thepotteries.org

thepotteries.org |

Ironstone - Stone Ware - Granite Ware

|

Ironstone is a type of stoneware introduced in England early in the 19th century by the North Staffordshire potters who were looking for a substitute for porcelain that could be mass-produced for the cheaper market. The result of their experiments was a dense, hard, durable stoneware that came to be known by several names e.g.: semi-porcelain, opaque porcelain, English porcelain, stone china, new stone -all of which were used to describe essentially the same product. There is no iron in ironstone - it was so named because of its durability. |

|

Earthenware

v Ironstone - The main difference between earthenware and

stone ware is that earthenware is porous and soft, while stoneware is non-porous, hard, and more durable. Stone ware is vitrified which makes it denser and less porous.

|

Mason & Co Patent Iron

Stone China fireplace

produced in 8 pieces - made in a

Cantonese style pattern

date: 1825-37

China Chimney Piece

Mason & Co. Patentees Staffordshire Potteries

Patent Iron Stone China

These Royal Arms are pre Queen

Victoria (1837)

- click for more -

Ironstone - key dates:

|

| Turner's Patent | Spode Stone China |

Mason's

Ironstone China Warranted |

|

|

|

|

It is recognised that John & William Turner produced the first vitrified stone ware. "The Turner's Patent ware can be of very fine quality and they can be regarded as the first of the British ironstone-type bodies" Godden, Ironstone, Stone & Granite Wares, p345 |

| There

were many 19thC North Staffordshire manufacturers of Ironstone

Various names were used such as 'Ironstone China'; 'Royal Patent Ironstone'; 'Ironstone', 'Royal Ironstone' -these usually didn't have any particular significance, each potter was often just trying to differentiate themselves from other manufacturers. Many marks incorporate the Royal

Arms - some potters had a Royal Warrant and were entitled to display

the arms. |

Ironstone China J & G Meakin - J & G Meakin - pre: 1890 |

Prince of Wales Royal Patent Ironstone Burgess & Goddard c. 1840s-90s |

J M & B Ironstone Indian Tree is the pattern name - John Meir & Son - c. 1837-90 |

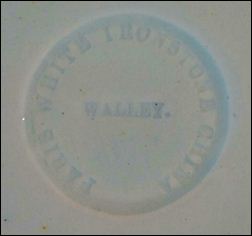

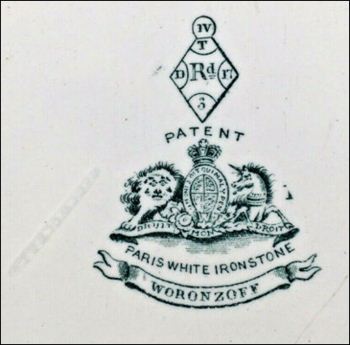

Examples of the use of the name 'Paris White Ironstone'

There was nothing special about

this type of ironstone - the potters

thought that a 'Parisian' connection sounded more sophisticated.

Walley Paris White Ironstone China (impressed) - Edward Walley - c. 1845-55 |

Paris White Ironstone Wedgwood & Co (impressed) The registration diamond gives a date for the registration of the pattern as 17the September 1867 - Wedgwood & Co - |

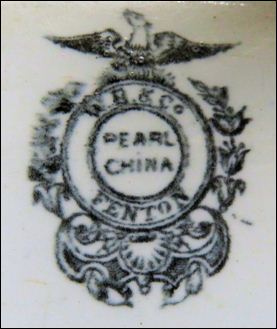

'Pearl China - Ironstone China'

W.B. & Co Pearl China Fenton |

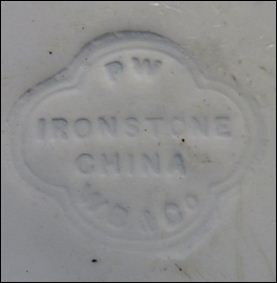

PW Ironstone China W B & Co |

|

c.1839-60 Both of these printed and impressed marks appear on the same platter. The ware was likely made for the American market (hence the eagle on the top of the printed mark) |

|

|

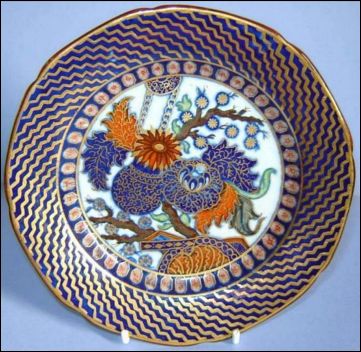

Decorated ironstone

The earliest ironstone items were decorated, many with hand painted oriental designs or transfer patterns in an attempt to copy Chinese porcelain cheaply. Although transfer ware was much less expensive than imported dinner ware, the dishes lacked the delicacy of the Chinese porcelain. Transfer designs covered the entire surface of each item to mask the flaws in the thick, heavy "stone china" beneath. |

