|

It was a battle between brains and brawn, money men and

grafters. Margaret Thatcher and the Tory Government of the time were

insistent that coal mining in this country was uneconomic and

expensive and could be imported for less, and that deregulation of

financial markets would make everyone rich.

They were wrong, on both counts. Maybe the coal industry was

uneconomic at the time, but that was a short-term view, whilst

financial freedom has simply led to polarised communities, with the

rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. On election in 1997,

Tony Blair vowed to eradicate poverty, but this has proved nigh on

impossible thanks to the untamed monster that Thatcher and her friends

created, allowing financial experts to create more ingenious ways to

make money. Maybe the pain that they are currently suffering is some

form of social justice.

Margaret Thatcher and her Government may have had valid points, and

ultimately an argument that could have been won. Deep down though,

she believed that the strike was unjustified, and it presented her

with an opportunity to flex her political muscles and hone her Iron

Lady image. And that she did.

However, what has caused most damage and hurt was the virtual

abandonment of coalfield communities that followed, communities that

were raised on coal, that relied on the industry for their living.

Told to “get on their bikes” to find new sources of employment, such

communities became alienated from mainstream life, with the now

recognised social ills of such public policy (drug and alcohol

abuse, health issues, housing problems) spiralling out of control.

Various Government-sponsored initiatives were developed to help

combat these problems, but the funds made available were mere

breadcrumbs. Former colliery sites were transformed into business

parks and new housing estates, and were trumpeted as the saviours of

coalfield communities.

However, many former colliers have not found new work on the revamped

pit sites, and very few mining families live in these new homes.

Indeed, coalfield areas continually come out at the top of lists of

the country’s most deprived communities. If there are any lessons to

be learned from regeneration programmes in such places, it is that

there must be more of a focus on the people that mined coal and their

families, rather than the sites and buildings.

Remnants of the mining industry in North Staffordshire are fast

disappearing. For example, Hem Heath colliery has been reclaimed and

is now a massive business park and the home of Stoke City Football

Club, Wolstanton Colliery is now a retail park that includes a 24

hour supermarket, and Norton Colliery is being transformed into a

huge soulless housing estate.

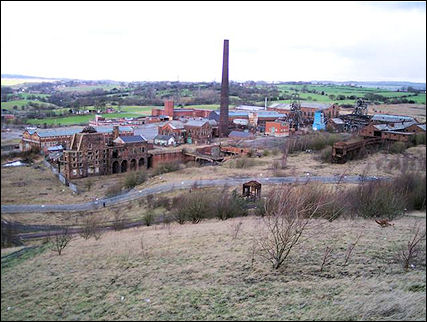

However, the Potteries possesses possibly the most complete former

colliery site in Europe in Chatterley Whitfield. Chatterley

Whitfield was one of the most productive mines in the country and

was the first colliery in Britain to achieve an annual output of

1million tons. The site is now a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

|

Chatterley Whitfield

The site lies around two miles north of Tunstall on the Potteries

coalfield, which is the largest in North Staffordshire. It is

considered that the Cistercian monks of Hulton Abbey may well have

extracted coal from Whitfield in the fourteenth century – there is

evidence to suggest that they mined coal from bell pits at nearby

Ridgway – but the first recorded workings on the site were by a

Burslem coal merchant in 1750. |

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the

site was developed as a colliery, and by the mid-1800s there was an

on-site engine house, wharf, carpenters shop, and brickworks.

In the 1850s, a prominent local businessman, Hugh Henshall Williamson,

expanded production, and after initially working ‘footrails’, he

subsequently sunk a number of shafts, including the Bellringer, the

Ten Foot, and the Engine Pit.

Further expansion of the mine followed the opening of the Biddulph

Valley Railway in 1860, and in 1865 a consortium of businessmen from

Tunstall acquired the colliery and went on to form the Whitfield

Colliery Company. In 1872, the managing director of the Chatterley

Coal and Iron Company, C. J. Homer, bought the site, and went on to

invest heavily in railway infrastructure.

However, this led to insolvency, and the company went into voluntary

liquidation in 1878. Production continued through an administrator

until 1890 when the business was acquired by a newly formed

Manchester-based company, the North of England Trustee Debenture and

Asset Corporation, who continued to own the site until the industry

was nationalised.

|

The Institute Shaft

The colliery suffered during the recession of the late 1920s and

early 1930s, but as the economy recovered in the years leading

up to the Second World War, the company invested heavily in the

new plant, workshops and railway equipment, and in 1939,

Chatterley Whitfield became the first colliery in Britain to

achieve an annual output of 1million tons of coal.

Following the Second World War, much modernisation occurred, and

in the early 1960s, ambitious plans were formulated to merge

Chatterley Whitfield with the nearby Norton and Victoria

collieries to create one ‘super colliery’ that – it was

envisaged – would have been capable of an annual production of

2million tons. However, this would have required significant

investment, and so the plan was never implemented.

Chatterley Whitfield ceased production on 25th March

1977, with the remaining seams worked from Wolstanton Colliery.

|

|

Platt Winding House and Chimney Stack

The following year, the now defunct Chatterley Whitfield Mining

Museum opened its doors to the public, with access to the

underground workings via the Winstanley Shaft, and at its peak,

attracted 40,000 visitors a year. Following the 1984-85 Miners’

Strike, the colliery at Wolstanton was closed, and this led to

fears that the Chatterley Whitfield workings would flood. As a

result, the National Coal Board invested £1million in the

construction of a simulated “underground experience” in former

railway cuttings south of the Institute Winding House.

In August 1993, the museum went into liquidation, and the site

reverted back to the City Council who owned the freehold. In

November of that year, the site was designated a Scheduled

Ancient Monument. It is also home to a host of Grade II and II*

Listed Buildings. |

|

Electrical and Mechanical Fitters Shop

The City Council have been working for a number of years to

restore the site, and bring it back into use, and in 2002, the

site was included in English Partnerships’ National Coalfields

Programme. Work on site is well underway, and an enterprise

centre has been opened, and civil engineering contractors Birse

are in the process of laying out a new country park.

Whilst the future for this former colliery seems bright, let’s

hope that the most important element of all coalfield

communities is not forgotten: the people. |

David Proudlove 13 Apr 2008 |

![]()

![]()

![]()

details on the Whitfield Listed Buildings