|

The "Grand Cross"

of canals:

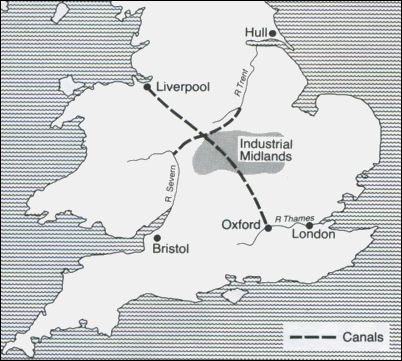

The map below shows how a waterway

from the east coast to the west coast of England would link up the

important ports of Hull and Liverpool.

James Brindley had a plan to join the Mersey to the Trent and the Thames to the

Severn. When these two systems were linked up, a 'Grand Cross' would

be formed, providing a canal system between London, Liverpool,

Bristol and Hull.

The 'Grand Cross' - a canal system between

London, Liverpool, Bristol and Hull.

The Runcorn extension to the Bridgewater Canal had been built

with the idea of joining it up to a future canal linking the Mersey

to the Trent.

Josiah Wedgwood, the wealthy factory owner, was willing to

provide money for the canal because he owned a pottery at Burslem,

Stoke-on-Trent and needed a way of getting Cornish china clay to his

works. A meeting was held in Staffordshire in December 1765:

"Mr Wedgwood and many other important

gentlemen were present to take part in the proceedings. Mr

Brindley was called upon to explain his plans. He did this so

clearly that it was clear to the dullest person present what he

meant.

It was decided that steps should be taken to apply for a bill in

the next session of Parliament. Mr Wedgwood put his name down for

£1000 and promised to buy a large number of shares.

The promoters of the plan proposed to call the project 'The Canal

from the Trent to the Mersey' but Brindley urged that it should be

called 'The Grand Trunk because other canals would branch out from

it at various points of its course."

An Act was passed giving permission for the building of a canal

on 3 May 1766. Samuel Smiles wrote:

"There

was great rejoicing at Burslem on the news arriving of the passing

of the Act. The first sod of the canal was cut by Josiah Wedgwood.

It was a great day for the Potteries as the event proved. In the

afternoon, a sheep was roasted whole in Burslem market place for

the good of the poorer class of potters.

Wedgwood was most impressed with the

advantages of the canal. He knew how much his trade had suffered

as a result of poor roads and rivers and how it might grow if a

canal joined Liverpool, Hull and Bristol. On the banks of the

canal he built the famous Etruria Pottery Works, the finest

factory of its kind. Near the factory he built a mansion for

himself and cottages for his workpeople."

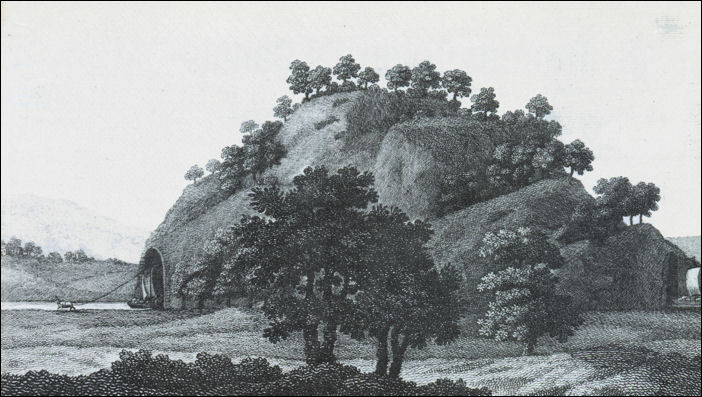

Brindley had stated that the new canal would be finished by

December 1772. But the work was held up by problems in digging a

tunnel through Harecastle Hill, west of Stoke-on-Trent. When

Brindley revealed his plan to drive a tunnel through the hill, many

people thought he was mad. The tunnel was over 2.5 km long and it

took 11 years to build.

