![]()

|

|

|

|

|

Stoke-on-Trent - photo of the week |

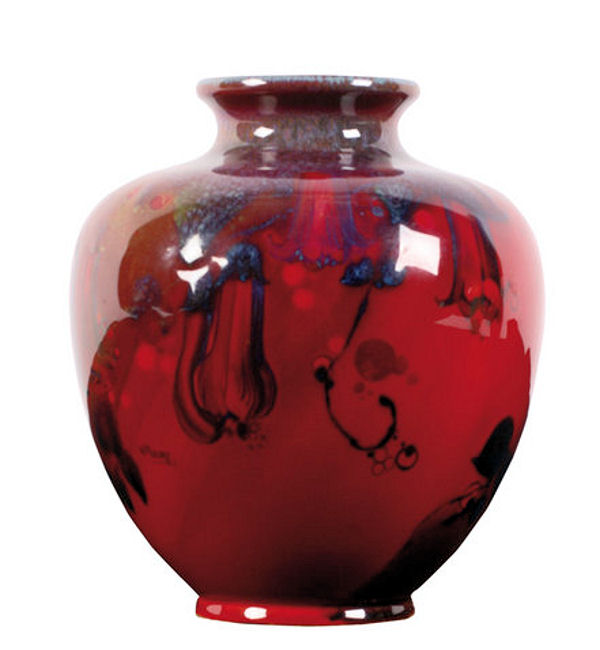

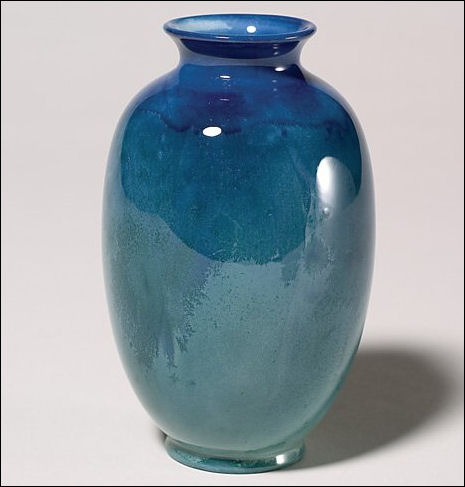

Royal Doulton Flambé

Sung Vase

Painted with datura flowers by Fred Moore.

PaintedSung mark to the base and with painted Noke signature and FM monogram

| From - "The Doulton

Story"

In 1815, John Doulton invested his life savings of £100 in a small riverside pottery in Lambeth, South London. This pottery, one of many in the area, produced a range of utilitarian salt-glazed stoneware. Aided by Doulton's three years' experience as a thrower at the Fulham Pottery, and his hard work, the pottery thrived and he became a partner.

As an intelligent and ambitious Victorian entrepreneur, Henry was probably without equal. It did not take him long to appreciate the likely impact of the sanitary revolution that was about to hit London and the new industrial cities. The Lambeth Pottery, as Doulton & Watts was now called, began therefore to turn its attention to the large-scale production of stoneware drainpipes, conduits and related wares. This development was well timed, and Doulton products were soon disappearing in vast quantities beneath the streets of London and other cities. That many of these sewer and water pipes are still in use today is a fitting tribute to the quality of the Doulton product. The Lambeth Pottery, and the Doulton family, benefited greatly from Henry's foresight, and it is important to remember that upon the firm foundation of these vital but unromantic objects was built Doulton's future reputation. Without the drains there would have been no Lambeth Studio, no Doulton figures, character jugs, tableware; indeed, probably no Burslem factory and no Doulton story to tell. One of the direct results of Doulton's involvement in the sanitary revolution was that the name and reputation of Doulton was spread far and wide. International Exhibition displays increased this still further and the company inevitably began to attract attention outside the ceramic industry. One area of particular relevance was among the newly-formed art schools which were issuing annually quantities of trained designers keen to gain industrial experience. After a lengthy battle, John Sparkes, the Principal of the Lambeth School of Art, was finally able to persuade an unwilling Henry Doulton to give employment to a few of his students on an experimental basis. Limited to standard clays, glazes and kilns, and buried away in a corner of the factory, the first students produced their rather tentative efforts during the late 1860s, with design and decoration based on well-established historical styles. These early studio wares were enthusiastically received at the Paris Exhibition of 1867 and International Exhibition in London 1871. Henry Doulton, whose success was based on his flexibility and his ability to seize opportunities that offered themselves, immediately gave the Lambeth Studio his full support and encouraged it to develop in a dramatic way. By the 1880s this Studio was employing over 200 men and girls. Co-operation between art and industry on so great a scale had never been seen before in England and, indeed, has never occurred since.

