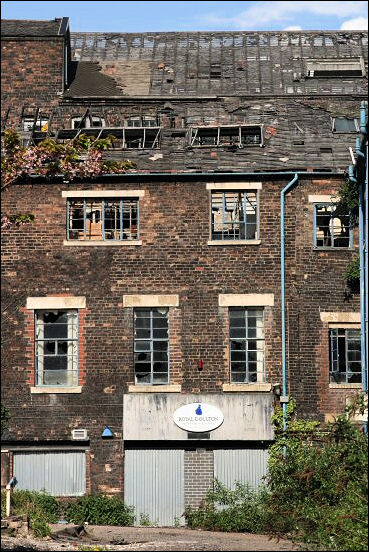

Nile Street today is completely different, and the Nile Street Works resembles a scene from the Blitz. The site is strewn with bricks and rubble, and those buildings that remain (‘protected’ by their Conservation Area status) stand isolated.

Silent. Holes in roofs, missing tiles. Boarded up windows. Vandals continue to strip the buildings of anything left of value despite the site being “patrolled” by hired security services. It is almost as if St Modwen are just willing the buildings’ inevitable collapse.

Left in

Silence

© the Sentinel

Redundant

© the Sentinel

Nile Street Blues

Appetite for

Destruction

© beautifulengland.net

Peace

© beautifulengland.net

|

And so what next for the Nile Street Works? The protected buildings continue to decline, and despite Cameron’s triumphalism over the recent economic results, the slaughter of the planning system, and the Tories’ plans to slash standards and regulations, St Modwen are as silent on the future of the site as the site itself.

St Modwen have continually used a weak economy as an excuse for their inertia at the Nile Street Works, and railed against the Conservation Area designation that protects part of the site. Renowned renovation specialists Urban Splash have applied to demolish the Grade II Listed Ancoats Dispensary recently; St Modwen are not classic restoration experts, therefore is this a course of action they may look to take on Nile Street?

And if Cameron’s crowing on the economy and his pledge of more “good news” turns out to be accurate, what will be holding St Modwen back? Or will we have further excuses rolled out?

A statue of Sir Henry Doulton stands proud on Market Place, surveying life in the Mother Town. If he could see the state of his former works right now, I’m sure he would get down on his knees and weep.

Dave Proudlove

November 2012

|

![]() back to Another 'Grand Tour' index

back to Another 'Grand Tour' index![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()