|

Bagnall still retains a strong Elizabethan

quintessence

For those who may have forgotten in the aftermath of its manufacturing decline, North Staffordshire was once a heavy industrial district. Without its natural mineral resources and the human means to utilize its coal, its iron and clay, it is difficult to imagine what the district might have looked like before the land became polluted and reclaimed.

History tells us that the 30 square miles area of the city originally comprised of isolated moorland settlements:

‘a palimpsest,’ as the Victoria County History describes the northern tip of the Pirehill Hundred, ‘whose original parochial pattern has been overlaid by a complex of civic government.’

Nicely put I reckon.

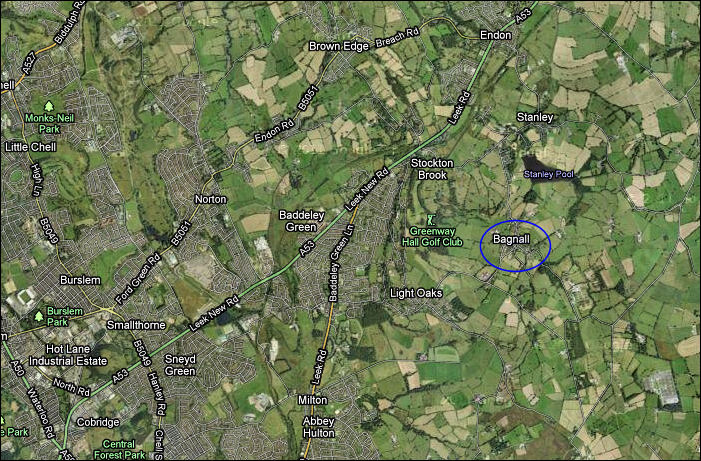

the location of Bagnall

in relationship to some of the Potteries towns on the left of the map

Bagnall village

Google maps - June 2011

St. Chad's - the parish

church of Bagnall

A significant milestone of community management came with the administration of the poor relief during the reign of Good Queen Bess; that is Queen Elizabeth 1 in the year 1601. Stoke, the town that is, was divided into eight chapelries, the furthest-flung being Bagnall which had the same status as Hanley until the poor relief law was placed under the control of a Select Vestry in 1816.

Before this, during the time of the Civil War, Hanley and Shelton together were rated as being minor chapelries to Bucknall and Bagnall. This in its own right provides economic evidence of how, since that time, industry has spectacularly changed the face of North Staffordshire.

Bagnall today still retains a strong Elizabethan

quintessence, and it is noticeable in some of its buildings. Examples are the village green that stands central which is edged by a 16th century inn. Nearby are the parish church of St Chad, built commencing 1834, and the modern village hall. But perhaps the most prominent building in the village is Bagnall Hall where you half expect at any minute to make way for a charging stallion and a rider to arrive carrying the royal mails. It is here that I meet Lynn Vincent and her son Philip whose family are the hall’s current lucky owners (2006).

“We came to live in Bagnall in 1978,” says Lynn, “when we moved into the barn which once probably stood in the hall’s grounds.”

It was in this lovely converted workplace, and now a modernised country house, that Philip was born those many years ago.

“I’ve loved Bagnall since I was a child,” he tells me in the clipped tones of a manorial lord. “Went to school here and at Endon; all my old friends are from the area. The family bought the hall a few years ago and I’ve recently started to renovate it to its original period.”

Bagnall Hall - a Grade II

listed building, situated in the centre of the village, near the Stafford

Arms

Working in the hall, spoke-shaving the contours of a piece of English oak panelling, is 65 year old carpenter Gary Barker.

“Me! Well left school at fifteen and was taken on by the notable Potteries’ builder Charles Cornes on a seven year apprenticeship,” says Gary diffidently.

This man, Gary, is a master craftsman who worked when he was a young man on the restoration of Hanley’s Theatre Royal in 1951 after a devastating fire razed it to the ground. His skills in the refurbishment of Bagnall Hall are self-evident as he labours on the aged timbers and on the renovation of the original architrave mouldings.

In this discreetly antiquated building, on this day of sunshine, the entrance lobby is illuminated by coloured shafts of sunlight tumbling across the staircase from the restored leaded-lights. Original timber uprights from the old hall have been reused and now support the low ceilings beneath which space tiny doorways sit to guard minor entrances, built not for fashion but for utility. These doors lead to a myriad of service rooms, one of which opens into the lovingly restored drawing room. Here sash-cord casements descend from ceiling to floor where window seats once lodged demure and lovelorn maidens who you can imagine gazing across misty orchards reciting poems from leather-bound anthologies while high trees rustle in the wind.

Indeed it is true that the Keat’s family occupied the hall on the turn of the 19th century – not the poet John Keats of course, but an engineer, his wife Hannah and their children, one of whom, Ann, left to become licensee of the inn that stands at the edge of the green.

At the front of the hall, Philip points out two dates carved above the upper stone lintels – 1603, one announces while the other reports the date of rebuilding in 1777.

“Naturally I have made some research into the house,” Philip notes, “but there is still much to do. A lot needs to be followed up, for it seems the hall suffered extensive damage after the later date and many of the documents have disappeared. These could tell me a lot as to why the alterations and changes were made. You can see that from an etching I have.”

