|

Stoke-on-Trent – the Potteries – has

always had bad press. Priestley commented that the human race had

yet to arrive here in the 1930s. Pevsner famously described the six

towns, or five towns as both he and Bennett christened the city, an

“urban tragedy”. In the swinging sixties, then Government minister

Richard Crossman felt that the place ought to be abandoned and that

any attempts at ‘urban renewal’ would be a huge waste of time and

money. In recent times, Stoke-on-Trent has been named the worst place

in the country to live. Are such views accurate, or is the place and

its unique qualities simply misunderstood?

The prevailing image of

the Potteries to those from farther a field is that of pits and

pots, and smoke and stench, in spite of the fact that the pits have

gone, the pottery industry has changed beyond all recognition, and

the city now has one of the greenest urban landscapes in the country

thanks to its Victorian parks and award-winning land reclamation

programmes. Stoke-on-Trent has always thought to have been in need

of ‘cleaning up’, and ridding the city of her smoke and grime

generating potbanks has been a part of the on going clean up. Never

mind the beauty of the potbanks’ products. Never mind the beauty of

the buildings themselves. Never mind that reuse of existing

buildings can often prove more sustainable than clearance and

redevelopment.

Gladstone Pottery Museum: the classic potworks, and one of the first to be restored

Over the past couple of decades

there has been a much greater appreciation of industrial heritage and

architecture, from the huge dockland warehouses of Liverpool and the

east end of London, to the famous Lancashire cotton mills. Great

examples of this appreciation include the reuse of the Sir Alfred

Bird’s Custard Factory in Birmingham, the resurgence of Ancoats in

Manchester, and the transformation of the Great Western Railway

Engineering Works in Swindon. The Potteries has its own abundance of

such heritage in its potbanks, yet there has not been the emphasis on

reuse and restoration as in other industrial cities. Why is this so?

The seeds of such

apathy towards the Potteries have probably been sown by the potters

themselves; in 1991, the Royal Commission on the Historical

Monuments of England published Potworks, an overview of the

city’s industrial architecture, which detailed many images and

descriptions of beautiful, long gone potbanks such as the Hill

Pottery in Burslem, and Fenton’s Foley Potteries, pulled down by

companies looking to yield value from cleared sites while moving

operations to other locations in cheaper, easier to maintain

buildings of little art or character, with such activity supported,

and in some cases encouraged, by former and current civic

dignitaries who ought to hang their heads in shame. Some of the

buildings referred to in Potworks – while around at the time

of publication – have long since gone.

I understand the

arguments of outdated facilities, and modernisation of processes,

but if the people of the Potteries cannot appreciate and respect the

city’s industrial heritage and architecture, how can we expect the

profit-hungry monsters of the development industry to do the same?

Indeed, Stoke-on-Trent as a city is undervalued in terms of its

architecture and heritage (and not just industrial architecture),

with just 192 Listed Buildings. Given the city’s size in terms of

population, and its rich industrial history, this is a great shame.

|

Dudson Centre,

Hanover Street, Hanley

There

have been some great examples of a positive approach to reuse of

potbanks though.

Hulme Upright

Manning of Festival Park have brilliantly restored the Dudson Pottery

works on Hanover Street in Hanley, including some well executed modern

interventions, to create the Dudson Centre, which houses the Dudson

Museum, conference facilities, and provides office accommodation for

local voluntary services.

This is arguably Hulme Upright Manning’s most impressive work in

years.

The courtyard and bottle kilns of the Dudson

Centre |

|

The soon to be transformed Eastwood Pottery

-photo 1999-

The much maligned housing market

renewal pathfinder, RENEW North Staffordshire, has taken a cue

from other major cities, and include in their vision to

rejuvenate the area, plans to reuse the Eastwood Pottery on

Lichfield Street, Hanley as part of the new canalside community,

City Waterside.

RENEW also plan to create much

needed space for small businesses at Atlas Works in Shelton.

However, cynics may suggest that this is a tokenistic gesture to

pacify those accusing them of ignorance of the importance of

some of the city’s housing stock. |

This is the good news.

Other potbanks may not be so lucky. Arguably the potbank with the

finest frontage is Boundary Works on the edge of Longton. Its Grade II

Listing may save it from the usual clearance approach, but unless the

local authority utilises its statutory powers in terms of forcing

repairs, this impressive building may yet disappear through

deterioration and neglect.

The historic Spode site

on Church Street in Stoke, possibly the oldest surviving largest

pottery manufactory’s in the city, and a great example of a potbank

that has grown organically as opposed to have been planned, could be

considered ‘under threat’ from major redevelopment.

Other potbanks at risk

from either ‘comprehensive regeneration’ or neglect include the former

Royal Doulton site on Nile Street, Burslem (owned by ‘regeneration

specialist’ St Modwen, not known as classic restoration experts), the

Falcon Pottery on Old Town Road, Hanley, and Portmeirion’s Falcon

Works on Sturgess Street in Stoke.

David Proudlove 12

December 2007

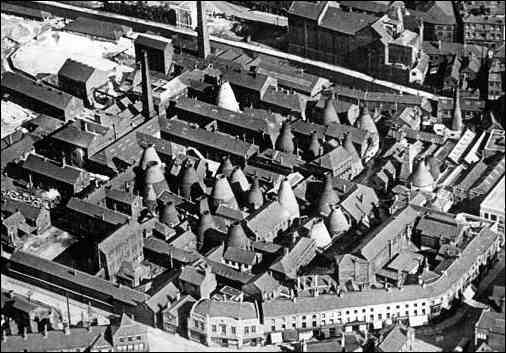

Aerial view of Spode China Works, Church Street,

Stoke, 1927

-click for larger picture-

Falcon Pottery of J H

Weatherby & Sons, Old Town Road, Hanley

-click for

more on Weatherby-

The frontage of the

Boundary Works, King Street, Longton

|

![]()

![]()

![]()