|

I have told the story of these riots

as I saw them in part, and in part as I heard of them and have read of them.

The history may be imperfect in some details, but I have tried to give a truthful account of the incidents I saw, and of the general feeling of the time among the people.

After these alarming events there was a distinct backwash of depression, which prevailed for some years throughout the district. There was a sullen, passive reign of distrust among the people. The Reform Bill had disappointed them. All their trade conflicts had ended in failure. Even the resounding attacks against the Corn Laws, then beginning to fill the country, excited little interest among the working classes, and so they gave little response. Betrayal and failure had made them sad and hopeless.

There was a marked difference between the Pottery working people and the miners who had invaded their towns from the outside districts like a storm-flood. While having sympathy with them in their sufferings and wrongs, they were mutely appalled by their violence. The Pottery people have not the grit which makes revolutions, nor successful riots, nor even masterful trade combinations.

Visitors from the northern counties of

England, where labour organisations have been so pronounced and effective, have always spoken of the working classes of the Potteries as being too obsequious in their bearing and wanting in self-assertion. I know what this means, but I know what is called obsequiousness covers qualities which are becoming too rare in the atmosphere of democratic arrogance. I have seen other working populations, and lived among them for many years, but have never met with the same moral aroma in the relations between different classes. I have seen more strength, more dominance and more aggressiveness in the working classes in other parts of England, but not an indefinable something which seemed to lean towards the old feudal tie, but which, whatever its origin, carries a charm. Perhaps the concentration of the Pottery towns, and their long seclusion from the aggressive forces of modern industry and progress, may account in some way for the long retention of the quality I have spoken of.

The Manchester Guardian, in reviewing a book lately published, The Staffordshire Potter, says,

"The wonder is how a body of workers of singular skill, holding a virtual monopoly of a great trade, in what is virtually a single town, should have failed so signally to do for themselves what artisans under more exacting conditions have generally managed to achieve. The stamp of futility is set on everything these unfortunate potters touch."

These are strong and vivid words, nor am I surprised at the contrast between " these unfortunate potters and other artisans." These latter, all through their industrial history, have been achieving while the " unfortunate potters" have always been failing in a more or less marked degree.

There must be some special reason

for so signal a contrast. These potters are Englishmen, and are as keenly alive to their great heritage, as such, as any of their countrymen. The causes of difference must be mainly local, and acting persistently upon a population untouched by the flowing currents of movements in the larger centres of English life.

These causes, it seems to me, are various in their character and operate mainly "in what is virtually a single

town." I think I can describe some of these causes as I saw them in operation fifty to sixty years ago. I did not understand then how they were giving "the stamp of futility," then seen only by a few, but in later years seen by many.

I write now, after many years of observation of the working classes in Lancashire and Yorkshire, and where I have seen suggestive contrasts in modes of labour and in asserting the claims of labour.

I believe one of the causes of the potters' "futility" has been the want of discipline in his daily work.

Machinery means discipline in industrial operations. In the Potteries there was no such discipline, and very little of any other. I write of what I saw, and of conditions under which I and others worked. Owing, as I believe, to the absence of machinery, there was no effective economical management of a pot-works. Economical occupation of the premises was hardly ever thought of. "Cost of production," as determined by all the elements of production, was as remote as political economy in Saturn. There was only the loosest daily or weekly supervision of the workpeople, in their separate "shops," and working by "piece-work," they could work or play very much as they pleased. The weekly production of each worker was not scanned as it was in a cotton mill.

Hundreds of workpeople never did a day's work for the first two days of the week, and laxity abounded. Drinking or pure idleness were seen and winked at by the bailees and employers. It was never considered that if a week's work had to be done in four days it must be scamped to a great extent. If a man worked for these four days until ten o'clock at night, or began at four or five o'clock in the morning, this did not concern the "master," for each man found his own candle. There was loss, of course, in the use of coal for these extra hours, but this disturbed no sense of economy, for it did not exist. A man might begin to do his work on Wednesday morning, half asleep or half drunk, after two or three days' debauch, and "the bailee" might never notice him, or, if he did, he would throw out some contemptuous sneer, or some menacing words which meant nothing.

There was in all the places I knew even a premium put upon the early idleness of the week. If a man had only done about four days' work by the end of the week he might have "an old horse," that is, he would be credited with a certain amount of work which had to be done the following week. This was a sort of pawnshop method of doing business, and it was done at one of the largest pot-works in the town of Burslem. So far as I know, too, it was done more or less in every Pottery town.

