|

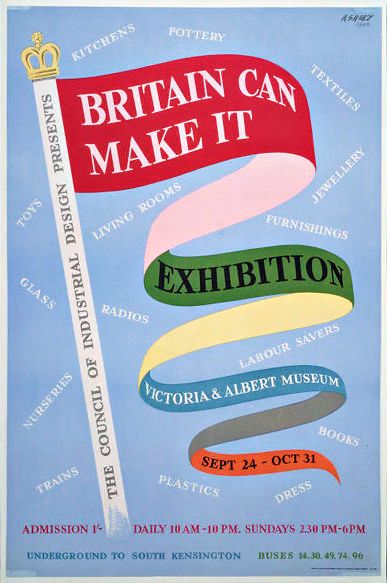

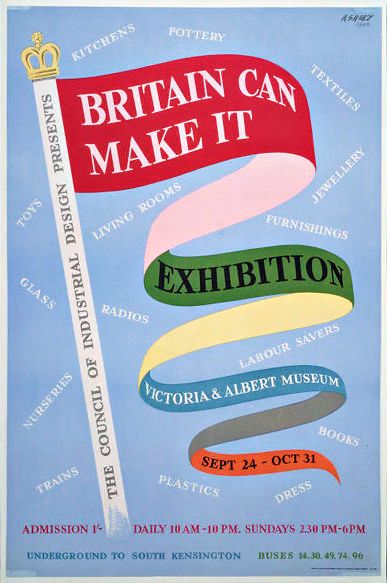

On 24 September

1946, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, His Majesty King George VI opened the first national exhibition of design since the war (Figure 5). People queued for hours, paying

1/- (5p) entrance fee. The closing date was not determined when it opened. It was to be

'on a date between October 31 and November 23, according

to attendance' [PGGTR, October 1946, p 655].

|

Figure 5.

Poster for the Britain Can Make It

exhibition, designed by

Ashley Haviden, 1946. |

|

The exhibition proved so popular, with both trade visitors from home and overseas and the general public, that its closing date was extended to the end of the year. Known as

Britain Can Make It it was

a government sponsored exhibition organised by the recently formed Council of Industrial Design.

"The aim of the exhibition... is to select the best of British-made consumer goods and to show that, in peace as well as

in war, the industries of this country can be supreme." [P&G

March 1946, p 33].

A committee of potters was appointed to assist the Council of Industrial Design in arranging for designs to be submitted

for selection to the exhibition. Miss Susie Cooper RDI and fourteen men made up the

committee.

Miss

Susie Cooper RDI, Messrs. Robert W. Baker, Norman Bishell, C. E.

Bullock, George Campbell,

S. H. Dodd, J. F. Gimson, A. Edward Gray, Leslie Irving, F. Shephard

Johnson, Walter Moorcroft,

A. Steele, F. T. Sudlow, C. Wiltshaw, H. Francis Wood, [P&G March

1946, p 34].

The final decision rested with the committee appointed by the Council of Industrial Design.

Mr

W. B. Honey, Keeper of the Department of Ceramics, Victoria and Albert

Museum;

Mr Howard Robertson FRIBA, designer of the the British Pavilion at the

New York World's Fair;

Miss E. M. MacDermott, pottery buyer Peter Jones Ltd;

and Mr Harry Trethowan, director of Heal's (Wholesale and Export) Ltd,

[PGGTR, June 1946, p 404].

The British Pottery

Manufacturers' Federation appointed a further committee to assist the ColD committee on matters

of production and marketing.

A.

Edward Gray, A. E. Gray & Co; Harry Steele, A. J. Wilkinson Ltd;

John Wedgwood, Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Ltd; and T. E. Wild, T. C.

Wild & Sons Ltd. [PGGTR, June 1946, p 404].

[Appendix 8]

In spite of the stated aims 'that the exhibition is primarily intended as a display for post-war designs'

[PGGTR, March 1946, p 159], it was inevitable that many pottery exhibits were designs from the 1930s or earlier, since new design had been in suspended

animation since at least 1942.

