|

Bentilee - 'Sunshine

Houses'

I almost went to live in Bentilee in 1960 but the sitting tenant was unable to move for some reason or other. It’s quite possible I could have been born in Bucknall for that is where my grandmother escaped to in the first wave of slum clearances from Hanley following the demolition of Back Gate Street where my mother was born. This unpleasant alley has been long buried somewhere under the top of Bucknall Old Road. It sounded a squalid place by all accounts with reported tales of open sewers, communal water taps and latrines although no one ever told me how truly bad it must have been living there.

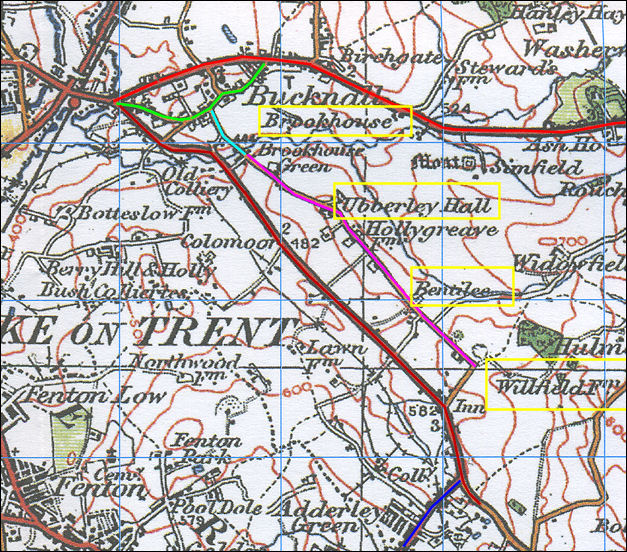

Bucknall takes its name from Bucen-knoll

– a prominence with beech trees. The region was once owned by Lord Verdon of Alton Castle who also occupied an ancient stone mansion known as Ubberley Hall. Bertram de Verdon was Lord of Ubberley and the founder of Croxden Abbey in the reign of Henry II, while in the time of Elizabeth I, Thomas Bucknall was the principal owner. During the Industrial Revolution the Ridgeway family introduced coalmining across the land where the Bentilee estate stands today.

houses in John Street,

Hanley - built 1807

- demolished as part of the slum clearance -

Photo: "Potworks, the

industrial architecture of the Staffordshire potteries"

Slum housing in Hanley

had been tolerated for a generation as people lived dangerously next door to where they worked. But by the middle of the 1930’s government introduced forceful legislation to make local authorities accountable for slum clearance. In central Stoke on Trent alone there were 3,740 cases of severe overcrowding. In 1938 the council made 3,877 compulsory purchase orders on poor quality houses but then the war called a halt to any further progress.

In the 1950’s the council acquired Bentilee Farm and Ubberley Farm and here the largest council estate in Europe was built – a new town with 2,586 houses and a population of over 7,000. It was a brave new world as whole communities from Hanley and Longton moved across the city. Even in 1956 records show there were still 10,800 Stoke on Trent properties deemed unfit by modern standards – and the people kept coming to Bentilee in their thousands as the new community swelled.

Map of the Bentilee area

c.1922 - before the housing estate was built

The head of retired miner Idwal Thomas Bowen

looks like a sculpture sliced from a lump of coal. Closer scrutiny though reveals the icon to be actual living flesh. And proof lies, if testimony is needed, in the 82 year-old impish, perpetually-smiling face and electric-blue eyes – Idwal Bowen, the man, is made of coal. He came to the Potteries from the Rhondda Valley in 1954 to work at Hem Heath. In 1968 he moved his family to Bentilee. “I took to it at once,” says Idwal. “They were called ‘Sunshine Houses’ on account of the living room having a window at each end.”

For a man who’d spent much of his life in gloomy pits the new house must have been a revelation. Here the three main roads travelling through Bentilee each follow the line of the ancient Dividy Lane. The entire estate was intentionally laid-out to settle across a south-west drift inviting the sun to spill its light simultaneously into both front and back gardens.

The window frames of post war semis were made of metal making the rooms cold in winter and susceptible to damp. Idwal remembers the cold. “When I was young my father swore by gas lighting. People coming into Bentilee at first found coldness a problem and regretted the loss of gaslight. Gas mantles provided meagre warmth you see?”

I could see the correlation at once for these relocated tenants had arrived in Bentilee from terraced darkness deficient of useful windows, where fossil fuel and double-brick constructions provided all the warmth a family needed.

The new estate was airy and fresh – perhaps a little too open for those accustomed to claustrophobic alleys and dark backs. But it was the gardens that provided the greatest advance – the small piece of productive soil that belonged exclusively to the family – a place to relax and watch the day pass by.