Nothing can more strongly mark the absence of every economical element than such a condition, and the consequent demoralisation of the workers in the matter of production.

Now, if there had been a governing power like machinery, and if a steam-engine had started every Monday morning at six o'clock, the workers would have been disciplined to the habit of regular and continuous industry, and employers would have seen that this was necessary to economise the power of the steam-engine and the machinery.

The first scare of machinery came in my early years, and it scared not only the workpeople but the masters themselves. "Futility" breathed upon them as well as on their operatives, and after a while even some of the largest employers fled from the introduction of machinery as from a ghost.

In Lancashire and Yorkshire the same thing produced a determined struggle, but the struggle developed a fibre in both employer and workman which has been worth all it cost. It nurtured an independence whose face has scared futility from almost every province of their lives.

Further, many of the pot-works sixty years ago were rambling, ramshackle conglomerations of buildings, as if a stampede of old cottages had been arrested in their march.

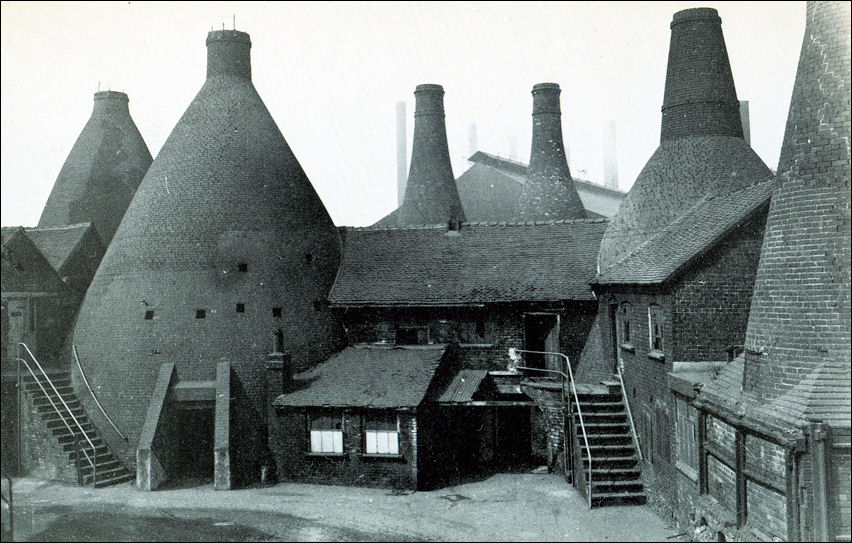

Some of the "banks" had very few square yards of open spaces. There were tortuous ways round "hovels"

and under archways, and in some even "purgatories," so-called, so that many of the workshops were separated one from one another as if, virtually, they were miles apart.

This condition hindered any common rivalry in production, and led to many forms of dissipation and idleness which could never have occurred with larger intercourse.

It also prevented any effective inspection by the bailee of the habits of the workpeople in each shop. Many of these shops were on the ground floor, and the floors were often thick with wasted clay, of which little, if any, notice was taken. The shops on a second storey were equally available for methods of killing time without any fixed purpose to waste it.

Original Bottle

Kiln Ovens, Wedgwoods, Etruria c.1952

photo: the Warrillow Collection

"Some of the " banks " had very few square yards of open spaces.

There were tortuous ways round "hovels" and under archways"

I remember in one of such shops in which I worked there were two hollow-ware pressers, one was a Methodist local preacher and the other was "a burgess" from Newcastle-under-Lyme. There was a cup-maker who was a Methodist class leader, and a saucer-maker who wanted to be one, and myself, as a "muffin-maker."

These men were engaged in discussions all the day long. In the former part of the week these would turn on the sermons preached at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on the previous Sunday. One of the hollow-ware pressers, the cup-maker and the saucer-maker attended the same chapel, but they rarely, if ever, agreed about the sermons preached or the man who had preached them.

They would dispute about questions of delivery, and whether the preachers had been simple and sound in doctrine.