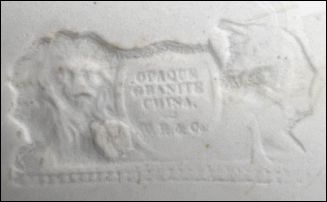

Opaque Granite China

W. R. & Co

William

Ridgway & Co mark

used on decorated ironstone ware

|

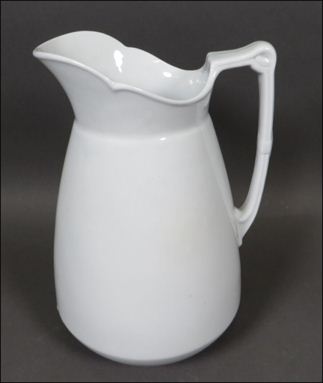

White ironstone china

In the 1840's, the English North Staffordshire potters began exporting the undecorated wares to the American and Canadian markets. The English potters discovered that the "Colonies" preferred the unfussy plain and durable china. Development of patterns Because much English ironstone was exported to

the US, American names were often used for patterns, including Columbia, New

York, Virginia, Union, Potomac and Atlantic.

- John Meir & Son - Because items made of ironstone were thick and heavy, the shape of the dishes became important. In the 1840s, James Edwards, John Ridgway and the Mayer Brothers introduced all white, beautifully glazed dinner ware with angular shapes that deviated from the gentle curves that had been traditionally used. In 1844, John Ridgway & Co. patented a design called "Classic Gothic," a hexagonal shape with crown finials and scrolled arches. Other potteries offered variations on the "gothic" design during the 1840s. Classical and ribbed patterns remained popular between 1850 and 1880. In 1851, Thomas and Richard Boote introduced an octagon shape, combining sharply angled outlines with softly curved or oval handles. T.R. Boote also produced the "Sydenham" shape in 1853, similar to the "Octagon" design, but more ornate and detailed. Another pattern, "Square Ridged," featuring scallops and ridges, was produced by several manufacturers in the 1880s. "Hexagon Sunburst" combined hexagonal shapes with rounded designs on handles. "Iona," by Powell, Bishop and Stonier, featured scalloped ridges along the bottom of traditionally shaped dishes. Plant & leaves patterns As Americans moved west, many patterns were based on the plants that could be found on the prairies. Fruits, grains, nuts and pods were embossed ironstone dishes. Wheat, corn and oats were used to represent the plentiful crops in the midwestern US. A pattern called "Corn and Oats" used ears of corn for finials on lids. Arcs of wheat decorated "Arched Wheat" by the American potter R. Cochran & Co., and a similar design called "Wheat and Hops" was produced by several English manufacturers. Leaves were also popular during the 1850s, including oak, maple, grape and ivy. Raised vines trailed around borders and cups. Grape leaves and vines sheltered tiny, embossed bunches of grapes. Other fruits were used as well, including peaches, figs, plums, pears and berries. Flowers also decorated a lot of the mid-century ironstone. Lilies of the Valley, tulips, forget-me-nots and hyacinths were used individually and also combined with other flowers in patterns such as "Meadow Bouquet" by W. Baker and Co. and "Summer Garden" by George Jones. An example of a mark from a white ironstone dinner plate - this mark was designed for the American market - the use of the British Royal Arms had been substituted with the American eagle and the shield with stars & stripes.

Pearl

White Ironstone |

T & R Boote Sydenham pattern |

Wedgwood & Co |

Edward Pearson |

English white ironstone

Stone China marks:

|

mark found on large Willow pattern platter |

|

|

1807-22 |

1807-22 |

1807-22 |

|

1883-86 |

|

American ironstone china

Until the late 19th century, most dinnerware in the US was imported. Although clay was plentiful in several areas, most of it was used to make bricks, tiles and practical utensils such as jugs and crocks. However, in the 1870s and 1880s, several American potters began to make white "granite ware." Most of these dishes were utilitarian. Bowls, spittoons, pitchers and milk pans were manufactured in great quantities, along with a uniquely American item called the "Daily Bread" platter that had sheaves of wheat and, in some cases, embossed mottoes around the rims.

Because of its sturdiness, durability, and popularity in rural areas, it was sometimes labeled "thresher’s china" or "farmer’s china." Most of the ironstone produced in the US had simpler shapes than the English imports which were still preferred by Americans. In an attempt to sell more of their wares, most American potteries did not mark their wares, and some used marks that resembled the British Royal Arms.

American Potters start to use American symbols on their ware As the quality of American made pottery increased people became more confident in purchasing American ware there was a transition from the use of the British Royal Arms to the use of the American Eagle, the Arms of the State of New Jersey. |

Questions, comments, contributions? email: Steve Birks