The manufacturing problems caused by lack

of raw materials, especially for decoration, shortage of labour

and problems of post-war reconstruction added to the difficulties. In the exhibits from those potters who were able

to

show their latest designs for the export market we have a foretaste of 1950s design

styles, [PGGTR, September 1946, pp

595-98; October 1946, pp 655-62].

The selection

committee praised potters:

"the variety of the ware from which they had to make a choice was a great tribute to the resilience of the

manufacturers and the industry as a whole." [PGGTR,

September 1946, p 591].

The pottery exhibit was shown prominently in the main hall, in

the 'Shop Window Street', with other consumer products. The exhibition was designed by James Gardner who tried

to show the pots

"suspended

in space [PGGTR, September 1946, p

591] - on glass shelves, suspended on wires against

a black backcloth, floodlit from above and below, the pottery gives a feast of colour and

form" [PGGTR, Ooctober 1946, p

655].

At the entrance/exit a curved display with 'awkward pieces' was used as

a funnel for visitors, [PGGTR,

September 1946, p 591]. Other pots were incorporated into displays

in the 'Rooms for To-day' section.

There were mixed reactions from the industry. Many people

felt that the exhibits did not represent the industry but rather the conditioned outlook of the selection panel. Mr Norman

Bishell of Doulton & Co. Ltd. encapsulated that view:

"Many of the designs are of a high standard, but they are not

representative of the industry... The selectors follow a narrow and

doctrinaire path, .... colourless; the cult of the unobtrusive." [P&G,

November 1946, p 18].

Others acknowledged that selective exhibitions would always disappoint someone. Reginald G. Haggar, the historian, summed up:

"While accepting in full the principle of selectiveness it must be said at once that it will never be possible to appoint a selection committee about the

personnel of which everyone is in agreement; nor will it be possible to hold a selective exhibition which will satisfy every taste."

[P&G, November 1946, p 23].

The editorial comment in Pottery and Glass September 1846 p17 had the flattering but double-edged words:

"the pottery section of the

Britain Can Make It Exhibition... should be regarded as a style and fashion show, for it is remarkably emphatic

in its preference for the modern idiom.

There can be no doubt that the pottery selected for the exhibition is handsome. The selectors can hardly be criticized for what they

have included. Nearly all exhibits are good examples of the potter's art - sound durable "bodies" and glazes, shapes that are

aesthetically pleasing and efficient in use, decorations both colourful and appropriate. But there

is considerable dissatisfaction among the

potters about the wares that have been left out."

Unfortunately the exhibition earned a nickname because of the restrictions which prevented so many consumer goods from

being sold in austerity Britain, Britain Can Make It but Britain Can't Have

It.

In 1948 the Royal Society of Arts collaborated with the Council of Industrial Design in the first exhibition of work by

Royal Designers for Industry, Design at Work. Two pottery designers were featured in the exhibition at the Royal Academy

in London - Miss Susie Cooper, the only Royal Designer for Industry exclusively for pottery design up to that date and Mr

Keith Murray. Keith Murray, an architect, had designed for Josiah Wedgwood &

Sons Limited, Etruria, Stevens and

Williams, glass makers of Brierley Hill and Mappin & Webb, London silversmiths, during the

1930s,

[P&G, July 1948 1946, p 630; November 1948 p 1014].

The home market was very bored by undecorated ware and MPs for the City of Stoke-on-Trent frequently placed Parliamentary questions asking for relief to be

given, [PGGTR, March 1949, p 264]. There was a

trickle of decorated ware available in the form of export rejects (Figure 6). These pots, considered unfit for export, could be

bought at home. The Board of Trade had strictures on retailers preventing anyone being able to assemble a complete service.

As might be expected, a black market thrived in Export Rejects and one of the leading potters, James Plant of R. H&S. L. Plant

of Longton, was Chairman of the committee established to combat it. [PGGTR,

September 1947, pp 719-23; May 1948 p 423; July 1948 p 624; August 1948

p 726].

