|

Sneyd Green - if you go down the wrong street you’ll miss

it

The road from Chell to Hanley is a little fraught with complex traffic obstacles. After Smallthorne Roundabout strangers may be forgiven for thinking things couldn’t get any worse. But a mile further on and Sneyd Green crossroads is the devil’s own conundrum. Somebody should drop a bomb on it! Oops!

Sneyd Green is one of the oldest places in the Potteries and its traffic management illustrates this as cars, buses and pedestrians fight for the last inch of available space clinging to chaotic turning spots in the middle of the road as traffic whizzes crazily by.

I blame it on the monks of Abbey Hulton for this was the junction where one group marched off to Chell and another to the grange at Cobridge. If these hooded pilgrims had chosen a route around the hilltop instead of going over it Sneyd Green crossroads would today be a pleasant oasis with expansive views.

But we are inheritors of a millennium of idiosyncratic routes. You and I – and the road planners – blindly following the fold.

Originally High Lane stretched from Chell to Sneyd Green. The Audley family, those rich Norman landowners, once hunted wild boar along its western slopes all the way into Burslem and to Bradwell Wood. The road, that is Hanley Road, became a turnpike in 1770 and in 1832 the increase of traffic influenced the extension directly into the Hanley Greens – and the descent to gridlock had begun.

In the 1960's Sneyd Green gained a reputation for being the noble end of Burslem. Here the town’s professional classes came to reside, professionals like former teacher and local historian Elaine Sutton. Elaine has lived near Hanley Road for 28 years. The previous occupier of her home was Stoke City and England football legend George Eastham.

“I chose to live in Sneyd Green because of convenient access,” she tells me. “Although mine is a secluded property it is nevertheless very central to the community.”

Elaine remembers bringing her children up in activity play areas at the nearby Sneyd Arms. But over the hill and further east down from Milton Road is the other end of the district, a completely different community which Elaine never visits.

“Sneyd Green is comprised of a number of different zones,” she considers, “the old Sneyd, the residential Sneyd and the Holden Sneyd. They might as well be a million miles apart.”

a date above the door proclaims that

this farmhouse stood here in 1736

photos: Aug 2008

Former boss of the Institute of Ceramic Research Association, Roy Harrison, was born in Sneyd Street, the old part that is; and has lived in the same house since 1933. A date carved above the door proclaims that his farmhouse stood here in 1736 but Roy believes it originates in a much earlier time. The ceilings are oak-beamed throughout and there used to be a bread oven with ancient fittings over an open fireplace.

“There is a mark on one of the beams,” indicates Roy, “with the number 166 and something else which is obscure carved into the timber. This date actually fits in with the architectural design and with the age of the brickwork.”

So, I ask, in the 1600s was Sneyd Street the heart of Sneyd Green?

“There was a cluster of cottages. All around was farmland and it was like that when we moved from our lower cottage which the Briggs family moved into after we left.”

Roy reminds me of the discovery of medieval kilns which were unearthed by school children in the 1960s.

“I’ve dug up many boxes of broken medieval ware myself which I’ve handed over to the Potteries Museum,” he confides, Al these important excavations serve to confirm that potting was an activity here certainly before the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. The small Sneyd Green farming community stayed behind after the monks left.

the Old King and

Queen Inn, Sneyd Street

an photo of the Old King and Queen shows a bull baiting ring

set in the floor in front of the inn

It was here that bull-baiting became a popular pastime in the early 19th century. A cottage opposite Roy’s farmhouse was, until 1903, the Old King and Queen Inn. Not so long ago a metal ring could be seen anchored to the inn’s forecourt to which the unfortunate animal was tethered as men came from near and far to pit their bulldogs in a bloody one-sided battle.

So brutal was this spectacle that local poet, Noah Heath, wrote narrative poems condemning the bestial sport. Heath, a Methodist preacher, was born in Sneyd Street in 1780 and witnessed this slaughter in the name of sport. Judge for yourself the reality of his observations:

‘With yelping and shouting, “Now, Toss,” is the cry,

’Till the noise of the vulgar ascends to the sky.

“Toss” misses his hold, and aloft now he goes,

For vengeance now falls on the innocent foes;

His belly ripped open, and from the death wound

His warm smoking entrails now fall to the ground.’

“When I was a boy our farmhouse stood further back off the road circled by fields,” reveals Roy as we explore his wonderful overgrown natural garden filled with wild woodland flowers and shrubs.