He produces this picture which shows a much larger building that includes an extra wing which would have doubled the size of the house now standing. The picture of the missing north wing depicts a lofty clock tower on top of a mansion that would not be out of place in a prominent central position in an important shire town.

“Once,” continues Philip, “there were seven bedrooms and servants quarters. It goes back to Elizabethan times having been built in 1593 by a justice of the peace, one James Murrall who was knighted by Charles I in 1631. See, there are his initials over the doorway – J. M.”

We wander into a modestly laid out garden and encounter a well the mouth of which is covered by a wooden board. Moving the cover Philip drops a stone into the opening. “Count!” he commands. It takes five seconds to strike water. “That’s a long way down.”

St. Chad's House on the corner of The Green and

Spring Bank

Around the corner from the hall in Spring Banks, live Bagnall-born Kenneth Simpson and his wife Suzanne. The views from their south-facing window are spectacular opening across the valley down to the eponymous Bagnall ford and the springs.

“As a boy I recall going to Bagnall School just up the road,” says Kenneth. “There were two classes then and the school had a register of 30 pupils. Bagnall had its own police constable and a cottage hospital. These were golden times for me spent in adventure at the hall with children of the then occupiers, a family whose name was Lord.

The village of my childhood was truly rural. In summer we watched as coach loads of children were brought up from the Potteries for picnics on the Green just so as they could get a breath of fresh air. These were children of miners and potters – poor beings who lived without fresh air in the smoke and dust of industry – pale face kids that always appeared undernourished.

Bagnall post office was open then; it was a grocery shop that sold everything and a very popular tuck shop for local kids. There were two village women who laid out trestles and served cakes and sandwiches to visitors – Mrs Goodall and Mrs Fisherwick their names were who challenged each other to see who could brew the best tea.”

Suzanne, originally from the village of Endon, married into Bagnall village and Bagnall village life.

“Life was so different. We worked and we played at a much slower pace and we didn’t worry about getting a bit dirty. Walking along the lanes through cow muck was commonplace – I miss it, and I miss the smells of a farming community – I miss the earth smells and smells of haymaking. I absolutely adore the English seasons of my childhood. In winter we’d often be snowed-in and cut off from the rest of the world. There’s a famous Sentinel photograph showing the snow drifts in Bagnall high above the houses. The photographer was one of the first to get up here in that bitter winter of 1947. Do you remember Ken?”

Kenneth remembers there were six farms in the community when he was a boy. “Now there’s only one,” he murmurs a little sadly.

In the 1950’s there were 600 Bagnall people on the census register now that figure has been doubled due mainly to boundary changes.

“But today a new community is coming to Bagnall,” Kenneth confides. “Bagnall is still a beautiful village and largely crime-free. And only people with money can now afford to live here. Its closeness to Hanley for shopping and workplaces make it attractive to the rich. Villages like ours, like Bagnall, are fast disappearing from the English landscape simply because people who work in the city want to live in the country. And who can blame them.”

The Stafford Arms - the

public house - 'central to any rural community'

Bagnall has its village hall and its own parish council; even its own website. But central to any rural community is its public house. The Stafford Arms has been a popular attraction for the whole of Stoke-on-Trent as far back as the 1960s when the hostelry acquired a reputation for good beer and, more tantalisingly, as a risqué convenient romantic rendezvous with a lenience toward courting couples. Even the implementation of the breathalyser legislation in 1978, which adversely affected the patronage of most country pubs, seems to have the opposite effect on the Stafford Arms – but perhaps that was because the Stafford Arms was very popular with the city police! The licensees in those days were Doris and Harold Wyatt who provided good wholesome food fare as well as a decent pint and a haven of discretion.

This affectionate old pub has undergone many structural alterations – the barn is now a long lounge and the rear restaurant extension retains it erstwhile popularity. However, the tiny rooms surrounding the main entrance, known to Bagnalian Kenneth Simpson as either the cuff-and-collar room (for the well-to-do customers) and the farmer’s room (for the regular labourers) have fallen to the fad for open-planed modernisation.

Claire Collins and Andrew Pegg have been the tenants for the past three years and now see themselves as villagers.

“We’ve tried to provide for both villagers and for visitors with home cooking, and the pub had remained popular with outsiders. There is a local men’s night – men from the village who just sit and put the world to right – as in any traditional English pub,” says Claire.

Nevertheless, a much appreciated and valuable connection with the past remains in the presence of Claire’s assistant, Brenda Taylor, who worked all those years ago for Doris and Harold.

“Once I worked for Parker’s Brewery in Burslem,” Brenda reminisces somewhat vaguely. “Then I came to help Doris and Harold when they moved in. I could tell you some stories from those times....” But she hesitates, her eyes sparkling as they wordlessly shuffle through a collection of what are no doubt amazing, but unrepeatable recollections. And I hoped she would tell me just a few – but I hoped in vain. These are country tavern tales and they shall remain confidential for they are whispers of another age. And that is another reason why I find the lovely village of Bagnall such an attraction.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()