|

Hartshill - 99% of us will visit

Hartshill Bank -

Stoke-on-Trent

looking down into Stoke

There was a time when it was essential to have a bit of class to live in Hartshill. But to be buried there you really had to mind your place.

The decision to provide a new municipal cemetery for the borough of Stoke was made in 1881. One of those in the forefront of its planning was no less a celebrity than Colin Minton Campbell. Nearly four years later the 15 acre site was opened on the western hill slope of Hartshill. Many people had made instant objections to the proposals saying that it was too far from Stoke town.

But worse still, there were mutterings over the number of chapels planned to accommodate a variety of creeds. Campbell was mayor and the richest and largest employer in town. Putting down a donation of Ł500 he insisted that the cemetery should be laid out in an ornamental style marking it not just as a place of interment but a resort where people could promenade and marvel at the fine memorials. Colin Minton Campbell further stipulated that his family should have first choice of land and those who came to be his neighbours in death should be laid-out according to hierarchy and class.

I suppose if the richest potter in Stoke was to be buried there he was going to make sure he didn’t lie alongside the hoi polloi.

Two symmetrical Chapels

at Hartshill Cemetery

The two chapels, Nonconformist on the left and Church of England on the

right

The dispute over the number of cemetery chapels was resolved after months of public debate with readers of the Sentinel lining up on both sides. Worried about how the cost would affect the rates some correspondents supported the provision of one chapel available to all religious denominations while the churchwardens of St Peter’s promoted the idea of two chapels, one for, what they termed bona fide church people and another for dissenters.

Campbell, himself a prominent member of the Anglican Church, supported two chapels. Two chapels it was then. The final decision was taken by town councillors without any consultation with the ratepayers. It’s unlikely that this sort of procedure would happen these days – isn’t it?

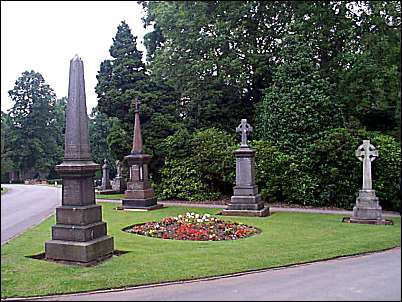

The imposing memorial of Colin Minton Campbell

in the 'best' area of the first class CoE

The imposing memorial of Colin Minton Campbell stands adjacent to the main entrance erected after his death in 1885. After her husband’s death Campbell’s wife, Louisa, converted to Catholicism and in accordance with Campbell’s rules was buried in another part of the cemetery where a rather droll epigram on her memorial insinuates ‘nearer my God to thee.’ Louisa’s grave, out of sight of her husband, stands in the catholic section just in front of the memorial to Louis Marc Emmanual Solon the famous Minton’s pottery artist who invented the process of pate-sur-pate respected as one of the most inventive artists ever to work in Stoke on Trent. Nearby is the grave of Leon Arnoux another equally renowned Minton’s artist.

The first class Roman

Catholic graves

including the graves of Louisa Campbell, Marc Solon and Leon Arnoux

Louisa Wilmot Campbell

Widow of Colin Minton Campbell

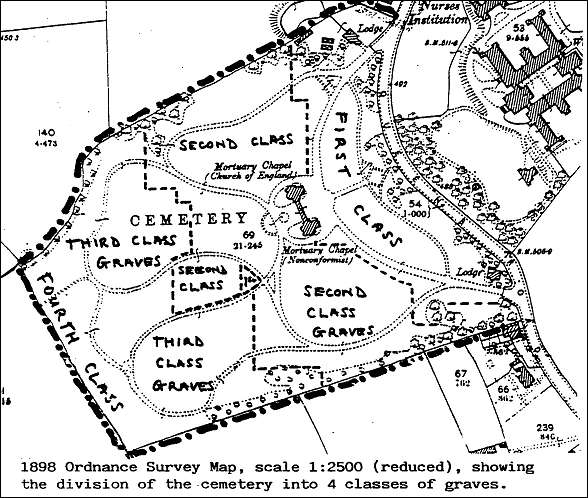

Hartshill cemetery is situated on Queen’s Road and is laid out in four distinct ranks – the first class accommodation holds the remains of Colin Minton Campbell. The second class is a little lower to the west where in order to get near to the top table the pre-deceased could acquire a choice of plot for an appropriate fee. Further down from this level there is a distinct demarcation between the 2nd and 3rd class zones specifically marked so that the earth of the upper-classes would not be seen mixing with the soil of their inferiors.

