|

This was the greatest and brightest holiday of the year. For the children it was

"the maddest, merriest time of all the glad new year." There were no trip trains in those days. The full sociality of the people, undivided, was given to its enjoyment.

On the Monday the market-place was thronged. Shows, flying boats, hobby-horses, board and canvas theatres, with "the finest company in the world," "Aunt Sally," gingerbread stalls and other things ministered in their different ways to the great festival.

On Tuesday there were the Sunday school "outs" to

Trentham. "Treats" had not then come in. These have been born of the later socialistic sympathy abroad. They were much more needed then than now, for "fares" were a serious business for mothers, low as they were.

These "outs" to Trentham meant a ride there and back in a canal boat, for which fourpence had to be paid. The boat usually started about five o'clock in the morning, and it took four or five hours to make the journey to Trentham from Tunstall.

Hundreds of bundles were to be seen on that morning, these bundles containing bread and butter, perhaps a small meat pie and a currant bun or two. In some cases, perhaps, there was a small parcel of tea and sugar, but this only for those who could afford to pay for "hot water" at a cottage.

The largest number drank all they needed at a fountain near the park entrance, or at the well in the wood. I have rarely missed drinking from that well for the last fifty years, and the water comes to my lips with the same freshness "as when I was a boy."

This port of Stoke was just as attractive then as now.

Its squalor and jumble, however, were little heeded by the waiters in the boats.

The journey in the boat was a pleasant tumult from beginning to end. There was little to be seen that was new until we passed Stoke. We used to stay at this "port" an unconscionably long time. It, more than another place, should have been christened Long-port. The delay was occasioned by the locks there, and the boats waiting to get through them.

This port of Stoke was just as attractive then as now. Its squalor and jumble, however, were little heeded by the waiters in the boats. The grand sensation was to be enclosed within two narrow, slimy stone walls, and to sink or rise as the case might be.

On the first journey a youngster was filled with wondering fear at this new experience, and was only saved from a feeling of terror by the gaiety and boisterousness of his "veteran" companions who had been once or twice before.

When the top of the lock was reached, after the inrush of water, or the level of the canal gained after the outrush of water, there was a ringing shout or clapping of hands. Some of the bigger boys would indulge in rolling the boat by rushing from side to side; and some of the mothers would declare if they didn't stop they should be sea-sick. In these and other ways the journey rarely seemed a long one to most of those present.

The cottages so bright and trim on the

way

When the port was gained at Trentham there was a general hurry-scurry to get on the high road, to look on the astonishing greenery of field and wood, and to breathe the inspiring air, so fresh compared with what had been left behind, where hovels and furnaces abounded. The march to the park was a merry

revel - fun and song and laughter making the "welkin ring." The cottages so bright and trim on the way, with such clean, sweet flowers, called forth repeated outbursts of admiration and wonder. The cottagers, old and young, looked with wonder too on the pale faces, now so merry and gleeful.

As there was then no Factory Act, this was the day of sunshine and fresh air for those youngsters. Since then, what with trips

and - well, say more confidence, those cottagers or their successors don't look with very kindly interest now upon their young visitors.

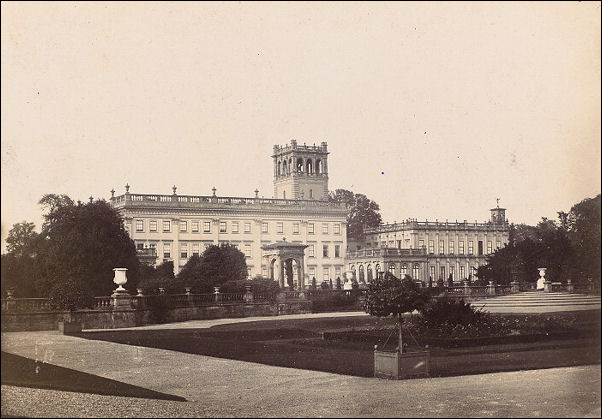

principal facade of

Trentham Hall

c.1834-1849

Trentham is visited by

thousands, and if it is necessary for this to be so that there should be a duke, may the duke live for ever, whatever may become of the House of Lords. That park has been " a thing of beauty and of joy" for many weary thousands for many years. If the dukes of the last two generations have known what simple bliss they have ministered to so many pinched lives by their generous allowance of the free use of the park, they must have had some happy moments even in spite of the heavy cares of vast wealth and property. I should not be surprised if, on "the Great Day to come," those dukes are surprised to hear the words, "Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of the least of these My brethren, ye have done it unto Me."