However, the real significance of the Studio was not in its products but in its effect on the ceramic industry as a whole. The Lambeth experience encouraged potters, great and small, throughout Britain, to start art departments, and so ultimately brought about the rapprochement between art and industry that Henry Cole and others had dreamt about in the 1840s and 1850s.

The Lambeth Studios flourished and encouraged Henry Doulton to cast his eyes and his ambitions further afield. Having already established factories making sanitary, industrial and architectural products in Paisley, Rowley Regis, Erith, Birmingham, St Helens and Paris, Henry turned his attention towards North Staffordshire, the traditional home of the English ceramic industry. In 1877, against all the advice of colleagues, critics and rivals, he purchased a major shareholding in the old-established Nile Street Pottery of Pinder Bourne & Co. of Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent. This company, a major producer of earthenware tableware and ornaments, also shared the universal enthusiasm for art wares. Other features which recommended it to Doulton were its interests in insulators and other industrial products. This direct assault upon the well-entrenched fortress of North Staffordshire was badly received by the Stoke pottery fraternity. They closed their ranks against Henry Doulton, regarding him as a southern upstart; they also made the fundamental mistake of not taking him seriously, having decided that he would soon be fleeing back south with his tail between his legs.

With Nile Street fully under his control Henry Doulton was able to consolidate his position. New ranges and techniques were introduced and skilled painters and modellers were brought in from other factories.

In 1889 C J Noke joined the company, initially as a modeller but later as Art Director. From his fertile mind sprang the many ranges which helped to establish the Burslem factory as a world leader in both style, technology and scale of production. Decorative figures, first shown in 1893, were introduced as an ever-growing series. From about 1901 rack plates and Series Ware were introduced in a vast range of designs. From the experimental Rembrandt and Holbein wares was developed the popular Kingsware range. This led to the introduction of Character and Toby jugs in 1934. However, Noke's greatest achievement was the creation of a range of experimental transmutation glazed wares that are at best as good as anything produced at Sevres, Copenhagen, Dresden or even in the Far East. These ranges, the Flambes, Titanian, Sung, Chinese Jade, Chang and Crystalline represent one of the greatest contributions to studio pottery made by a large British manufacturer in this century. Apart from the many forms of tableware that supplied their bread and butter, Doulton also produced many examples of high-quality artist-decorated porcelain. These fine pieces by artists such as Curnock, Dewsberry or Allen were fitting rivals for anything their contemporaries at Worcester or Derby could make. In short, the policy of the Burslem factory appeared to be to produce more diversified products than any other factory, and to produce them better. For these and other ceramic achievements Henry Doulton received many honours: In 1885 he was presented with the Albert Medal by the Royal Society of Arts and in 1887 he was knighted by Queen Victoria, the first English potter ever to receive this honour. When he died in 1897 he was lamented the length and breadth of the country. He left behind an empire that he had built out of virtually nothing. Under the direction of his lieutenants, his son Lewis, J C Bailey, John Slater, Noke and others, this empire continued to flourish and expand. Diversification brought increasing interests in architectural, sanitary and industrial areas, particularly in the new electrical field. The Lambeth factory, still largely supported by sanitary production, was able to enter the 20th century with many new and stylish stoneware and earthenware products. Even the Studio was able to survive the transition into the postwar world, a period when the definition of studio pottery was being changed by potters who, turning their backs on industry, fled into the hinterlands of Britain in pursuit of some romantic primitive ideal. In fact, the Lambeth Studio continued to exist until the final closure of the Lambeth factory in 1956 and fought to the end for the belief that true studio potters could also exist in an industrial environment, the principle launched by John Sparkes in 1860s. The final closure of Lambeth, provoked by rising transport costs and by the clean air legislation, was followed by a gradual reduction of manufacture in some other areas. Doulton concentrated their activities at Burslem and in the sanitary and industrial fields. In any case, the significance of Lambeth had been slowly eclipsed by the developments in North Staffordshire which was now the centre of Doulton production. Henry Doulton's 'invasion' had succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. By a series of mergers, first with other companies and then in 1968 with Allied English Potteries Group, a new major manufacturer emerged. Doulton & Co. today is the largest manufacturer of ceramic products in the UK, with interests in glass, industrial and sanitary wares, engineering and building materials. Royal Doulton Tableware Limited, the tableware and domestic products section, with its headquarters firmly in the Potteries, includes many companies whose names tell the history of English ceramics - Minton, Derby, Ridgway, Royal Albert, Paragon, Webb Corbett. "The Doulton Story" 1979 |