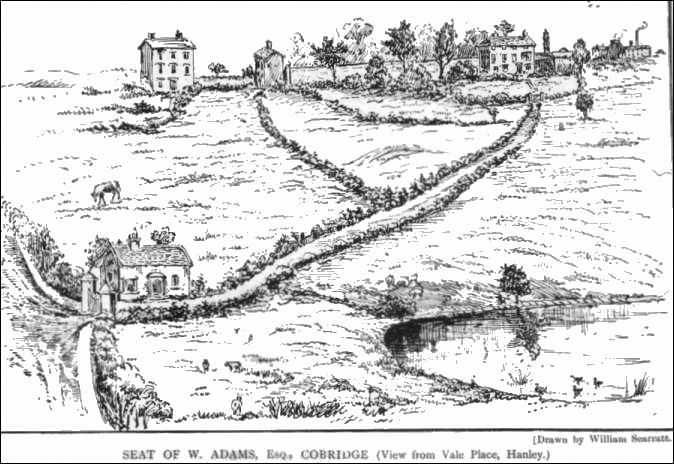

Seat of W. Adams

Esq., Cobridge

From "Old Times in the Potteries" William Scarratt

1906

“Over the ridge opposite was Cobridge Hall the home of William Adams,” he recalls

The famous potter in fact purchased some of Sneyd Green’s fields in 1769. Ten years after this, industrial success enabled him to knock down a few redundant buildings to make space for his lavish mansion which itself succumbed to industrialisation in 1913 when it was demolished to make space for a pot bank. There was a long drive from Vale Place to the hall which was situated some 300 metres on the south side of Sneyd Street. Most of this land is now occupied by the tumbling meadows of Hanley Forest Park.

“That side was known as the Hollies,” explains Roy. “I can remember cattle grazing and sheep flocking over the whole of the hillside. Jenks’ Farm was on the other side of the road. Across the lane there was another farmhouse with a huge pear tree in the garden. And there was a duck pond and from there you could see all the way to Leek New Road.

I remember the Co-op dairy was being built when I was a boy. Now that’s gone replaced by houses. At the top of the street there was a little cottage – as small as the smallest house in the country – the famous one in North Wales. They knocked the cottage down in 1960. Scandalous isn’t it?”

Those who are familiar with the narrow winding contours of Sneyd Street may find it hard to believe that it was widened in 1926 though it’s hard to see where. And also, believe or not, there is a pile of sandstone in Roy’s back garden which is of a similar material used in the construction of Hulton Abbey in 1223.

“How it got here will always be a mystery, but I suspect it was carried here by the monks travelling to Burslem Grange,” he declares.

Another Roy, Roy Briggs, of the family who moved into Roy Harrison’s vacated cottage when they moved higher up the street, is also an original ‘Sneyd Greener.’ Not only was he born in Sneyd Street he, as a boy, went to the same school where he ended his career as its head teacher. Roy, now retired, still remembers his village with conspicuous memories.

“There’s been a Briggs in Sneyd Street for generations,” he informs me, “and a Briggs at the school since 1913. But our family was as poor as church mice. We first lived next to the Old Bull’s Head pub and had an outside lavatory and a cold water standpipe that served three houses.”

Roy Briggs is the youngest of nine children. They bred big families in those days not particularly because of the unavailability of contraception but for gainful reasons as well. Roy was able to have a better education because the wages of the elder siblings helped finance the youngest. But Roy repaid his brothers and sisters handsomely and in full with the accomplishment of his outstanding teaching career.

Here in Sneyd Street Roy’s grandparents – a family named the Tudors – lived in another tiny cottage.

“You wouldn’t believe how small it was,” says Roy. “It had one room and a tiny kitchen at the back and a thunder-box toilet in the yard. The front door was a set of wooden strips with a latch – no lock. My grandfather Tudor worked on a pot-bank, but he was a self-educated man who took on many important positions in the church.

By contrast his wife, Sarah, was a drunkard – oh yes she was! She was forever going off to the pub and carrying back a jug of ale. My grandfather used to wait for her outside calling through the pub door – ‘Are you coming out of there Sarah or am I going to have to come and fetch you again.’ The good old days eh? In the evenings grandfather would gather his children around him and tell them stirring Shakespearian stories in Shakespearian language. Imagine that?”

Roy Briggs remembers nearby Cobridge as high and mighty dozing snootily in the summer sun, gazing snootily across the lower reaches of Sneyd Street.

“The higher up Sneyd Street you lived the posher you were. Just above grandfather’s cottage there was a little isolated village. There must have been some three-hundred pottery workers living here once. We moved into Roy Harrison’s house after his family moved up to the well-to-do end. Ladder of social ascent I suppose.”

I speculated that the geographical centre of Sneyd Green was formerly located at the bend half way along Sneyd Street. After all here were the old inns, the farms, the village blacksmith and the duck pond – everything you would imagine a typical village green would look like.

In 1940 the German Luftwaffe nearly demolished Roy Harrison’s house when a bomb was dropped on this spot creating a huge crater. The two friends, Roy Harrison and Roy Briggs dressed in baggy-trousers, went to look at the hole but seeing nothing of particular interest sullenly withdrew as schoolboys do, their attention diverted elsewhere.

Sneyd Green is full of history but I warn you, if you go down the wrong street you’ll miss it.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()

![]()