|

Growing population &

industry:

If we fast-forward to 1785 we would find

that despite all the difficulties, the dawning Industrial Revolution was

drawing people in from the countryside, and the population had grown to

15,000 for the area, and to 4,500 for Hanley and Shelton. Small

cottage-potteries were being superseded by new brick-built and

tile-roofed manufactories, with the consequent demand for housing, goods

and services, the brick-making industry not lagging far behind the

potteries and coal mines. Our traveller, now elderly, could be walking

the same route as in 1750, perhaps this time accompanied by his small

grandson, musing on the throngs of people who seemed to be everywhere,

and on the latest visit to the area by Mr John Wesley who had last year

preached at Handley Green, breathing fire and Dissension.

The canals:

Being a staunch member of the Established

Church, hence his frequent journeys to the Parish Church of St Peter ad

Vincula in Stoke, our Man disapproved of these new ideas, but as he

stepped along his way, he marvelled at the sight in front of him. Mr

Wedgwood's new Caldon Canal, opened about five years ago, lay in his

path. He paused on the hump-backed bridge to watch a horse-drawn barge

glide slowly but surely past, with a cargo of limestone from the

Moorlands hills away to the northeast. Wedgwood's engineer, James

Brindley had designed the canal along the brow contour of the

shallow escarpment that encircled Shelton and Handley Green, so that on

the level it required less locks. The Caldon Canal was supplied with

water from man-made lakes and conduits up in the hills. Wedgwood's major

project, the Grand Trunk Canal of which the Caldon Canal was but an

arm, had been started in 1769 and was opened in 1777, connecting the

River Trent with the River Mersey through the Harecastle Tunnel.

From this point in history the only way was

forward. Even before 1769, Wedgwood had opened his new pottery at

Etruria on the line of the new canal. Other potters as well as his

engineer James Brindley scrambled to buy land and to relocate on or

near this new marvel. The canals needed good road links, and road

building was improved at the same time thanks to the enterprise and

diligence of men like John Metcalf (Blind Jack of Knaresborough) whose

methods soon became widely used.

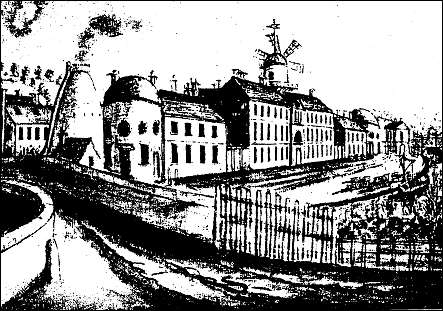

The

Wedgwood factory from the canal bridge at Etruria Road in 1794

We had left our travellers on Caldon

Canal bridge, looking down towards Stoke. Their onward journey would be

largely unchanged in this predominantly agricultural environment, but

new building especially ribbon development along the highways was

becoming noticeable. On the way to church when crossing Winton's Field

they stopped to dabble in the small man-made channel that ran from the

Trent near Trent Hay Farm, to the Grand Trunk Canal in Stoke. This feeder was the first contribution of water from the river to the

canal that would one day bear its name- the Trent and Mersey.

The line of the canal

feeder

As they crossed the Grand Trunk Canal they saw a much busier waterway

than the Caldon with wharves and loading docks in both directions; a

veritable hive of activity. Sadly James Brindley died in 1772 and did

not see the completion of his last enterprise.

Stoke Church was even more dilapidated than

ever, and Grandfather was of the private opinion that it was in danger

of falling down. The Domesday Survey had valued it at 10 shillings.

on

Domesday on

Domesday

next: railways and chartists

previous: the early years - 1750 onwards

|

![]()

![]()

![]()