|

A traveller in 1750 walking the back lanes

through the fields from Handley Green (Hanley) to Stoke Parish Church

would have had a wholly different view. As he drew level with Shelton

Farm, the last vestiges of which would later be known as Mayer's Field

with its attendant abattoir, he would continue south down the gentle

slope of Stoke Fields along the farm track later to become Victoria (and

later still College) Road.

|

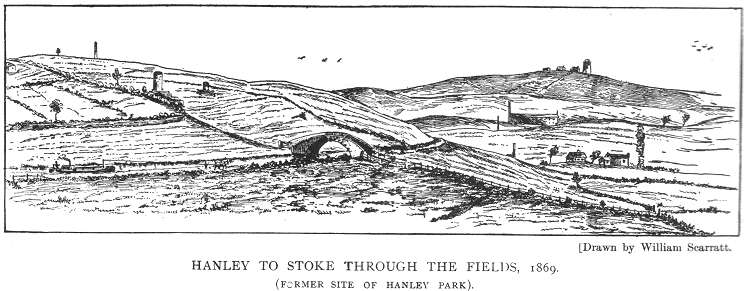

This drawing from a book written in 1906 by William Scarratt

called "Old Times in the Potteries" illustrated the area

called 'Stoke Fields' which was purchased to build Hanley

Park.

A footpath from Stoke to Hanley is running diagonally across

the picture and the path crosses the Caldon Canal over the

bridge. This area was described:

"Down Stoke

Fields were a few whitewashed huts with patches of garden.

The Victoria Road bridge existed, but for the use of the

farm only. The one to the left of the park pavilion was the

one on the Stoke Fields footpath. Shardruck, mounds and

ventilating shafts were far more plentiful than houses." |

Crossing the boundary between Shelton Farm

and entering the Parish Glebe Land of Winton's Wood, he would see

stretched out in front of him, the broad, shallow valley of the River

Trent, the course of which lay some few hundred yards to the east beyond

Leek Road at Trent Hay Farm, the smaller Fowlea (or Foulhay) Brook

running south from Linehouses to join the Trent a mile away near the old

Derby to Chester Roman Road, Rykeneld Street.

The River Trent rises some 900 feet above

sea level, under the shadow of Lask Edge on Biddulph Moor 9 miles to the

north, drops 500 feet in that distance, and then continues south,

sweeping round to the north on its slow 150 mile journey to join

the Humber near Scunthorpe, almost at sea level. The 9th Century

stone-built Parish Church of St Peter ad Vincula lay just to the north

of Rykeneld Street, with the Rector's house Stoke Hall across

the road to the south.

The dilapidated Parish Church which

had been altered and enlarged many times during its long life was

becoming ruinous and like Stoke Hall stood on a moated site as a defence

against the periodic flooding of the nearby river. The traveller would

see a few thatched cottages in the fields with here and there a

small coal pit, but the most significant man-made feature in the

landscape was the church, with the nearest hamlets at the ancient

hill-top settlement of Penkhull to the southwest, and further down the

Trent at Boothen. Our traveller could have turned onto another farm

track, which later became Cauldon Road, and then south onto yet

another rough track ( later Boughey Road ), before completing the last

half mile to the church, crossing the Fowlea Brook by means of a small

cart bridge on the way.

|

"Fowlea by name and

foul by nature"

The

Fowlea brook (2000) as it runs at the bottom of

Leason Street in Stoke.

On the left the brown building is

part of the Spode factory and in the middle the

blue building is anindustrial electrical factory

on Elenora Street.

The Fowlea Brook runs through a culvert under

Elenora Street

|

The landscape was generally flat and

undulating with a trend to the south; the land itself was not of the

best agricultural quality, being poorly drained and with deposits of

coal and clay near the surface. He would have seen higher ground to the

south and east across the river, at Fenton Low (Berryhill) and Great

Fenton (Mount Pleasant).

Horse drawn traffic:

When he left the Handley Green to Stoke

road at Shelton (Rykeneld Street), he would have been aware of the

constant horse drawn and pack horse traffic plodding in both

directions, carrying out finished pottery ware from, and bringing in

foreign clay and flint to the potteries at Burslem and elsewhere. The

nearest navigable waterway to the east was the Trent at Willington near

Burton, which having collected water from various tributaries along

the way, was at that point deep enough for substantial water-borne

transport. It was to this location that the land traffic from the

potteries was bound, for down the river lay the port of Hull and the

German Ocean, an outlet for the ware and an entry point for the imported

clay and flint, and the return road journey to the Potteries.

There should be no illusion that the

overland journey to the Trent at Willington was easy. The roads were

roughly surfaced, dusty in summer and sometimes impassable in winter.

However the journey from Burslem northwards was far worse. The direct

route through the pottery hamlets was, according to a Petition

presented to Parliament, ..so very narrow, and foundrous as to be

almost impassable for carriages, and in the winter almost so even for

pack-horses. The better, alternative route lay through the Loyal and

Ancient Borough of Newcastle under Lyme, but was double the distance and

subject to Newcastle's Tolls.

The main northerly destination for finished pottery ware, was the port

of Liverpool, from where Josiah Wedgwood had already begun an export

trade. The overland route extended as far as the River Weaver at

Winsford, where water transport was available, connecting with the River

Mersey and the port of Liverpool. Similar to the eastern route to and

from Hull, the return journey brought in clay , flint and Cheshire salt

for the glazing process.

Turnpike roads:

In 1762 a large body of potters which included Josiah Wedgwood,

petitioned Parliament for the authority to construct, widen and

operate a Turnpike road from Red Bull at Lawton, Cheshire to Cliff Bank,

Staffordshire (possibly Hartshill Bank, Stoke) where the non-Turnpike

road from Burslem, Hanley Green and Shelton joined the Newcastle to

Derby Turnpike, thus creating a continuous, better standard road from

north to south through the potteries. Josiah Wedgwood gave evidence to a

Parliamentary Committee to this effect in 1763.

The Loyal and Ancient Borough, well used to

receiving income from travellers through the town, objected strongly to

this threat to their economy. It appears that a compromise was struck

and the ensuing Act for the time being, permitted the new road

only south as far as Burslem. The historical antipathy between

Newcastle and the Potteries was apparently alive even then. However,

although the principle of improved road communication had been

established and more improvements were to follow, the far-sighted

Josiah Wedgwood in 1765 met James Brindley the canal engineer at the

Leopard Inn in Burslem and a new era began.

Population:

At this time the population of the

Potteries Townships would have been about 7,500 souls, with Hanley and

Shelton accounting for about 2,000.

next: canals

previous: the very early years - the times of the Romans and Normans

|

![]()

![]()

![]()