Royal Doulton Sung Ware Flambe

Vase, c. 1925

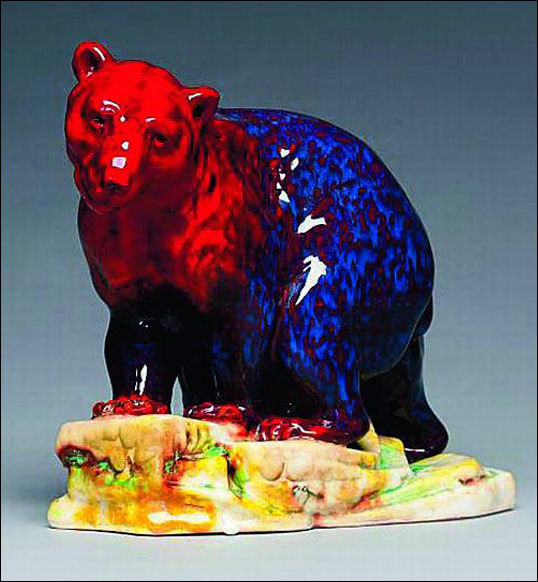

Royal Doulton Sung bear and cub

by Charles Noke,

the bear and little cub decorated in a mottled sapphire blue and red glaze, on a

cream and saffron base

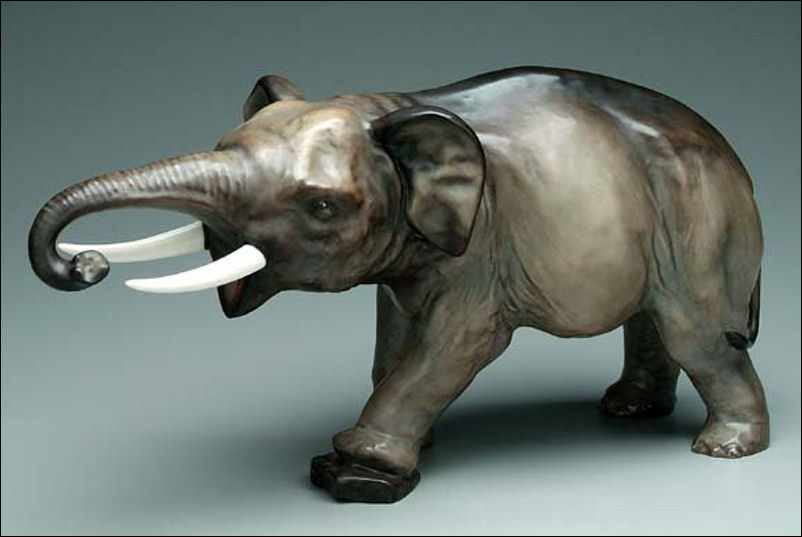

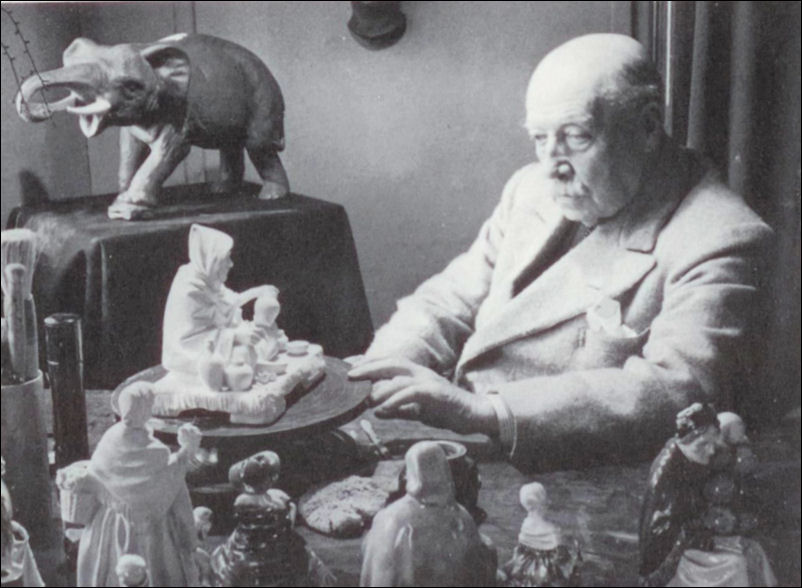

Charles Noke in his studio -

c.1930

the Elephant and Balloon Seller can be seen in this photo

The Old Balloon Seller -

produced for nearly seventy years (1919 - 1998)

and probably the most familiar of all Royal Doulton figurines

| Burslem Art Ware

When Charles J Noke was encouraged to leave Worcester and join the Burslem factory in 1889 he was able to instigate a revolution in both design and production attitudes. He became an Art Director in the broadest sense and so was able to affect all aspects of Burslem production. By his efforts a solid but unremarkable producer of earthenwares was transformed into the leading art manufacturer of the age.

The styles in use at Burslem were as mixed as the wares themselves. Many of the ornamental porcelains were freely based on 18th century French examples while the variety of naturalistic and landscape painting reflected an increasing awareness by the decorators of contemporary popular painting. By his many contributions as a chemist and glaze technician, Noke also extended the range of Burslem products. He was responsible for the unusual Rembrandt and Holbein wares with their heavy, sombre qualities. He also introduced Luscian Ware, Lactolian Ware or enamelled pottery and the delicate Titanian range. These reflected an increasing dependence at Burslem upon the modern styles of Copenhagen, Sevres and Berlin. In the early 1890s Noke began to experiment with figure models. His first ivory-glazed figures of Shake-sperean characters were shown at Chicago. From 1910 models were also commissioned from sculptors such as Phoebe Stabler, Stanley Thorogood, Charles Vyse and Albert Toft. From these beginnings developed the vast range of figures still in production.

The Burslem Studio During the late 1890s, C J Noke began to experiment with the production of high-temperature transmutation glazes, in order to recreate some of the oriental techniques of the past. These experiments were given a boost in 1900 when Cuthbert Bailey joined Doulton, as he was particularly interested in the chemistry of these exotic glaze effects.