Rank will then be a poor remembrance compared with a rich recognition of goodness whose "sweet smell" passes even up to Heaven.

the River Trent as it

passes through Trentham Gardens

When the youngsters used to enter the

park, supposing the day was fine, there was a hurried scamper to the trees, those grand trees whose ample branches and rich foliage afforded such broad shelter from sun or shower. There the many wanderers rested. The bundles were untied, and the simple fare they contained was readily devoured in part. The different condition of things between those days and now could not be more vividly shown than by the sight of the leavings after a meal then and now. A squirrel (and there were squirrels then on the trees) could hardly have found a crumb at the bottom of the tree ; but now it seems sometimes as if as much had been thrown away as had been eaten. Prodi¬gality is not the special privilege of wealth.

After this simple feast, the park was scoured in all directions in ever-varying groups. The startled deer, rushing into the woods, gave immense delight and fun, when some unwinged juvenile Mercury vowed he would catch one. His speed and the speed of the deer excited roars of laughter by the contrast.

After a general survey of the park, you would see ringed groups assembling under the trees, especially of those who were beginning to be conscious of a soft down on the upper lip, and of the gentler sex of the same age. Perhaps it would not be going beyond the fact to say that on no green spot in England have more kissing-rings been formed than in Trentham Park. If they could all have been marked, as the rings were marked where the fairies used to dance in Robin Hood's time, they would now look more curious than the wave-undulations on some strata.

Yes, these young folks, without intending it, kissed themselves into courtship and marriage, and the link which widened and brightened out into many a domestic circle was first formed in a kissing-ring under the trees in Trentham Park. For better and for worse this was done, but let us hope that in the simplicity of those days it was mainly for the better.

The afternoon was chiefly devoted to wandering through the wood as far as " the well," and up to the monument, which was then always accessible. After tea (for those who could afford tea to the remainder of food in their bundles) there would be a slow walk back through the village to the canal boat, contrasting with the elasticity and hilarity of the morning.

'Soon the black, bitter winter would

come..' - bottle kilns in Tunstall

Most of these children

were leaving a paradise which they would not see again for a whole year. They knew it. The thought of it made some of them pensive as they pursued their way to the boat. They were going back to hard toil and to long, weary hours in stifling workshops.

They were going back to hardship, to oaths and curses and brutalities in many cases. The one glad, free, bright day was nearly gone. Except on Sundays, they would never have anything like it for a whole year. Soon the black, bitter winter would come, and through sludge and storm, and only half-clad, they would travel from home to "the bank," and from the bank home, never seeing the latter in daylight for many months, except at week-ends.

With so much that was bright and beautiful behind, and so much that was hard and chilling before, is there any wonder that some of the more thoughtful were pensive on their way to the boat ? If England's legislators could have seen these children passing out of the sweet sunshine and fresh air into the darkness and hardship of their daily lives, they would not have allowed them and their successors to continue in those toils and cruelties for twenty-five more years. "Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers," and no wisdom seems to linger so much as that of statesmanship where vested interests are in the way. But thank God time doesn't linger, and "throughout the ages one increasing purpose runs, and the thoughts of men " (and the privileges of men) "are widened by the process of the suns."

Many of those children, as they afterwards sang in their Sunday schools of "sweet fields beyond the swelling flood stand dressed in living green," would associate that bright and hopeful vision with what they had seen in Trentham Park. And the soft twilight comes on as the boat is steered on its homeward journey.

The boat is now full of jollity, for numbers spread the contagion of joy. The stars come out, as if to view with smiling, pensive interest these happy children. Trentham with its wooded heights fades in the distance, but to many in this boat its memory will be a sweet vision and an inspiring hope amid the sad and sorrowful toils of the year.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()