All the work had to be done by hand. The workers or 'navvies'

used pick-axes and shovels for digging, candles for lighting and

dynamite to break up the rocks.

|

The tunnel became famous as an

engineering marvel. One merchant wrote:

"Gentlemen! Come and look at the eighth wonder of the world,

the underground canal which is the work of the great Mr

Brindley. He handles rock as easily as you would handle plum

pies. He is as plain a looking man as one of the peasants

of the Peak or one of his own carters. But when he speaks,

all ears listen and every mind is filled with wonder at the

things he says are possible. He has cut a mile through bogs

which he binds up, embanking them with stones which he gets

from other parts of the canal.

On the side of Yelden Hill, he has a pump which is

worked by water and a stove which sucks through the damps

which would otherwise annoy the men who are cutting towards

the centre of the hill. He cuts the clay which he uses as

bricks to arch the subterraneous parts. We would like to see

the canal finish at Wilden Ferry when we shall be able to send

coal and pots to London and to different parts of the globe." |

Unfortunately Brindley never saw the tunnel or the canal

completed. He became ill from diabetes and died in 1772. His

brother-in-law, Hugh Henshall, carried on with the work and the

tunnel was finished in May 1777. There was no towpath through the

tunnel, so the bargees had to push the barges along by lying on

their backs and bracing their legs against the tunnel walls. This

was known as 'legging' and it was very tiring.

The Trent and Mersey Canal, and others which followed, brought

enormous benefits for industry. Thomas Bentley, a friend of Josiah

Wedgwood, wrote:

"The most obvious effect of the new canal is that it cuts

the cost of sending goods and opens up an easy way of getting from

the distant parts of the country to the sea. Not only does the

canal increase the number of factories but occasions the setting

up of many new ones in places where the land was of little value

and where there were few people. The means of sending goods by

water to the towns of Hull and Liverpool also helps the merchants,

by enabling them to export greater quantities of goods from those

parts which lie a long way from the sea."

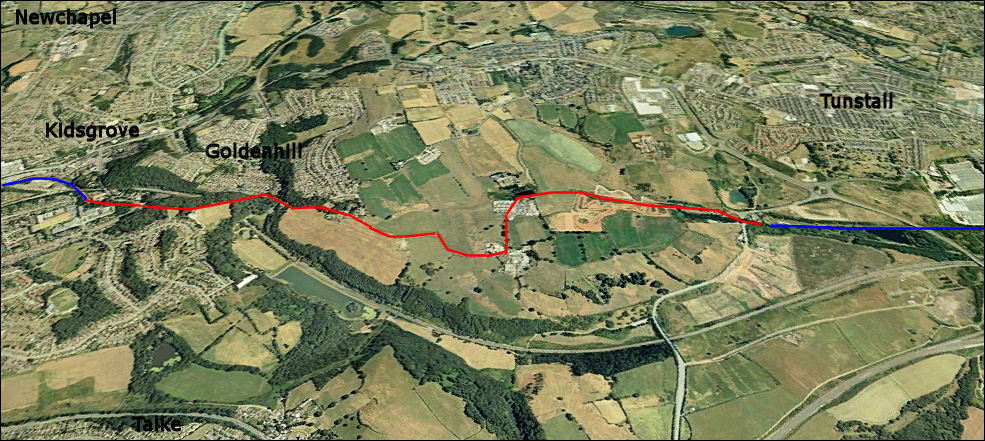

How Brindley planned the Harecastle

tunnel

1 He drew a plan and cross-section of the hill and worked out

where the tunnel was going to run.

2 The navvies started digging from either end of the tunnel

towards the middle.

3 Several vertical ventilation shafts were sunk into the hill

along the line of the tunnel.

4 Men were lowered down the shafts and then started tunnelling

out from them towards the other shafts and both ends of the

tunnel.

5 When the tunnel was completed, the shafts were left to

provide the bargees (men who worked on the canal barges) with

ventilation.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()