Ordinarily these discussions, though earnest and absorbing, would pass pleasantly enough. Sometimes, however, their temper and tone would not have suited a class meeting, and I have seen these men leave their work benches to demonstrate in the middle of the shop floor, and sometimes lift their fists, not to fight (as a casual observer would have thought), but to give effect to their views. Usually, when this state of things arrived, "the burgess" from Newcastle-under-Lyne, who was both the "Punch" and the "wicked man" of the shop, would begin laughing or singing some political ditty, or would jump up and begin talking, as if to another "burgess" in an election dispute, and would stamp and mouth until the other three disputants would smile themselves into an abashed silence.

This burgess was not a religious man, never went to chapel or church, except to attend a funeral at the latter.

He always boasted that he voted, red or blue, for the man who gave him most sovereigns. He was fond of tobacco, and being a "hail fellow well met," he was often applied to for "a bit o' 'bacca." But his generosity was drawn upon too often, and to meet the emergency he kept an empty "bacca box" on his bench, and if anyone came to beg or borrow, he would say, "Ay, lad," and open this empty box. Then he would exclaim in well-affected surprise, "Bless me, I havena a bit i' th' world." He had christened this empty box "the world," and by this device saved his "bacca" and his reputation.

Yet this man was always the one to bring angry disputes to a ludicrous but quiet close in that shop.

I give this as a typical interior view of the waste of time in the ordinary life of one of these workshops. If the bailee or "the master" came, there was immediate silence, at a given signal. "The master" of this particular bank seemed to have no purpose in marching through a few of his workshops except to air his dignity by holding his hands under his swallow-tail coat and look loftily all round at nothing, and he generally saw it. I have referred before to waste of time by drinking and feasting in shops.

Sometimes, however, there was fighting. In another workshop I once saw a fight between two boys under ten years of age, poor half-starved lads who had no quarrel of their own, but were "egged on" by some half-drunken men in the shop to fight.

There were two other shops opening into this one, in which worked three or four "turners" and one "thrower." Altogether some twelve to fifteen people, men and women, were observers of this fight, and so had left their work. The women were all averse to what was going on, but were rudely rebuffed for their protests. The fight went on for fifty minutes. Boxing at that time was in great favour in the Potteries, for there were several well-known prize fighters in the district. These two lads fought according to the usual rules, in set rounds, and only by fists.

In Lancashire such a fight would have been over in ten minutes, as both clogs and fists would have been used. These boys got a rest after each round, and so were able to keep on for so long a time. Noses bled, and eyes began to grow black ; the fighters, too, lost all their flush, and got pale and weary. At last a big Yorkshire woman who worked in one of the shops, and who had married a potter, rushed to the lads and separated them, and stood in front of the men and defied them. She was a tall woman with a large head and face, and great brawny arms, which had not yet paled by Pottery workshops. Her eyes flashed, her brow was clouded, and her arms were held out as if for business if required. The men slunk away in their coward shame, and the other women in the shops came to her side and cheered her. The women took the lads and washed their faces, and then warmly kissed them.

I don't describe this scene for its moral

bearing, but to show how impossible economy was in a trade so loosely conducted. It would have been better for employers and workpeople if they had been in the disciplinary grip of machinery.

I have noticed, too, that machinery seems to lead to habits of calculation. The Pottery workers were woefully deficient in this matter; they lived like children, without any calculating forecast of their work or its result. In some of the more northern counties this habit of calculation has made them keenly shrewd in many conspicuous ways.

Their great co-operative societies would never have risen to such immense and fruitful development but for the calculating induced by the use of machinery. A machine worked so many hours in the week would produce so much length of yarn or cloth. Minutes were felt to be factors in these results, whereas in the Potteries hours, or even days at times, were hardly felt to be such factors.

There were alwavs the

mornings and nights of the last days of the week, and these were always trusted to make up the loss of the week's early neglect.

Their trades-unionism always presented a marked contrast to that of Lancashire. Though the latter, fifty years ago, had not the masterly organisation seen in the present day, yet it was on the lines of the present development. It had elements within it of calculation and shrewd foresight. But the trades-unionism of the Potteries was haphazard, feebly and timidly followed. It was surrounded by suspicion, for even many of those whose interests demanded its protection looked at it with misgiving and spoke of it with bated breath.

Somehow this form of self-defence and protection was regarded as tainted with the idea of moral perversion or political disaffection. I can remember men who were spoken of as trades-unionists in the same spirit and tone as others were spoken of as "poachers." This was one of the most blighting influences which fell upon all attempts at trades-union organisation.

