Pottery Index |

index of potters initials |

list of Stoke-on-Trent potters |

potters backstamps |

|

Ten Plain Years: The British Pottery Industry 1942-1952

Kathy Niblett

|

This article by Kathy Niblett appeared in the Journal of the Northern Ceramic Society, volume 12, 1995. The author has asserted and given notice of her right under section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this article. Reproduced here by kind permission of Kathy's husband Paul Niblett. Kathy was the Senior Assistant Keeper of Ceramics at Stoke-on-Trent City Museum and Art Gallery. References - PGGTR: The Pottery and Glass Trade Review; P & G: Pottery & Glass. The text is faithful to the original article, some reformatting has been carried out in an effort to make it more readable on screen |

![]()

next: National Design

Exhibitions

|

During the period

between the two world wars the

pottery industry in Britain produced three main types

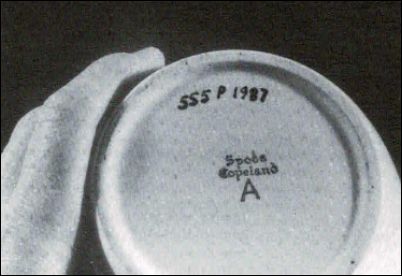

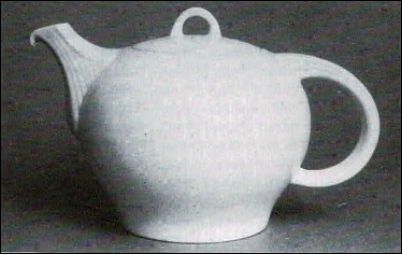

By 1942 the pottery industry had been obliged to change its emphasis. The home market was to be content with plain white or ivory coloured ware so that decorated ware could be sold abroad to earn foreign currency, especially US dollars, for the war effort (Figure 1). Decoration needs at least a third firing, often more. Decoration therefore needs greater investment from workers and in fuel. The added expense of decorated ware was a luxury which the country could not afford but which the country needed to use to its advantage in the market place

The industry was subjected to change in the form of concentration. Factories were closed to release people for war work in the Armed Forces or in munitions factories. Workers left in the potteries were amalgamated into the reduced number of works licensed by the Board of Trade to produce pots.

One of three things happened to pottery companies:

The Board of Trade controlled the pottery industry through-out the war and until all regulations were lifted in 1952. Pottery could only be made by those manufacturers licensed by the Board. Any infringement led to a court appearance and fines, [PGGTR, August 1944, p 446]. It dictated which items could be made, their quantity, price levels and by whom. At the onset of hostilities undecorated ware was freely available at home and decorated ware was allowed, on a quota system, but it soon became clear that there was such a grave shortage of useful wares, especially cups, that more stringent control was needed. On 18 June 1942 new regulations ushered in the age of plain utility for the home trade. Both bone china and earthenware with decoration were banned. The quota-free allowance of ware in coloured bodies and glazes or with edge line or band decorations was also stopped. Instead there was to be quota free, earthenware or bone china in plain white or ivory utility ware, stoneware in brown or the natural colour of the clay, in restricted shapes, [PGGTR, July 1942, p 409]:

The only exception was teapots and jugs in brown. All other items of domestic pottery and art pottery were banned from

manufacture.

The shortage of pottery could be attributed to the reduction in the number of workers available to make pots and in the increased demand for pots. It was estimated that about half of the 42,000 potters had been diverted to war work of one type or another. Sufficient crockery was needed for use at home, in industrial canteens, the British Restaurants, in hospitals and the Services.

These new, stricter controls had become necessary when it was obvious that regulations issued in December 1941 were not making the best use of the labour and materials available. The aim of the Board of Trade was to increase the supply of essential items to satisfy the replacement market and first-time buying of recently married persons. People were to be discouraged from buying more than they really needed.

Decorated pots for export were made continuously through-out the war but the extreme shortage of utility ware for home consumption forced the Board of Trade to implement a restriction policy. One method of meeting the crisis in 1942 was a temporary ban on the exportation of decorated ware to some colonies. The North American market was not affected, [PGGTR, June 1942, p 364]. A second method to curb export production was to cut the percentage of decorated ware produced, thus releasing capacity to make utility ware for the home market, [PGGTR, April 1942, p 252].