The Editor of the Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade

Review made a perceptive comment when a slight easing in regulations on decorated ware for the home market was announced in May 1952:

"there is, of course, another class of people, who unlike the rest of us, regards the lifting of restrictions, not as the dawn of better times, but as a major tragedy. They are the black marketeers, the spivs, the secret

decorators of whiteware and the like who inflamed the legitimate traders by their shabby dealings. For such people this return to sanity means that their business

is at an end, [PGGTR, July 1952, p 1075].

|

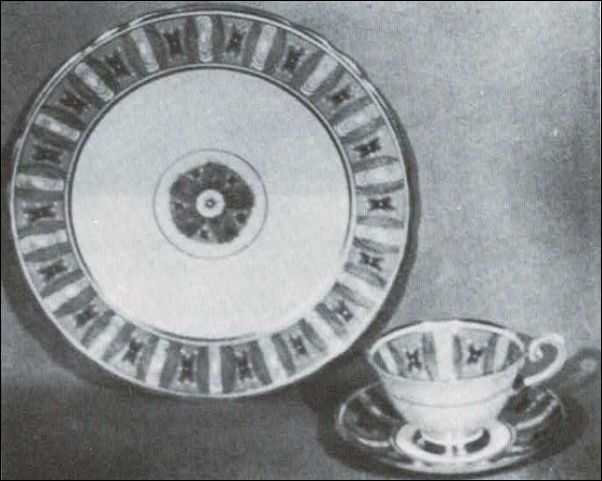

Figure 6 Plate,

earthenware, printed outline filled with enamel colours, Booths

Ltd., Tunstall. An Export Reject - given as a wedding present to

Mrs Molly Midworth, 1946, who gave it to Stoke-on-Trent City

Museum and Art Gallery. |

|

In the early 1950s a few Commonwealth countries imposed

import controls. The ware designated for these markets but unable to be sent were named Frustrated Exports. They were

released, in stages, for the home market, unexpectedly increasing the amount of coloured ware available to the British

buyer, [P&G June 1952, p 85]

A

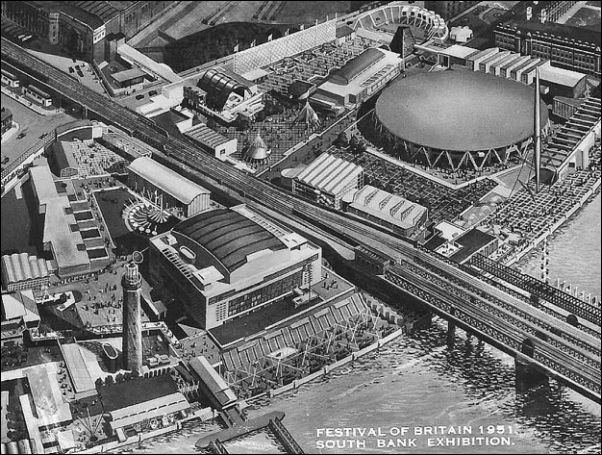

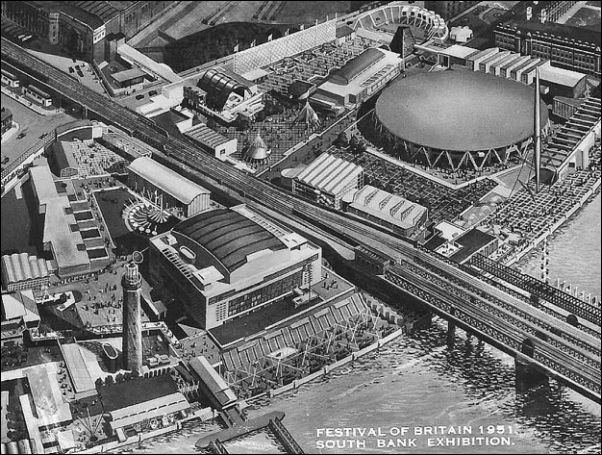

second major exhibition was planned as a means of

promoting British industry (Figure 7):

"The Festival of Great Britain, to be held in 1951, has been conceived

as an exhibition of the nation's contribution to modern civilisation in culture and the Arts, in Science and in Industry... the Festival is

intended to represent British manufacturers as a whole." [PGGTR

March 1949, p 243].

