“My grandfather, Charles Henry Riley, was the innkeeper of the Swan

Hotel in Burslem for many years,” says local businessman David Riley.

“He was the king of his castle at the hub of the town and everybody

conformed accordingly. Regulars were favoured while troublemakers knew

better than to ask for admittance.

The local police used his backroom each afternoon for private sessions.

The local barber called round to cut his hair and groceries were

delivered to his door. He had a parrot each end of the bar one of which

was named Joey that repeated everything it heard. ‘Is Norman in?’

customers teased. Norman was my dad. And Joey would repeat – ‘Is Norman

in?’ Sometimes rude words were repeated. But my grandfather loved that

parrot. The only time I saw my grandfather cry was when the parrot

died.”

|

“I’m not entirely certain whether this was by device or desire,” says

Tunstall historian Don Henshall. “Certainly there seems to be a large

gathering of publicans here in the old part of the cemetery.

It’s really amazing to see how many are listed – Arthur Rigby of the

Wheatsheaf, Edwin Bloor of the Dog and Pheasant. Luckily the Wheatsheaf is

still standing. But many of the others have disappeared in Tunstall’s

changing face; the Plough Inn, the Black Horse, the Prince of Wales and

the Bridge Inn. Where are they now? Where were they then?”

I rub my eyes in disbelief to find that Don is right. Eleven graves in a

row as though they’d all been lined-up for one final glorious happy hour.

“Arthur Rigby who died in 1937, was pretty special from all accounts,” Don

continues. “He was so popular the patrons had a mosaic front doorstep laid

out in memory of him. And it’s still there.”

Here lie publicans and poets; the famous and the not-so-famous; side by

side in death. |

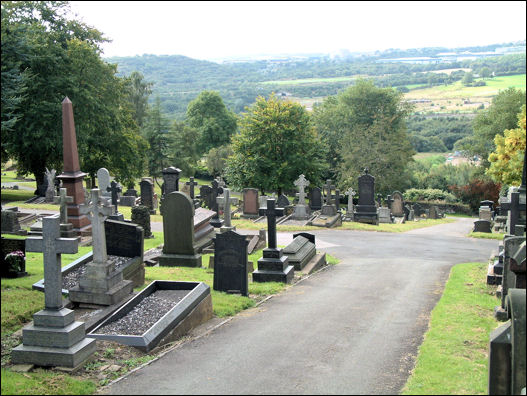

“Tunstall cemetery is really unique,” says historian Steve Birks. “It

lies on the eastern slope of Chatterley Valley and is so steep that you

wonder how the graves manage to cling to the side. I mean they’re all laid

level which means that often one end is tilted so much higher to

accommodate the sheer landfall. But this lends a lot to its charm.”

Graves clinging to the side of Chatterley Valley

Tunstall Cemetery was settled on part of an ancient piece of land known as

Tunstall Farm in 1868.

“The Sneyd family were the owners of about 1250 acres in the manor of

Tunstall in the 18th century,” Steve continues. “This included Holly Wall

Farm and Tunstall Farm at Clay Hills, north-west of Tunstall. We know that

in 1830 Tunstall Farm was in the occupation of a Mary Younge and the land

on the east side of the farm was in the ownership of the Smith Childe

family of Newfield Hall. Seven acres of Tunstall Farm were sold to Mr

Robert Williamson, coal and ironmaster, who opened Goldendale ironworks

with his brother Hugh Henshall Williamson in the 1840s.”

In addition to the regularly apportioned Anglican, Catholic and

Non-Conformists, there is these days, a delightful corner that is being

used by Tunstall’s large Muslim community; evidence of the town’s cultural

assimilation even when life is done.

the graves of Father Welch and Father Ryan

“The Catholic quarter is headed by two famous priests, Father Welch and

Father Ryan. Ryan was held in great esteem throughout North Staffordshire.

Legend has it that when he died in 1951, his funeral procession was five

miles long bringing the district to a stand still in an amazing show of

respect and affection. His genius seemed to be in getting the community

involved, a tribute to his energy in constructing the inspiring Church of

the Sacred Heart in Queens Avenue Tunstall.”

Another special resting place is that of Hortense Daman Clews, a wartime

heroine and concentration camp survivor who received many honours for her

bravery during the Second World War.

“As a child of 13 Hortense was working for the Belgium Resistance as a

go-between behind the lines in her home town of Leuvan and giving

shelter to allied airmen,” explains Steve.

“In 1944, her family were betrayed and Hortense was sent to the infamous

Ravensbruck concentration camp where she was subjected to many bestial

privations. Liberated by Russians, Hortense made her way back home where

she met her husband, Sergeant Sydney Clews, from Tunstall. The couple

married and came to England in 1945, Sydney died in 1994.”

Hortense Daman Clews

![]()

![]()

![]()