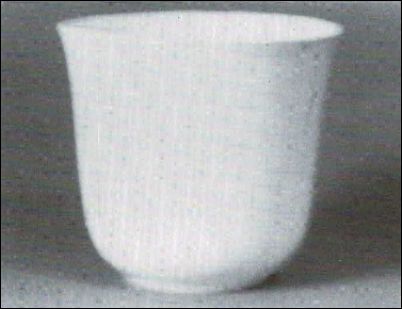

There was one scare throughout the industry in 1942 based on rumour and not on one of the many regulations of the Board of Trade. A daily newspaper set off the red herring of 'handleless cups' (Figure 4). It appeared that the Board had issued orders for all cups to be released without handles. This was a false premise based upon an urgent request from the Board that as many cups as possible be put on to the home market. A suggestion was made that surplus cups without handles also be released thus easing a serious shortage. These could then be used for cooler beverages, as in the case of beakers, and could also be utilised to serve several other purposes, such as that of a sugar bowl and a honey pot, [PGGTR, June 1942, p 364]. The Board of Trade assured Pottery Gazette that there was no intention to prevent handles being applied to cups so far as could be currently seen.

Lectures to the Pottery Managers Association encouraged the idea of future developments in all aspects of the

industry,

[PGGTR, April 1942, pp 241-243]. Designers maintained their freshness by meetings and lectures, planning for The Post-War

Home',

[PGGTR, April 1942, pp 233-39] and 'Planning for Prosperity,

[PGGTR, May 1944, p262-66] The famous art critic Herbert Read lectured on 'Industrial Design' in Stoke-on-Trent, at Burslem School of

Art,

[PGGTR, December 1943, pp 641-64]. The basic regulations remained in force, but after repeated rejected requests for decorated ware to be released for the home market, in August 1947 Sir Stafford Cripps, President of the Board of Trade, began to look at the idea of coloured bodies being used, [PGGTR, August 1947, p 652]. A

new order was issued reallocating potters to maximum price groups, changing the letters to be used in marking maximum prices and introducing three new groups.

Again some manufacturers were allocated within two groups according to product. [Appendix 7]

But optimism was also visible. A Working Party for the Potteries' was set up by Sir Stafford Cripps to discuss

reconstruction,

[PGGTR, October 1945, p 567]. It soon earned the name 'CRIPPS &

CROCKS',

[PGGTR, November 1945, pp 635-37]. Pottery owners took the chance to update their works. Several demolished their bottle ovens and replaced them with tunnel ovens, [PGGTR, November 1946, p 737]. Extensions were added incorporating the latest facilities..

By September 1947 31 electric kilns were in use [PGGTR, September 1947, p 738], and by November 1948 120 gas kilns in use in the 'smokeless Potteries', [PGGTR, November 1948, p 1012].

Facilities in workshops were improved, with additions like dust extractor fans, [PGGTR, August 1946, p 542]. Thus catching up with those potters who had pioneered enhanced factory conditions earlier in the century. In 1913 William Moorcroft had built a model factory in Cobridge and Wedgwood had the all electric Barlaston Works in use from 1940. Improvements in the decorating shop at the Royal Overhouse Pottery of Barratt's of Burslem included air conditioning, a dustless floor, good natural daylight and modern fluorescent lighting, [PGGTR, January 1948, p 48]. Several owners added new welfare provisions like works canteens. It was reported in June 1943 that at Crescent Potteries, Stoke-upon-Trent a new canteen had been opened. The walls had been painted with murals by artists, [PGGTR, June 1943, p 333]. Anew canteen was built at John Tams's Crown Pottery, Longton in 1947. The management believed that 'the comfort of the workers is of primary importance in the production of good pottery', [PGGTR, April 1947, p 326; June 1947 p 493]. In 1948 it was reported that T G. Green's Church Gresley Pottery near Burton-on-Trent had opened a new welfare block, [PGGTR, February 1948, p 142].

The fruits of this optimism were summed up by Gerald F. Wood of Arthur Wood and Son (Longport) Limited in a letter to the Editor of the Pottery Gazette

and Glass Trade Review in April 1952:

|

![]()

next: National Design

Exhibitions

Questions, Comments, Contributions? email: Steve Birks