Figure 7 The Festival of Britain,

South Bank site, London, 1951 |

The Council of Industrial Design would select the exhibits from the '1951 Stock List'. Manufacturers were invited to send

leaflets, catalogues, samples of their best ware to be compiled into the list. New processes and materials could be notified,

confidentially, to the Council too. It was stated that only contemporary production and technique would be eligible, a

rule which caused much debate in the Potteries. It was argued that pottery design had withstood the test of time, over a

hundred years in some cases. It was hoped therefore that traditional design with modern interpretation would be

selected. Market places in the world expected tradition from the British potteries. In the same Pottery Gazette article we read:

"British pottery has a unique and world-wide reputation. It cannot be classed with radio cabinets, electric irons and the like, where there is

no tradition. When visitors from overseas pour into the exhibition, as everyone hopes they will, they will want to see British pottery,

traditional British pottery as well aa the modern designs." [PGGTR

March 1949, p 243]

The editorial in Pottery and Glass April 1949 p. 37 deplored the

ColD decision:

"The aim and object of the festival is to glorify British achievement.

Can it be to our benefit to hide away products which have proved themselves unbeatable over the years? The Council of Industrial

Design must think again here."

|

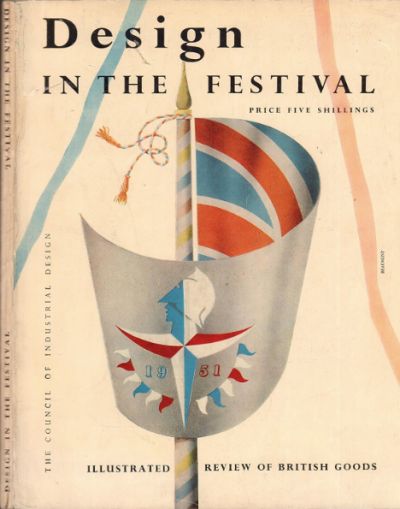

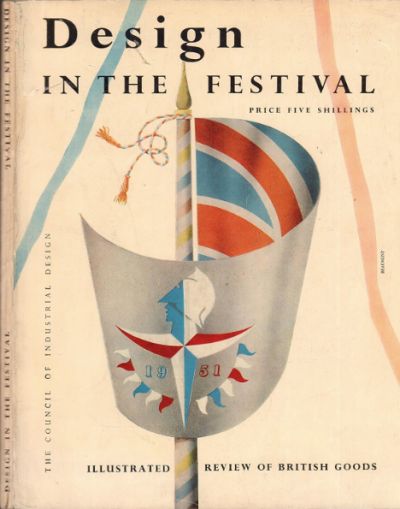

Figure 8 Cover of

booklet Design in the Festival, Incorporating Abram Games's

'Britannia' of 1948. |

|

There were no individual industry exhibits (Figure 8). Products were displayed throughout the Festival, particularly in the 'Lion

and Unicorn' and 'Homes and Gardens' pavilions but there was hardly any section of the Festival which did not have

examples of the potter's art:

China, earthenware and stoneware will be shown in the Exhibition

restaurants;

The Home section for domestic ware and fine china;

The British Idea section for fine china;

New Schools section;

Dome, generally for laboratory ware;

Seaside section for souvenirs;

Health section for hospital ware;

Natural resources section for china clay.

[P & G December 1949, p 51]

Design Review was naturally a centre for many ceramic designs. A spectacular display of pottery decorating was given in the

'Power and Production' pavilion throughout the Festival. The industry worked on a rota system, each team being present for two weeks, to demonstrate their techniques. An ingenious

display stand was devised with three work-benches for demonstrations (Figure 9).

If any bench was not in use the

section was turned round hiding the work bench with a display of

pottery. [P & G May 1951, p 51]. [Appendix 9]

Held in 1951 on the south bank of the river Thames, the Festival of Britain ushered in a new era in design. A conscious

decision to produce designs to a theme was initiated by the Council of Industrial Design after the Chief Industrial Officer,

Mr M. Hartland Thomas, attended a conference of the Society of Industrial Designers in May 1949. The speakers were

Professor Kathleen Lonsdale and Dr. Helen Megaw. Their subject was the 'structure of crystals'. A fascinating insight into

millions of nature's beautiful patterns. It was clear that designers in all decorative arts could be inspired by

crystallography, [PGGTR April 1951, p 576]