Third class corpses had no choice in their allocated plots – nor are many of their resting places marked with headstones as their relatives just couldn’t afford the expense. Very quickly the third class area became full. Even so the authorities wouldn’t allow the overspill to trespass onto the upper class land. The remedy was to purchase additional land to make a fourth class sector where many paupers, workhouse and hospital internees were buried.

Map showing division of

the cemetery into 4 classes of graves

North Staffs Royal

Infirmary taken in c1975

Hartshill is the Alpha and Omega of Stoke on Trent. At one frontier women come to give birth at the region’s central maternity hospital while at the other boundary the public mortuary skulks waiting for the clock of life to reach midnight. The civic inquisitor, the office of coroner, sits rather neatly in between. However Hartshill is a place of healing as well.

The first hospital here was Stoke on Trent parish hospital erected in 1842 to accommodate patients from the nearby workhouse. The infirmary was opened in 1870 with room for 145 beds. In 1894 a so-called ‘lunacy’ section was added and by the end of the Edwardian era the whole site had grown dramatically including an onsite fire station and nursing school.

According to its website the University Hospital Trust of North Staffordshire today is one of the largest acute hospitals in the country and the Health Authority serves a population of half a million. Last year it saw 77,000 in-patients, almost 36,000 day cases, over 103,500 new outpatient referrals, and over 261,000 outpatient follow-up appointments. In total, it handled almost 130,000 emergency attendances with 90,518 coming through the Emergency Department. The Hospital has 1,377 beds and in total employs 6,700 staff, with more than 129 consultants.

Hartshill is full of activity though mainly with blocks of moving traffic which I suppose is symptomatic to a village which 99% of us will visit at least once in a lifetime. The shops are neat and cover the purchase of most provisions.

Moore’s Metals on Hartshill Road

At the west end, near the border with Newcastle, the oldest business in town is situated. No not a grocery, not a news agency or an accountancy, but a scrap metal yard – Moore’s Metals. The sole proprietor of this famous establishment is Philip Moore whose grandfather started the business here in 1911.

As you would imagine the history of scrap metal collection is highly colourful and Moore’s business reached a high peak under the ownership of Philip’s father, Charles. “I suppose my father took the trade to a higher level,” said Philip. “He was passionately interested in horse racing and there’s no doubt his horses provided a good secondary income. Most racing punters in the Potteries will remember the legendary handicapper Moore’s Metal. My dad was horse mad. I’ve no interest myself.”

The walls of the office carry a number of photographs of winning horses with grinning jockeys, beaming owners and smiling punters. To me scrap metal men with pockets full of ready cash standing in racecourse beer tents with their camp followers to hand have always seemed symbolic of another age – an age of simple opportunity where local Del Trotters scored and won and lost again.

The Moore’s family of seven brothers came from Ireland at the beginning of the 20th century and were quite literally rag-a-bone men. For many years a lucrative sideline was the collection of rabbit skins thrown out of meat markets after the butcher had skinned the carcass. The brothers cleaned the pelts and sold them to furriers who fashioned them into coats. But it was with the introduction of recycling and skip collections in the 1960’s that the business really came to thrive.

“I remember my father working with a three-man sledgehammer where two men would hold down the object,” explained Philip, “and the other would manually throw the one-ton hammer onto it. It was very dangerous work.”

These days 90 percent of Moore’s metal is baled on site and shipped overseas. “It used to all go to Shelton Bar – but, well you know what happened to the British steel industry. Now, in Turkey for instance, our scrap is processed into sheets and sold back to the UK.”

Along with horse-drawn ice cream carts and scissor grinders the days of the old rag-a-bone men are gone and gone forever. And the scrap metal business has succumbed to globalisation and is run by very experienced business persons. Philip is the perfect example of enterprise.

“I was educated at London University and became a qualified solicitor,” he nods convincingly. I also studied to become a priest for two years but instead of being called to the altar I was called to the scrap.” I smile at the thought of a dog-collared priest with a handcart calling out rag-a-bone along cobble-stoned alleys –

impressive!

a new frontage hides the old cinema which was once the famous Victoria Theatre

Hartshill is full of contradictions. Across the road from the scrap yard is Nixon’s Garage a business which still uses the same building that was once a famous snooker hall in the 1930’s. And on the corner of Victoria Street a new frontage hides the old cinema which was once the famous Victoria Theatre after a short spell as a nightclub in the late 1960’s. It’s here that many potters were given their first introduction to the smell of greasepaint in Stephen Joseph’s style of theatre-in-the-round under the direction and production skills of the legendary Peter Cheeseman.

On the other side of the road a building site climbs to reach the sky with houses and apartments for medical staff. No need these days for doctors and nurses to compete for hierarchical position for, unlike the Victorian cemetery where class counted even after death, tenancy for the living is based on needs and not status.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()

![]()