|

The fading village of

Goldenhill

There is a jackdaw sitting on my shoulder. It has shiny black feathers and a flat head with piercing eyes that stare you down. Mrs. Joanna Price enlightens me as she welcomes me into her caravan. “Look at that crow!” I cry with some alarm. “’tis a Jackdaw that one.” She chides me for my ornithological ignorance. “There’s three others next door, and one on the van after that.”

At this point, as if confirmation was required, my eyes are diverted to another of these birds perched on the roof of the adjacent caravan. Nearby a lucky black cat edges nearer and is about to pounce upon the unconcerned bird. But a distant shout calls time on its manoeuvring and the reprimanded feline sulks away. Here it seems every living thing is being watched by every other living thing. The stalked are being stalked.

I’m spending a couple of hours with the Price family at their caravan park in Line Houses a quarter of a mile out of Goldenhill. The Prices have lived here for forty-three years since they’d been granted the land by the local authority.

The 1960 Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act brought about the closure of many private sites and shifted the emphasis to voluntary provision by local authorities. But wherever the Price family settled the council moved them on. Nomadic by nature they were kept on the move until the implementation of the 1968 Caravan Sites Act which placed a duty on councils to provide official sites. Even then it took three years to decide which land the unwelcome gypsies could occupy when in 1970, Line Houses, an abandoned hamlet, was found for them.

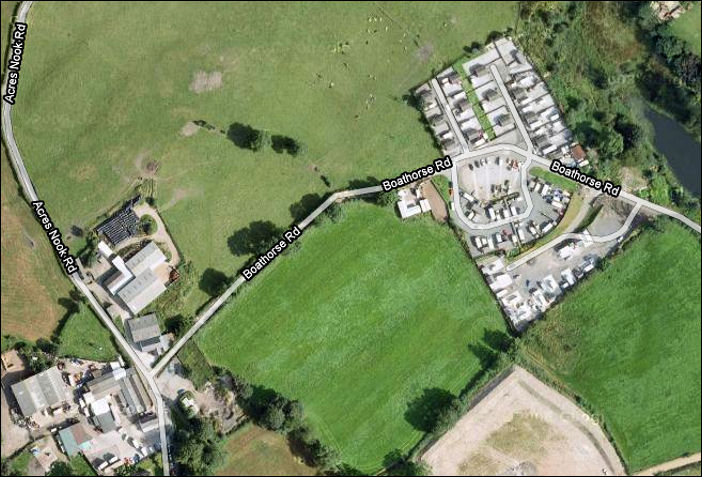

Caravan site at Line

Houses, Boathorse Road

- Google Maps 2010 -

The landscape here really is striking. Atop the Harecastle Ridge the fields roll over Audley lands of medieval incidence to Cheshire and the Welsh Marches. The lane outside the camp is Boat Horse Lane, a narrow path once used by canal boatmen who’d walk with their horses across the hilltops and down into Kidsgrove while their ware-laden barges were progressed through the long legging-tunnel by young lads along the waterway that Brindley and Wedgwood cut.

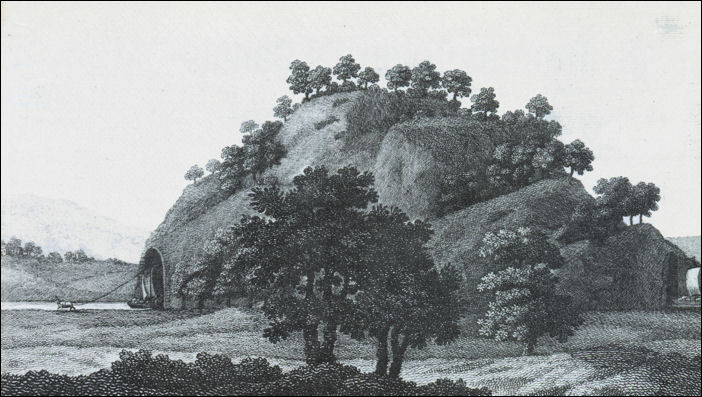

A fanciful contemporary

print of the tunnel - (1785)

a highly stylised sketch - note that the barges are shown with sails!!

and are pulled through with horses - in reality the tunnels were small and

had no room for a towpath, the barges were legged through and the

horses took Boathorse Road over the hill.

At its lowest level Boat Horse Lane yields to Church Lane, a winding hawthorn-lined track that climbs up to Goldenhill village.

At the head of Church Lane is the parish church of St John built in the Norman style in 1840 in the Liberty of Oldcott to the service of a growing community that was turning from farming to industry. So rural were the aspects then that the village of Goldenhill didn’t become recognised until boundary changes were effected in the 1880’s. Like Line Houses it was a village that grew from an encampment and was transferred for a short time in 1904 to the council of Kidsgrove for civil purposes.

In its heyday though, it was a small town with long stretches of shops paraded along its narrow high street. There were drapers and chemists, tobacconists and plumbers, newsagents and grocers and fish and chip shops. Here were a midwife and an undertaker trading side by side. In Red Lion Square there were tram sheds and a bus depot, in fact there were three bus depots in Goldenhill – PMT, Stoniors and Jeffries – imagine a village with three bus companies?

Below St John’s church was a bakery which in later years became TICO Bakery famed throughout North Staffordshire for its pasties.