Encouraged by this response, Doulton stepped up their 'studio' production. The flambe glazed range was increased to include animal models and other fancies, and wares with landscapes and other scenes painted beneath the glaze. From these wares developed the Sung range, introduced in 1920, which Gordon Forsyth called: 'the very finest effort yet made in the history of English pottery to produce work of high artistic value.' Flambe in one form or another has remained in production at Burslem until today. The crystalline range, another experimental high-temperature ware, was introduced at Burslem in 1907 but eventually had to be withdrawn c. 1914 as the technique, which involved the exploding of metallic crystals in the glaze, was difficult to control and therefore not viable on a commercial scale. The same problems of controlling kiln effects affected the Chinese Jade wares which were only made in limited numbers from 1920 until the 1940s. These were thick creamy glazed pieces coloured to resemble the precious stone. Chang Ware, however, took advantage of the inevitable accidents of the kiln and had a more prolific output from 1925 until the war. On this ware, several layers of thick, richly-coloured glazes were allowed to run at random and react against each other creating a varied crackled surface. Each piece was unique and the quality was far beyond conventional commercial production. "The Doulton Story" 1979 |

Royal Doulton Titanian

Vase with Crystalline glaze

|

|

|

Royal

Doulton "Chinese Jade" figure of cockatoos c1920.

Charles Noke was the pioneer of Doulton's decorative glazes in the

early 20th century

and he was particularly inspired by the monochrome glazes of early Chinese

ceramics.

The "Chinese Jade" was the most difficult of his creations, attempting

to

mimic the colour of the stone.

It proved too difficult to manufacture and so had a very limited production run.

|

related pages Processors, producers and users of potters colours and glazes

external links.. Royal Doulton Figurines - Wikipedia entry also see.. Advert of the Week |