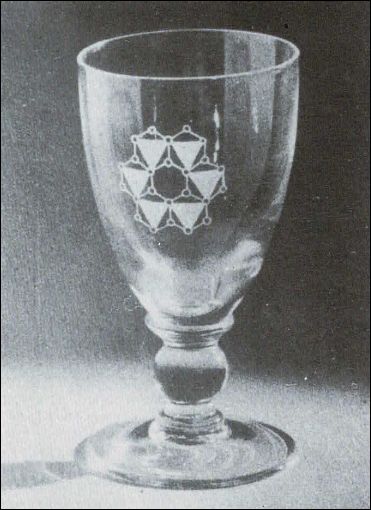

The ColD invited leading manufacturers from many disciplines to prepare patterns based on the crystal structure of

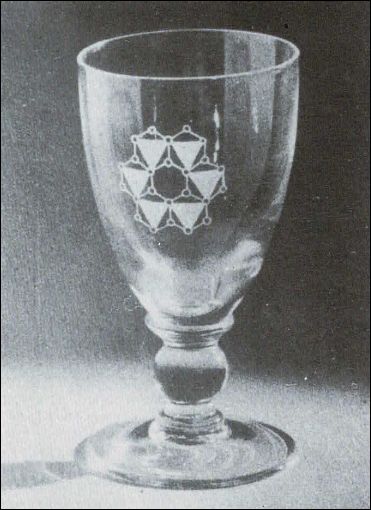

matter, for example china clay, sugar, haemoglobin, insulin and so the Festival Pattern Group was born (Figure 10).

|

Figure 10 Wine

glass with enamelled design inspired by the crystal structure of

china clay, designed by S W Tompson, made by Stevens and Williams,

Brierley Hill, Staffordshire,

Festival Pattern Group |

|

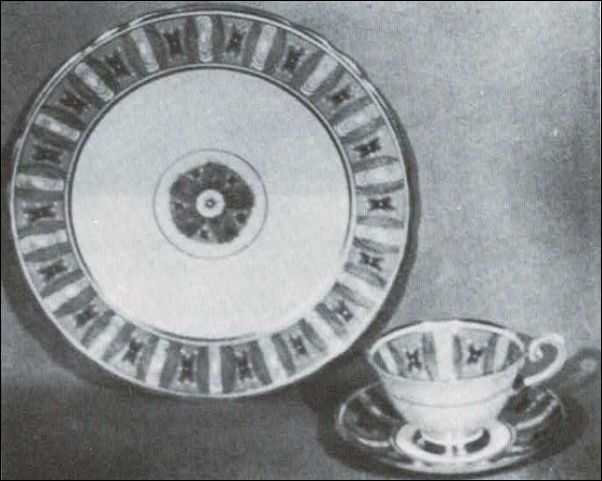

The

results of almost two years' work were promoted in the Regatta Restaurant of the Festival. Designers were enthusiastically

committed to the project by E Brain and Co. Ltd, Fenton; R. H. & S. L. Plant Ltd, Longton (Figure 11). and Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Ltd, Barlaston.

Figure 11 Tableware, Festival pattern,

bone china, printed overglaze, designed by Hazel Thumpstone, R H

& S L Plant Ltd., Longton, Festival Pattern Group. |

Preliminary work for pottery designs took

place at the Royal College of Art, London under the direction of Professor R. W. Baker. Away from the South Bank these

patterns were also shown in the Science Museum, South Kensington and in the Land Travelling Exhibition which visited

Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Nottingham, [PGGTR April 1951, p

577].

Pottery and Glass in May 1951 p. 74 described this

experiment and commented that

"The designs...are as representative of our age as the Canberra jet bomber. Yet they

are as old as Time itself."