St. John the Evangelist,

Goldenhill

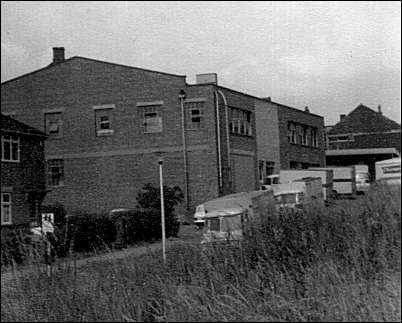

The Tiko bakery in

Elgood Lane, Goldenhill

photo: 1967

At the church I meet caretaker Tony Downes. He’s been with the congregation for 53 years and knows more than anyone about his church and its patrons past and present. He tells me the church’s foundation stone was laid by Sarah Smith Child who received Anglican baptism by Cardinal John Newman before his canonisation by Pope Leo XIII.

He mentions the Gilbert family, head teachers and leaders of the flock, Harry Gilbert junior who drowned in the sea at Blackpool at the age of 31. As Tony reflects wistfully on the past I ask him what size the congregation is today. He moves his head owlishly: “Not very many. I should say on a good Sunday about thirty but only for a morning service.” Days of glory gone I muse.

There aren’t as many people now in Goldenhill and the community character has wilted. About twenty years ago the council made its last demolition visit and removed the heart of the old terraces and shops.

According to Terry they’d promised to build a new shopping precinct and housing development in place of the central back-to-backs but instead they sanctioned the erection of a residential estate for the elderly. Terry and others are still waiting for the council’s promised regeneration programme but they have resigned themselves that it will never happened.

Across the road at Goldenhill’s community centre I meet caretaker and lifelong resident Alma Morris. She remembers a thriving village and recalls posh shops in the vein of women’s fashion couturiers Lane’s and Phyllis Salmon. In the sixties and seventies these were outstanding boutiques rated as high as any in Stoke on Trent.

Like Terry, Alma remembers the community as friendly and supportive. “Everyone knew everyone else and helped each other along.” But she believes that Goldenhill, like all industrial towns, has been compelled to change. Gone are the pits and the iron works on which the village thrived. Today Goldenhill is little more than a collection of residential homes for the elderly – there are three in High Street including Heathside House, the complex owned by the city council.

Alma also recollects the promised regeneration programme. “It’s well over twenty years ago now. They bought my house under a compulsory purchase order. I didn’t want to move but I didn’t mind because we’d been promised a new shopping precinct with underground walkways. Plans went up and everything. Then it just stopped. Nothing happened. There are no shops.”

And children have nothing to do locally. Both Alma and Tony believe the generation gap is unbridgeable. “We have to cope with vandalism and even gang fights between Tunstall and Kidsgrove youths – only why they choose to come to Goldenhill to do it I really don’t know,” complains Tony.

In their younger times neither had reason to leave the village – everything they needed was to hand. “Children were more respectful and we all took pride in our village,” stresses Alma. “It’s not like that these days. Of course then we had our own police station and a village bobby.”

But surely the community hall is successful?

“We open on a regular basis – Tuesday morning and in the evenings on the rest. Friday night is bingo night which is usually well supported but not during dark winter nights. The third Saturday each month is dance night.”

A notice in the reception area reminds regulars of a concert that is being performed by ‘The Hill Singers,’ an annual show that is very popular.

Tony rarely leaves his village but Alma says she loves going to Hanley twice each week on the bus. “I love the shops, the bright lights. Marks and Spencer’s and the shopping centre are wonderful. It’s the city centre isn’t it? I love it.”

Has she ever been to the other towns? “I went to Stoke once. I’ve never been to Longton. I wouldn’t like it there, it’s too far away.”

Tony hasn’t been to Longton either.

“I’ve got all I want here,” he says, his outstretched arms encompassing his village.

The former ‘Johnson’s Super Cinema’ is now the local Late Shop and still a focal point in Goldenhill. As youngsters Tony and Alma remember sixpenny seats under the screen with aching necks watching their flickering heroes and idols. Here was a village central to miles of open fields and farms that have now become a sprawl of housing estates.

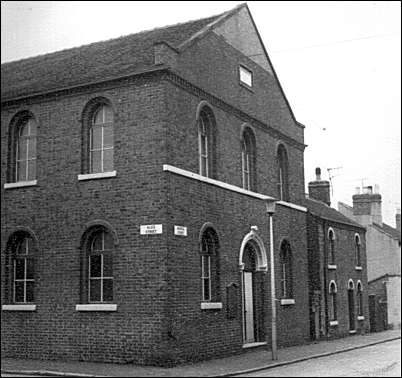

Methodist Church in

Alice Street (to left) and fronting on Andrew Street

- demolished in

1967 -

I mention the Gypsies to Alma. She remembers that the very first was Mary Toogood who had a caravan on land at the side of the Red Lion. “She was a smashing person but the council kept moving her on and wouldn’t let her settle.”

Back at Line Houses Mrs. Price recalls, “I’ve been here from the very beginning. Many has come and gone and some of us has settled in houses up the hill.”

She remembers sourly the controversial acquisition of the site and how her brothers fought the council for ownership.

“It was a lovely place and it became our home. But times are changing. The boys are moving on – and the young ‘uns watch the tele now. Times are changing fast. This is our home, we are happy here and contented and we are a part of Stoke on Trent.”

There’s a quiet harmony in Goldenhill but for how long? The village identity continues to fade and only a week or so ago the gypsies were told that they were being moved yet again and they don’t know where they are being moved to. It seems the council wants the land back to develop a new industrial estate and at the moment the gypsies stand in limbo. Along Boat Horse Lane work is already underway providing sewers for the new units and the travelling families are worried. They don’t want to move but maybe soon they will have to.

Up in the village people are moving on too. Alma prepares the community centre for a private wedding and Tony tidies around the altar for the Sunday service. A few terraced streets remain interspersed with the old folk’s homes. It’s quiet on the High Street and a First Bus stops briefly to pick up a cluster of shoppers bound for the City Centre.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()