|

Newcastle-under-Lyme Junction Canal

"Raising interest in

canal lift idea was a problem"

click the

"contents" button to get back to the main index & map

next: Sir Nigel Gresley's canal

previous:

Newcastle-under-Lyme

Canal Pt 3

|

Historian Fred Hughes

writes....

There’s

little doubt that the canal from Stoke to Newcastle was compromised by the

so-called Gresley monopoly. Sir Nigel Gresley’s Canal running from his

coalmines at Apedale and the Stoke Canal both terminated in Newcastle. All

that was needed was to connect them – but was there a will.

“Both

canals had been relatively easy to put together. The next move was to join

the Stoke Canal ending at Brook Lane to the Apedale Canal a mile up the

road at Cross Heath,” says Andy Perkin of the Potteries Heritage Society.

“So a connecting waterway known as the Junction Canal was cut. Although it

finished level with Brook Lane it stopped at a higher point making the

handling of haulage between the two terminals laborious. One answer was to

construct an inclined plane, a sort of rail lift, in the location of the

steep gradients of Occupation Street. But the inclined plane was never

constructed and interest waned.”

The

Junction Canal through Newcastle opened in 1799.

|

“Gresley’s

Apedale Canal ended half-way along Liverpool Road just below and opposite

where St Michael’s Road is today,” adds historian Steve Birks. “The

Junction Canal started here and curved east around the town centre through

the Brampton and into Stubbs Fields. As Andy points out, when it was up

and running the transferral of goods between the two terminals from one

level to another had to be made manually. Clearly this was never going to

be commercially viable. But too much time was spent considering

alternatives.”

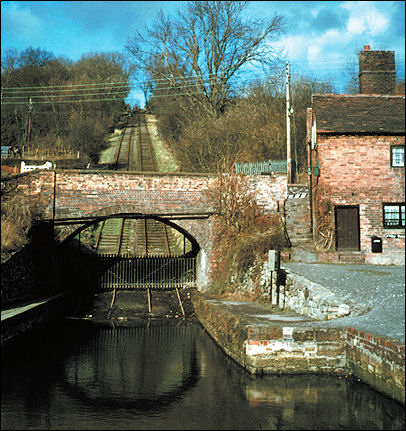

the end of Marsh Parade

and the gates to Stubbs Walks

this was the route of the Junction Canal

|

The

inclined plane had been talked about for a long time. But continued

postponement increased the cost of what was a major engineering project.

Mining historian and chairman of Newcastle Civic Society, Jim Worgan, has

studied the options faced by the shareholders.

“The

canal from Stoke to Newcastle was hampered immediately by Gresley’s

monopolising conditions on the price of coal carriage,” Jim says. “Trading

was generally poor except for the transport of coal to and from Gresley’s

own coal wharf in Liverpool Road. The other wharf, belonging to the Stoke

Canal at Stubbs Field, was hardly used at all. To remedy this, the

shareholders brought the inclined plane project back onto the agenda to

provide cost-effective means of conveyance up the hill through Occupation

Street. In 1831 the frustrated shareholders called upon the engineering

whiz kid of the day, none other than the railway genius George

Stephenson.”

The Hay Inclined plane in Shropshire

this is what the Newcastle Junction canal plane might have

looked like if completed

Stephenson was a Geordie born in 1781 to parents who were both

illiterate. As a consequence he received sparse education eventually

paying for night classes when he was 17 from his earnings at a local

colliery. After marriage he supplemented the household income by making

shoes and mending clocks. By the time the new owner of the Apedale

mines, Richard Edensor Heathcote, somewhat half-heartedly invited him to

sort out the Newcastle Junction Canal, George Stephenson had invented

Rocket, the fastest train on earth, and had established the world’s

first commercial railway between Stockton and Darlington which pioneered

rail travel as we know it today.

Jim

continues. “In 1832 Stephenson presented his designs for the construction

of an inclined plane from the basin at Brook Lane to Stubbs Fields. The

starting cost was £2,206. Despite this reasonable sum (about £1.5 million

today) the shareholders had difficulty in persuading Heathcote to lease

the Junction Canal to liberate funds to build Stephenson’s project.

Heathcote eventually turned his back on it; after all his investments were

already safe – the great iron and coal master wasn’t particularly bothered

about linking with Stoke. Beside the industrial world was opening-up to

railways and he could see superior benefits.”

In fact

by 1846 a new rail line had been laid-out from Stoke to Silverdale through

Newcastle. The Stephenson’s inclined plane on the Junction Canal was no

more than a half-remembered dream.

“Most

of the canal bed was used for rail track,” says Jim. “Of course that’s now

gone as well. But you can follow the line quite easily from Marsh Parade

and Water Street, across King Street by the Borough Arms, along a greenway

and under Queen Street into West Brampton. From here the railway travelled

through a tunnel under Liverpool Road to Knutton and Silverdale. The

Junction Canal however took a different route from West Brampton.”

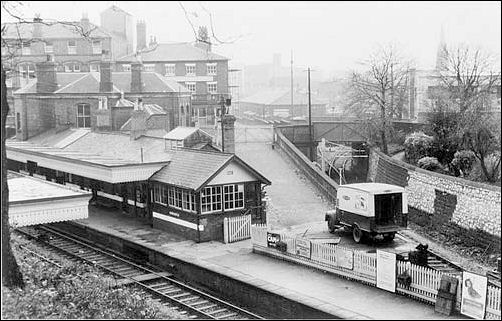

Newcastle railway station

- situated off King street

30 May 1964

Newcastle railway station was situated off King street, across from the

Borough Arms Hotel, as this photograph clearly shows.

Jim

offers to walk me along what’s left of the bed of the Junction Canal. The

start point is Hempstalls Lane.

“This

area was once occupied by the grounds of Rye Bank House,” he points out,

“An early home of the Caddick family and built alongside the railway in

1847. Nearby were the Brampton Sidings which still carry the name today.”

Jim and I

walk along a dead-straight stretch now called Croft Road, through a modern

housing estate via Honeywood and into a row called Brackenberry all of

which stand on the canal bed.

“We are now walking parallel to St Michael’s Road Cross Heath,” says Jim.

“From this point the Junction Canal passed under Liverpool Road where it

connected with the Gresley Canal near Swift House. As for the actual

connection – it’s been long buried by modern industry and transportation.”

more on the

Junction canal

more on the

Junction canal

|

![]()

![]()

![]()