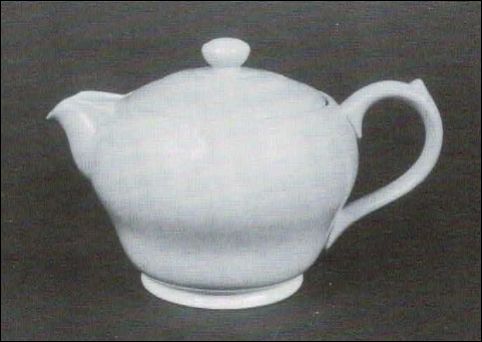

The production of decorated wares for display at the Festival continued the frustration felt in Britain

since there was still no indication of a date for the relaxation of utility regulations. In April and June 1952 W

T Copeland was

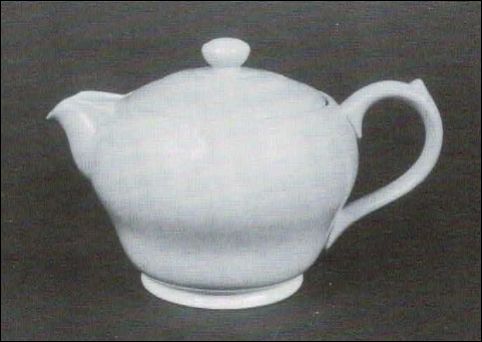

advertising Utility Ware teapots (Figures 12,13). [PGGTR April 1952, p

595; June 1952, p 937].

|

Figure 12 Utility

teapot and lid, green stained earthenware,

W T Copeland & Sons Ltd., Stoke-on-Trent.

Patented in 1941 and made until 1975. |

|

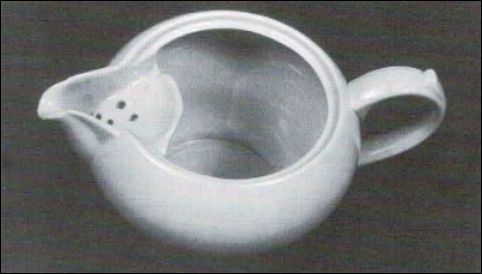

|

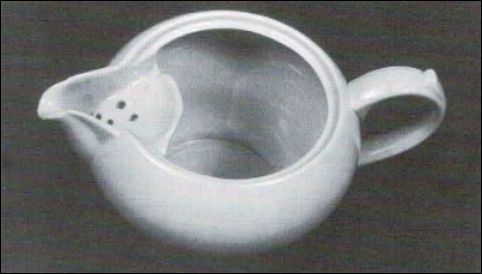

Figure 13 Same

teapot without lid to show the unique design which helped to

economise production costs. |

|

A Parliamentary answer from the President of the Board of Trade on 22 May

1952 was both encouraging and discouraging to the home market:

"In view of the recent decline in overseas markets I have decided to allow some decorated pottery to be sold on the home market during

the next six months, in addition to export rejects and frustrated exports...

The need for exports is such that I do not think it would be in the national interest to remove control altogether from the sale of decorated pottery in the home market." [PGGTR

June 1952, p 911]

The home market was therefore obliged to be content with a preponderance of plain wares, relieved from time to time with decorated items. Price control continued on most utility wares but in June 1952 all decorated pottery, white china, stoneware, jet and rockingham ware and some white earthenware were

released from price control, [PGGTR June 1952, p911].

Unexpectedly,

in August 1952, the President of the Board of Trade announced that

"all controls on the manufacture, have now been removed". [PGGTR

September 1952, p 1401]. At last the pottery industry was free to give priority to the needs of the home market. For over ten years

all design had been geared to the needs of export markets. The types of vessels needed did not suit eating here and the surface patterns were geared to foreign taste, which was often very traditional and staid. Modern design was not available from British potters and consequently people were looking

to Scandinavia, France or Germany for stylish pottery, [P & G

September 1952, p 58].

Potters in Stoke-on-Trent responded quickly to the release from the shackles of regulation. In February 1953 Roy Midwinter, of W R Midwinter of Burslem, was one of the first people to put new shapes and surface patterns on to the

market. [PGGTR February 1953, p 251]. With his excellent pattern designer Jessie Tait,

[PGGTR February 1953, 237, 253] Roy Midwinter led the way to recovery and stunning design for the next quarter century (Figure 14).

|

Figure 14 Teaware, earthenware,

handpainted underglaze, Primavera,

designed by Jessie Tait, 1954, on Midwinter's Stylecraft

shape, 1953

|

Kathy

Niblett

The author has asserted and given notice of her right under

section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

to be identified as the author of the foregoing article.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()