Idwal remembers the back-to-back coal fire where the built-in boiler gave sufficient warmth to provide heat for cooking on the kitchen range flipside to the living room fire. Novel as they were you’d be hard put to find one of these in Bentilee today for most were taken out to make way for modern cookers and central heating. But even more innovative was the upstairs en-suite bathroom and the tiny downstairs lavatory next to the utility room. This indeed was luxury personified!

looking down Dawlish

Drive towards the 'top shops' - in the middle is the tower of St.

Stephen's Church

photo: 1968 - Ken &

Joan Davis

Into the new estate came community centres. The Ubberley and Bentilee Workingmen’s Club came first. But the estate was so huge that dislocated miners got so fed up of walking the wearisome distance that they built the Berry Hill club at the top of the estate for themselves. Then the Harold Clowes Community centre was established right in the middle.

The first people in Bentilee had experienced nothing like it arriving like aliens from another country. Resident and councillor, John Davies, has produced a significant film of interviews with some of these Bentilee pioneers providing a fascinating piece of local history. It is appropriate to remember that Bentilee wasn’t occupied overnight. The first arrivals had to live for two years on an active construction site with ankle-deep mud and clay as a common element.

The newcomers remembered impassable streets

looking and feeling like quagmire when it rained. Plots of land for each garden were unmarked so people erected fences as they wished literally starting from scratch after the gold rush. One female interviewee tells of searching for her new house and being misdirected by a builder himself an innocent at large. She arrived with her friend and previous neighbour each looking for a different street name. After a couple of hours searching by themselves they met up to find they were once again next door neighbours each connected on the same corner of two different streets.

People changed shoes twice each day and took a spare pair when they went to Hanley. It was so bad that it took the milkman all day to reach his last delivery by 5pm. To catch a bus involved a walk through the mud for over a mile to the nearest bus stop. Another interviewee arrived with her furniture on the back of a coal lorry, “It took hours just to travel up Winchester Avenue to the new house,” she said. “The lorry kept getting stuck. Then as soon as we got in the house we were marooned in the mud and couldn’t go through the door.” Young mothers tumbled trying to negotiate pushchairs across the road and many a pair of shoes were lost to the swampy embankment of the sylvan brook that flowed right through the estate. But the children loved this huge adventure playground where copse and spinney replaced backyards and dead-end streets.

With the new residents came the door-to-door salesmen arriving in their dozens with bedclothes, carpets and household goods. As you would expect items were paid for by instalment with many defaulters avoiding the collectors by pretending to be out. As one of John’s contributors ironically put it, “This was the time Bentilee became known as Dodge City.”

“Eventually things fell into place,” explained John. “A central shopping area was established at Devonshire Square with a Woolworth’s store, a Boots and a Tesco and all the peripheral services. But as with most towns these big shops have moved away to industrial estates and centralised shopping areas.”

I asked John about Bentilee’s criminal reputation. “It’s been overplayed and exaggerated,” he said. “Bentilee has an undeserved stigma. One reason is that it is such a large district with a concentrated community so it obviously reveals a higher proportion of crime. There’s no more crime here than anywhere else – it’s just the concentration that reflects it.”

Nevertheless he concedes that Bentilee is still the most deprived district in Stoke on Trent and lies in the bottom 14 of dispossessed towns in England and Wales. But John is brimming with optimism. “A new project for Bentilee is being started this year to be completed in 2006. It will be the most modern, holistic one-stop project in the city. A walk-in health centre including ophthalmic and dental services is planned. Advice agencies will have a permanent presence along with social services and housing departments, youth facilities and retail outlets including the current shops. The Bentilee project will be a ground-breaking initiative and used as a model by the government for future community projects.”

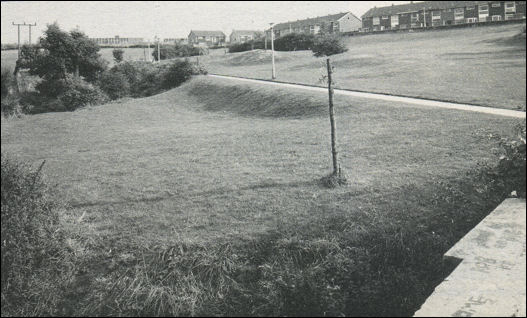

Bentilee valley after

reclamation and housing development

But for my money the most unique and exciting thing about Bentilee is its environment. Here is a giant council estate sprawled across the middle of the countryside with views of heather-capped hills overlooking babbling brooks and rolling fields. These are the views that Idwal Bowen, John Davis and their neighbours look out on each day, the same landscape that was seen by Lord Verdon, Thomas Bucknall and the Ridgeway’s. How I envy them all.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()

![]()