Moreover, I know in

Tunstall, many working men were Methodists, even among the poorest, and most long-suffering. The same condition prevailed, too, more or less, in other towns. Now Methodism in those days always frowned upon trades unionism as much as on "poaching." Even a working man, though suffering himself from palpable injustice, if he were a class leader or local preacher, would warn his fellows against the "wiles of the devil." These "wiles" were often supposed to be found in trades unionism, but never in the tyranny and injustice of the "masters."

There was, too, a leaven of religious feeling in those days in the Pottery towns, which it is difficult to realise in these days. The Sunday schools mainly fed this feeling. Though few could write, many could read, and in the Sunday schools the habit of reading the Bible was strongly fostered. Through reading, the sympathy and habit of the "man in the street," though he did not attend a place of worship, were in favour of religion.

That "man in the street" would not stand brazenly in "the public ways" as now, when church and chapel-goers were going to their places of worship. The multitudinous and maudlin cheap literature of this day has brought forth after its own kindó flaunting impudence and stolid defiance. In the days I speak of, working potters who were not Methodists were yet under an influence which made them distrustful of all associations which were condemned by religious people.

I remember The Potters Examiner (though I have never seen one for over fifty years) was steeped in the forms and methods of biblical expression. I remember letters addressed to certain "masters" in the style of "The Book of Chronicles," but there was no license and no irreverence in this form of address. To the bulk of the readers of the Examiner the rebukes were all the more weighty and scathing because of the Biblical form in which they were presented.

It will be seen how this dominant feeling militated against any successful trades-union.

There were two other elements which helped this "futility" in any combination.

One was in the relation of the workmen to each other, and further, in their relation to their employers.

There was a deep and wide division between one class of workmen on a pot-bank and another. The plate-makers, slip-makers, and some odd branches were regarded as a lower caste than hollow-ware pressers, throwers, turners and printers.

The former were the hardest worked and the worst paid. The latter class had an easier employment, were better dressed and better paid. There were black sheep among these, as can be easily imagined, but I am speaking of them as a class. In this class were found many local preachers, class leaders, and church and chapel-goers.

Even those who did not regularly attend places of worship would be seen on the Sabbath "in their Sunday best."

The poor plate-makers and their kind would be seen, if seen at all, furtively running from their wretched homes, when the beer-shops were open, in their working clothes.

Now in any attempt at

union, trade or otherwise, it was impossible to unite classes which differed so widely in sentiment and habit. Two men might work in the same shop and be friendly enough in their intercourse, but if you could have seen these two men on the Sunday, or at a holiday time, you might have taken the one to be the employer of the other. I have never met with such contrasts and separation among working men anywhere else as those seen sixty years ago among the workers on a pot bank.

Another hindering element of the success of trade unionism was the relation of the workpeople to "the master." He was always "the master," regarded with awe and fear on the bank, and meekly and deferentially passed in the street, though often not seeing those who diffused this token of conventional regard. The spirit of feudalism must have saturated the Pottery district as in no other industrial district. This perhaps was helped too by the fact that up to the time of the introduction of the railway, just over fifty years ago, the people were shut up to themselves.

I remember hearing "an invader" from Lancashire about 1842 telling in our street of a strike from which he and others were suffering. But the way in which he denounced the employers of those days shocked the simpler Pottery people. They hadn't much to give, but his violence soon closed many hearts and many doors.

This fear of "the master," this overweening deference undermined all true independence of character and proper self-regard. If these elements had not existed the workpeople would never have so long tolerated their

"annual hiring," their "allowance of twopence or threepence or fourpence in the shilling," "good from oven," and the "truck system." These were carried out in abusive forms and measures, such as no other industrial population in the country would have tolerated for so many years. I saw then their demoralising and cruel results.

I saw the sufferings

of the Lancashire working-people during the American War. I saw both food and clothing rejected which would have been eagerly accepted in the Potteries between 1840 and 1850. I was on more than one relief committee, where the committees were harangued by the men because the food was not up to the quality desired, and I have seen women refuse new linsey petticoats and demand flannel ones. On such occasions my memory always went back to Tunstall market-place and the rubbish I had seen given out there.

"Futility!"

Yes, any true inner history of the Pottery working-people will account for the absence of a beneficent co-operative movement and an effective trades-union. There was a want of economical discipline in their work and life.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()